This story was originally appeared in New York Focus, a nonprofit news publication investigating power in New York.

On a crisp evening last spring, nearly 100 people packed into an elementary school auditorium in the Hudson Valley town of Athens. They had shown up to weigh in on the future of the town’s largest taxpayer and recipient of one of the biggest property tax subsidies in New York: a natural gas power plant.

For two decades prior, the Athens Generating Plant had received tax breaks averaging roughly $25 million a year. But that deal was about to expire, and its owners argued that without the abatement, the plant might be forced to close. They were looking to renew.

While a few attendees supported the new tax agreement, most of the dozen-odd speakers asked an unelected local agency called the Greene County Industrial Development Authority, or IDA, to deny the power plant’s request. The proposed renewal was “a great deal for the IDA, a great deal for Athens Gen, and a lousy deal for the town of Athens, the Catskill school district, and Greene County,” Lee Palmateer, an Athens resident and lawyer, said at the meeting.

Four months later, the board of the Greene County IDA voted to extend the tax subsidy to 2043 — three years past the state’s deadline for a zero-emissions electric grid.

The case wasn’t an anomaly. Across the state, IDAs enter into payment-in-lieu-of-tax agreements, or pilots, with businesses, exempting the corporations from property taxes in exchange for a lower annual payment to the town, county, and school district and the promise of job creation. And these little-known local authorities are quietly shaping the economics of the energy transition, in some cases threatening to undermine the state’s climate goals.

According to a New York Focus analysis of state records, the Athens Generating Plant is one of more than 70 fossil fuel projects that has received tax breaks from IDAs over the past two decades. In a review of data submitted by IDAs to the state comptroller and the Authorities Budget Office, New York Focus found that the agencies granted over $1.1 billion in tax breaks to fossil fuel projects from 2010 to 2022, averaging close to $85 million per year. During that same period, IDAs awarded significantly less — just over $400 million — to renewable projects. Several of the state’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters, including Athens Generating, are among the top beneficiaries of these abatements.

In principle, New York wants to shut those emitters down. In 2019, the state passed the landmark Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, or CLCPA, mandating the state transition away from fossil fuels and make its energy grid emissions-free by 2040. But many IDA boards don’t consider the climate law in their decision-making, according to interviews with several agency heads. As Earl Wells III, a spokesperson for the Genesee County IDA, pointed out: “There is no current state policy that requires consideration of the CLCPA emission targets when applications for projects are considered” for tax breaks.

Around 30 fossil fuel deals are set to expire in the next decade, New York Focus found. If they’re renewed, localities will continue to subsidize fossil fuel projects while the state is trying to switch to renewables. As the expiration dates approach, New York’s clean energy mandates hang in the balance.

“Why would we use IDAs to give tax incentives to companies we don’t even think can be in business much longer?” asked state Senator Liz Krueger, chair of her chamber’s finance committee. “Isn’t this sort of ass-backwards?”

Assemblymember Al Stirpe, the new chair of the economic development committee, told New York Focus that IDA subsidies for fossil fuel projects are a “really, really bad idea.” He worried that state and local leaders are at odds over climate goals: “If we’ve got one level [of government] fighting the other level, that drags out the transition to renewables.”

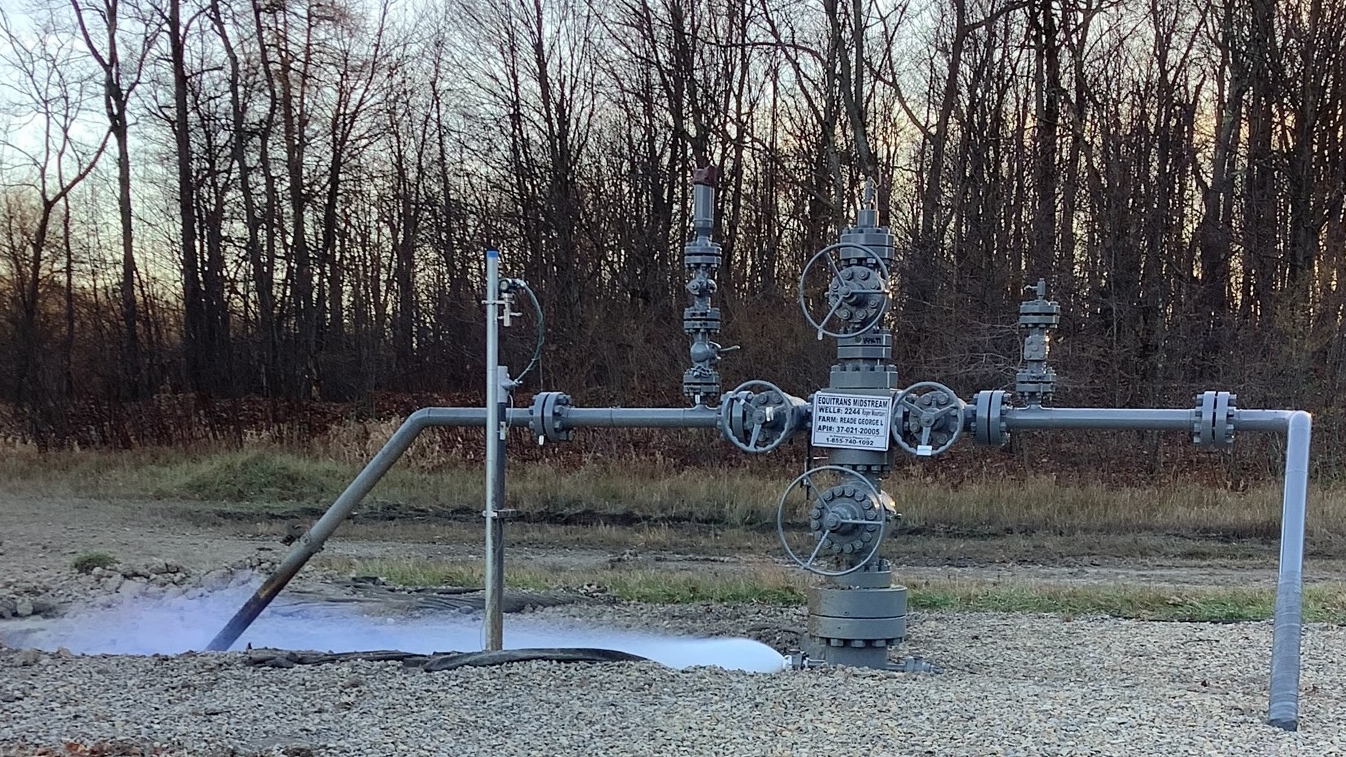

The lion’s share of the fossil fuel deals were negotiated in the early 2000s, as New York was phasing out its remaining coal plants in favor of gas. The Athens plant, completed in 2004, was part of a wave of new gas plants and pipelines built across the state, from the Buffalo area to Long Island. Many of them sought backing from local IDAs and scored pilot agreements.

“At the time, these were considered climate friendly initiatives, developed with State backing,” Glenn Nealis, executive director of the Delaware County IDA, told New York Focus by email. Almost two decades ago, his IDA signed a deal with the Millennium Pipeline, which snakes from the Southern Tier to the edge of Westchester.

Not every IDA was willing to subsidize fossil fuel infrastructure, however. In 11 of the 16 counties through which the Millennium and connected Empire pipelines run, pilot agreements have saved the pipeline companies a combined $94 million since 2010, according to state data. But in the other five counties, the pipelines don’t have pilot deals, so they pay full property taxes.

According to watchdogs, the patchwork nature of IDA subsidies indicates they shouldn’t have been handed out in the first place, even beyond climate concerns. That’s because IDAs are supposed to lure corporations to their regions using tax breaks. But counties don’t need the deals to land fossil fuel projects, according to state Senator James Skoufis, because those projects are already boxed in by geographic constraints.

“Fossil fuel infrastructure and, in particular, power plants, should, as a general rule, never receive incentives because they fail the ‘but-for’ test — but for the incentive, the project would not materialize,” Skoufis, the legislature’s top IDA watchdog, told New York Focus.

IDA subsidies touch all parts of the energy economy, not just fossil fuels. As tax breaks to some big polluters begin to taper off, they are above all tied up in the transition to renewables. IDAs have added hundreds of wind and solar projects to their rosters over the last decade, ranging from major wind farms to small community solar projects. According to state data, the annual tax breaks doled out to renewables went from $16 million in 2010 to $92 million in 2022 — outpacing those granted to fossil fuels for the first time.

Some proponents argue pilots are necessary for standardizing variations in the tax code, which doesn’t include clear assessment guidelines for power plants. For instance, a plant may be assessed at such high value that its regular tax bill, and any potential tax breaks from a pilot, would be quite large. But some in the energy industry argue that assessment may not reflect the true value of the plant. Rather than fight over it, the company and local officials hash out a pilot deal that both sides consider fair.

The few plants that do pay regular taxes pay far more than those that have negotiated pilots. One plant owned by the Long Island Power Authority, for example, until recently paid eight times more than the nearby Caithness, a privately owned plant that secured a pilot deal with the local IDA. (LIPA has since reached settlements with local governments to reduce its tax bills, but they remain significantly higher than those for the Caithness plant.)

Now, many of the deals struck in the early days of the gas boom are beginning to expire. Millennium’s pilot agreements with several counties end this year, and the company told New York Focus it is not seeking to renew them. Some power plant subsidies — including those to the Albany-area Empire Generating and Long Island’s Caithness power plant — are also due to expire this decade, setting up a reckoning over the plants’ futures as the climate law’s deadlines tick ever closer.

In the wake of the climate law’s passage, two natural gas plants asked IDAs for financial relief that they said was necessary to stay in business. Both requests were granted, giving them a boost even after the state had committed to an ambitious timeline to switching to renewables.

One was the Athens plant. Citing the state’s timeline for phasing out gas plants, the Greene County IDA wrote that without a new pilot, “there is no guarantee that [New Athens Generating] will be one of the conventional power plants that survive until 2040.”

The other was the Empire Generating power plant in Rensselaer, which had just emerged from bankruptcy. In 2021, the company said the plant was no longer profitable, and would not stay in business without a reduction to its existing $2 million yearly pilot payments. The Rensselaer IDA capitulated and cut the plant’s annual payments almost in half, to $1.1 million a year.

Meanwhile, the owners of the Empire plant and the Cricket Valley gas plant in Dover, New York, were complaining to federal regulators that the state’s promotion of renewables was unfairly hurting natural gas. They didn’t mention the local subsidies the plants were receiving. A clean energy advocate eventually did.

“Both complainants’ facilities have received roughly $200 million in direct cash subsidies from state and local governments to construct and operate their facilities,” wrote Tyson Slocum, director of the Public Citizen’s Energy Program, in a filing, “negating whatever (dubious) claim they have that certain zero emission generation resources receive unfair subsidies.” (The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ultimately rejected Cricket Valley and Empire’s complaint.)

The episode, Slocum told New York Focus, revealed a wider problem. “There’s no central clearinghouse” tracking the subsidies, he said. “We need to start doing that, to get an idea of what role public incentives play in incentivizing dirty energy.”

Officials from IDAs that subsidize fossil fuel projects largely do not see it as their role to apply the state’s climate law.

When the Greene County IDA renewed the Athens plant’s tax deal, it published a statement discussing the law at some length, but primarily in terms of a “risk” to the plant’s future. Nevertheless, the IDA vouches that the plant will remain in operation three years past the state’s deadline for an emissions-free grid. As of publication, the director of the Greene County IDA had not provided a comment for this story.

Nealis, of the Delaware County IDA, said the agency was required to review projects according to the broader environmental permitting law, but said enforcement of the climate law rested with state officials. “The IDA has no role in the determination of how [climate law] mandates are imposed,” he said.

“In no way” is the climate law irrelevant, said Bill Fioravanti, CEO of the Orange County IDA. But the agency’s current board “would most likely not let the fact that a project depends upon fossil fuels get in the way of them supporting significant job creation, especially in our top priority industry sectors.”

Orange County has forfeited roughly $40 million in taxes to major fossil fuel projects since 2010, including two gas plants and the Millennium Pipeline. (The two gas plants created about 20 jobs each, an amount Fioravanti acknowledged is “nominal,” though he hoped increasing power generation could draw other, more labor-intensive businesses to the area.)

The subsidies have flown under the radar for both regulators and environmentalists. The Cricket Valley natural gas power plant, for instance, was constructed in 2017 over widespread opposition from environmental groups and local farmers. But when its owners went to the local IDA in search of a tax break, it was granted a large subsidy with little objection from the public.

Greg LeRoy, executive director of the subsidy watchdog group Good Jobs First, said the autonomy granted to IDAs ends up harming local economies, because local officials lack the resources to fully scrutinize the claims of major companies that might come into town, creating an “asymmetrical power dynamic.”

“State policy should not pit very small communities with very little capacity against really big companies with very sophisticated capacity to manipulate debates,” he said.

The legislature has made several attempts to reform IDAs over the years, most recently with a 2021 package of bills that banned local officials from working for IDAs and explicitly added renewable energy to the list of projects eligible for incentives, among other changes.

Last year, Skoufis led a Senate investigation that found IDAs were granting pilots to projects even when they failed the key “but-for” test, sacrificing millions in local tax revenue even when it was not necessary to lure jobs. He has since co-sponsored legislation to stop IDAs from granting abatements of school taxes to projects.

But some say more changes are needed, and energy projects could be in the crosshairs. “I’m hoping we are able to pass some legislation that allows the state to go ahead and overrule what some of the local IDAs may be doing,” Assemblymember Stirpe told New York Focus. “I think without that ability, we’ll never reach the goals we have by 2050.”

This story was produced with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.