This story was originally published by Canary Media.

The future of all-electric, high-efficiency, grid-interactive homes seems near at hand from the floor of the CES 2023 event in Las Vegas. The massive annual extravaganza has long been the showcase for high-tech consumer electronics, including the latest in “smart” home automation systems, energy controls, and electric appliances.

Take the home product lineup from global electric equipment and technology giant Schneider Electric, which includes batteries, EV chargers, hybrid inverters, and the latest iteration of its smart electrical panel. Much like similar smart panels from global competitors like Eaton or startups like Span, it allows homeowners to monitor and control electricity demands at the circuit level via smartphone app, switch between grid and battery power, and keep electrical loads under the limits of household wiring or utility grid service.

Individual Wi-Fi-connected “smart plugs” add even more discrete control. Schneider’s CES-award-winning app and energy disaggregation technology from Sense, a startup partner, can help analyze data and automate the actions of all these devices to reduce utility bills, keep homes powered during blackouts, or even sell home-generated and stored power back to utilities.

Products like these and others showcased at CES 2023 are the building blocks of the home of the future — that is, a home that efficiently heats, cools and powers itself using electricity instead of fossil fuels, whether that electricity is coming from the utility power grid or the solar panels on the roof. In this not-so-hypothetical home, that electricity can also be stored in batteries, charge up electric vehicles, and even be shared with neighbors across power grids energized by a fast-increasing share of solar, wind, and other zero-carbon resources.

“We’re still at a point where under 10 percent of homes in America have solar or storage or these advanced technologies,” said Jaser Faruq, Schneider’s senior vice president of innovation. But homebuilders, electrical contractors and even utilities are starting to see this home-by-home transformation as inevitable, he said.

It’s a transformation that can’t come soon enough. Burning fossil fuels in buildings accounts for roughly 10 percent of U.S. carbon emissions, according to think tank RMI, making the conversion to electric heating a primary target for decarbonizing homes. (Canary Media is an independent affiliate of RMI.)

Add in the fuel burned by people’s cars and the carbon-emitting electricity that can be supplanted by rooftop solar panels, and the figures for these carbon emissions impacts rise to more than a third of the country’s total, according to nonprofit electrification advocacy group Rewiring America.

This makes home electrification a vital tool in combating climate change. The good news is that the technology it will take to achieve this vision pretty much already exists, as evidenced by the CES show floor.

But the home of the future is still out of reach for far too many Americans, and changing that involves a lot more than displaying a bunch of fancy gadgets at CES. Today’s high-end price points — about $10,000 for the full Schneider Home line of equipment, according to Faruq — must be moderated through economies of scale, government incentives and private-sector financing structures to make it economically feasible for Americans from all walks of life. That includes those living in midpriced single-family houses; multifamily apartments and condominiums; those who own their homes and those who rent; and those living in the coldest and hottest climates.

The rollout of these technologies should also be accompanied by broader energy-efficiency audits and retrofits that reduce energy waste and help customers lower their utility bills. But as yet, the business of whole-home weatherization and efficiency retrofits isn’t fully aligned with the business of selling solar panels, EV chargers, smart appliances, and home control systems.

Finally, it’s vital that utilities be brought into the equation. The shift to electric heating and transportation will drive the biggest increase in electricity demand in generations, creating massive new strains on the grids that supply that power. EVs and electric heating and cooling could overload local grid circuits if they’re all turned on at the same time. They could also drive regionwide grid shortfalls during extreme weather events, or just on hot summer evenings and cold winter mornings — stresses that are already putting U.S. grids under threat today.

Building the grid infrastructure to handle these emerging demands will take decades and cost billions of dollars. But if electric homes can be rewarded for coordinating when and how they use electricity to relieve those stresses, that could remove a barrier to their rapid growth while also making them more cost-effective for more people.

Eventually, entire neighborhoods could connect to form the building blocks of self-balancing, self-supporting clean energy networks, sometimes referred to as virtual power plants for systems that interoperate with the grid when it’s up and running, or microgrids for systems that can keep themselves powered when the larger grid goes down.

But to arrive at this future, we’ll need to solve a lot of fundamental challenges first.

From high-tech dream home to the real-life, nitty-gritty details

To begin to understand how to make the home of the future more accessible, we need to look beyond the technology-laden convention halls of CES to places like, say, the home of retired higher-education administrator Cheryl Ajirotutu in the Dimond District neighborhood of Oakland, California.

Ever since California’s 2000–2001 energy crisis, “I knew I wanted to go green,” Ajirotutu said. The rooftop solar panels she installed on her 1920s-era two-bedroom home have cut her electric bills roughly in half, but she knew that she could do more to make her home more efficient and climate-friendly. She just wasn’t sure where to start.

Through her work at Oakland’s Cypress Mandela Training Center, where she volunteers as a financial literacy educator, Ajirotutu heard about a home-electrification program from East Bay Community Energy, a community energy provider serving Oakland residents, and BlocPower, a New York–based startup that specializes in efficiency and electrification retrofits in underserved communities.

Ajirotutu applied to the program last year, and her home was selected as one of 100 to receive support. The first step was a whole-home energy audit whose purpose was to reveal “what you needed and why you needed it,” she said — an experience that changed her understanding of energy consumption.

The energy audit led to a whole-home retrofit. Local contractors reinsulated her walls, floors and attic, put in double-paned windows, and switched out her fluorescent lighting for LEDs. They also replaced the fossil-gas-fueled furnace that blew hot air through a single floor vent in her living room with a ducted-air electric heat-pump system that has eliminated the cold spots throughout her house — “it makes a real difference,” she said.

All told, these improvements are expected to reduce the energy consumption of Ajirotutu’s home by an estimated 88 percent. Once she replaces her gas-fired water heater with a heat-pump model later this month, she’ll be able to stop using gas entirely, a big goal of hers.

All of this work came at no upfront cost. Instead, Ajirotutu will pay $310 per month, a rate that equates to a zero-interest loan for the cost of the project.

“It wouldn’t have happened without that support,” Ajirotutu said. She doesn’t have the spare cash to put down on a project of this scope, and she’s generally leery of home renovation offers that seem too good to be true.

“At the same time, there are these houses that are, for lack of a better word, in decay,” she said. “We need help. How do we get that help?”

“That’s the genius of what Mark is doing,” she said. “He makes it affordable.”

Mark Hall is CEO of Revalue.io, the Oakland-based energy-efficiency project developer working with BlocPower to develop and execute its East Bay projects with local and minority-owned contractors and workforce-development organizations. So far, the projects he’s developed have led to an average 40 percent reduction in home energy use, he said.

But Revalue.io’s customers and contractors have a lot to do before the heat pumps, smart electrical panels or energy management systems go in, Hall said. First off, “we encounter a significant amount of remediation work — cleaning out debris, taking care of asbestos, and moisture concerns,” he said. Some efficiency programs and tax credits don’t pay for this remediation, which can effectively bar homes from being able to access them.

Nor can Revalue.io count on its customers being able to access cash or credit to cover the cost of retrofits, Hall said. “Qualifying for traditional lending programs with credit scores and documentation — that’s a barrier for many folks,” he said. “BlocPower provides flexible financing for our projects. That’s how our partnership is structured.”

“Another issue is the contractor workforce,” he said. Revalue.io considers it part of its mission to connect local contractors and young people from the East Bay’s economically challenged neighborhoods to the training and customer flows that will enable them to thrive in the emerging home-electrification industry. “A lot of the contractors out there focus on a few things, not all of them, to deliver electrification. Others aren’t really recommending particular electrification equipment, or they’re out there doing gas systems.”

Home electrification theory versus reality

Contractors can be forgiven for being less than enthusiastic about the prospect of home electrification. It’s much simpler and cheaper — and thus more lucrative for contractors — to replace a broken gas-burning furnace with a similar model than to take on the cost and complexity of reconfiguring a home to use electric heat pumps.

Adding in remediation and whole-home efficiency only increases that cost and complexity. Pilot projects that BlocPower did in Oakland found that all-electric retrofits cost an average of $35,000 when electric heating, appliances, electrical panels, lighting, insulation, windows, plumbing, and ducting are taken into consideration. In its broader retrofit project with Repower.io, “some of the projects we put through, there was a 1 percent, 2 percent return” for BlocPower in terms of the revenue it was earning from the projects “just to make them pencil” out economically, Hall said.

And while heat pumps are three to four times as efficient in converting energy to heat as gas furnaces, the vagaries of gas versus electric utility rates may not allow this far greater efficiency to translate to lower costs. In fact, only two of the nine pilot renovations BlocPower did in Oakland led to lower overall costs for the occupants when factoring together their utility bills and monthly payments to pay off the expense of installation. The rest saw monthly costs increasing from $50 to $100 post renovations.

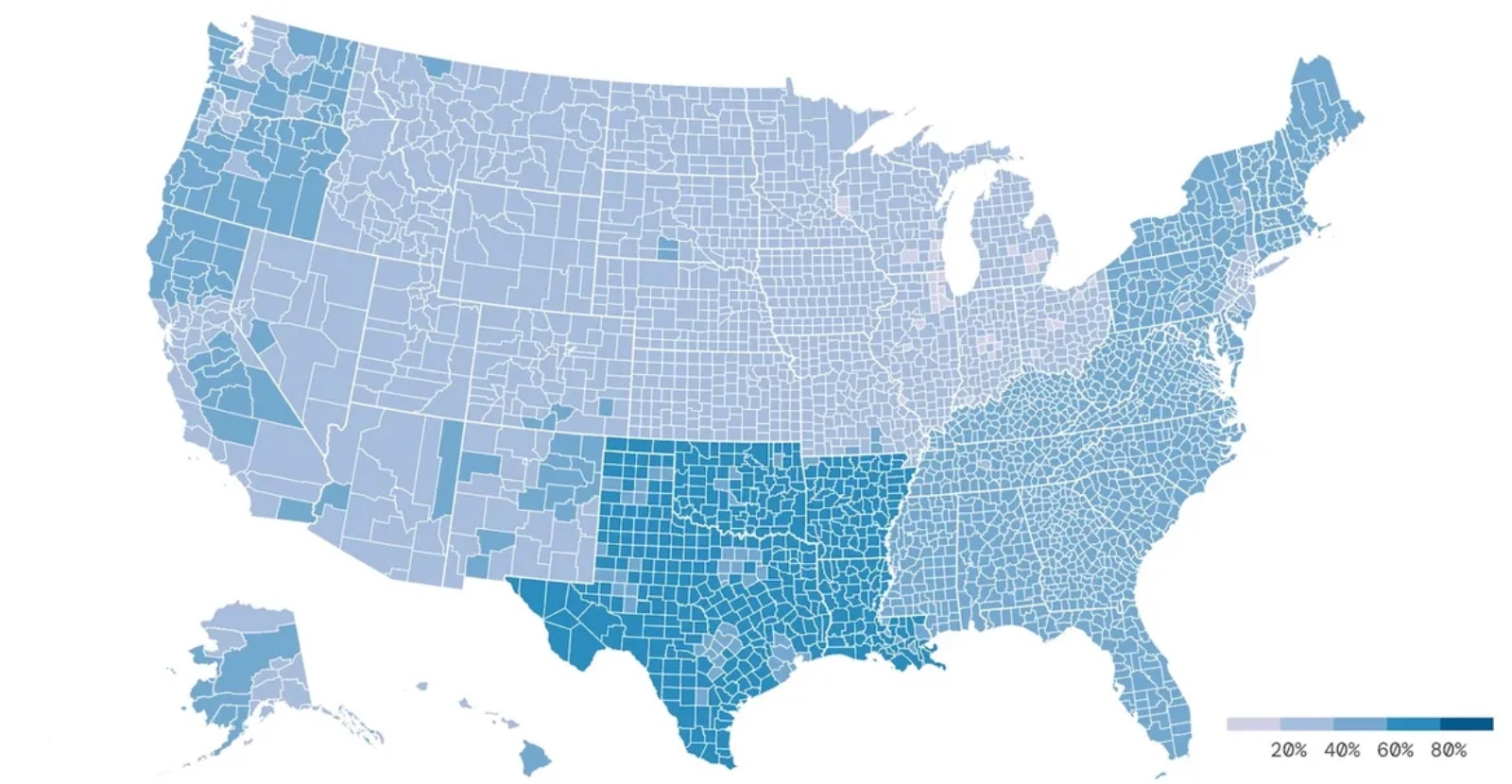

Results like these highlight the gap between the potential for widespread electrification and the real-world challenges in achieving it. Rewiring America estimates that 49 million U.S. homes — half of them low- and moderate-income households — can save significantly on their energy bills by going all-electric, primarily by replacing fossil-fueled or old-fashioned electric resistance heating with heat pumps for space and water heating. This map shows the percentage of homes that fall into this category by county across the country.

But there are about 131 million households in the U.S., which means about 80 million wouldn’t save money by opting for whole-home electrification. Those include homes where the costs of going electric are too high, or those in markets where electricity rates are higher than gas rates and so outweigh the greater efficiency offered by heat pumps.

Nor is electrification a slam-dunk for those nearly 50 million households that could hypothetically save money by going electric. Many of these homes may face costly and time-consuming electrical-panel or utility-grid service upgrades to add more electric loads than their wiring or grid connections were designed to handle. Contractors can struggle to obtain the equipment they need.

Connecting upfront costs with long-term benefits is even more complicated for the roughly 44 million U.S. households that rent rather than own their homes. In these residences, tenants tend to pay the bills but landlords bear the cost of upgrades. “The split incentive between tenants and property owners is a key issue,” Hall said.

Unless far more homeowners and tenants and landlords can see electrification making financial sense for them — and unless a whole lot more contractors and distributors and manufacturers see a clear path for that customer demand emerging — the home of the future won’t happen nearly fast enough to meet the need for combating climate change, he worries.

Getting government behind home electrification

The good news is that the policy tailwinds for home electrification have never been stronger. Last year’s Inflation Reduction Act will dramatically expand the federal government’s role in propelling this transformation. The law includes lucrative tax credits for home efficiency and electrification investments, from insulation and windows to heat pumps, solar, batteries, and EV chargers. It also directs about $9 billion in federal grants to state-level programs targeting lower-income customers for incentives that in ideal circumstances could cover almost the entire cost of the equipment involved.

But analysts agree that the impact of these federal tax credits and incentives will rely on effective state implementation. U.S. utilities are largely regulated by state entities, and building codes and mandates are carried out at the state or local government level. And the most significant federal rebates for home efficiency and electrification will rely on state energy agencies to be put into practice.

“I think there’s a lot of fantastic stuff in the [Inflation Reduction Act]. It’s a defibrillator to the heart of climatetech in America,” BlocPower CEO Donnel Baird said in an August interview. “The next wave is to go out to the states and persuade them on a state-by-state basis that you don’t need gas…it’s a terrible public health risk; it’s expensive for your utilities.”

Some of the policy, regulatory and commercial structures for making home electrification pay off are starting to emerge in states with the most ambitious climate agendas. Those include electrification-friendly building codes, building decarbonization mandates, and fossil-gas equipment bans; incentives for property owners and contractors to install more climate-friendly equipment and whole-home efficiency improvements; and utility rate plans and financing or repayment structures to bolster the cost-effectiveness of all-electric systems.

All of these federal, state and local policies still face an uphill battle to accelerate the pace of work needed to combat climate change, however. The most aggressive state-level electrification and decarbonization policies to date focus on new construction, not the more expensive and complicated task of retrofitting existing buildings.

As Sarah Baldwin, director of electrification policy for nonprofit think tank Energy Innovation, emphasized in a December presentation, the building sector “has an inherently slow stock turnover,” meaning that it takes decades for heating and cooling systems and appliances to wear out and need replacement.

To speed this up, “the building sector needs a more comprehensive approach to deal with underlying challenges to market transformation, financing mechanisms, revised utility regulatory approaches, expanded workforce training, and well-designed programs for consumers,” Baldwin said. In other words, just about every aspect of how efficiency and electrification programs and projects are administered and financed today needs an upgrade.

Getting the public on the home-electrification bandwagon

But even if all the right programs and policies to support electrification fall into place, it doesn’t necessarily mean Americans will instantly jump on board.

“We have 100 million homes to [upgrade], and each one of these homeowners has to be individually convinced that electrification or partial electrification is the right path for them,” Nate Adams, CEO of electrification software and training company HVAC 2.0, said. And while a small subset of homeowners is deciding to take on electrification on their own, most rely on contractors to tell them what their options are, he said.

Energy savings alone won’t do the trick, Adams contends. U.S. homes using oil, propane, or electric resistance heating can realize quick paybacks on heat pumps, he said. But gas-fired heating is still quite cheap in most of the country, meaning that heat pumps may have to operate for 10 to 20 years to pay back their upfront costs.

“That’s not going to sell a job,” Adams said. Instead, contractors must sell homeowners on the other benefits of electrification and heat pumps, such as improved control over household temperature and comfort that the latest inverter-equipped heat pumps can provide, he said. While some customers are motivated by environmental or health concerns, others may find those sales approaches a turnoff, he said.

Meeting consumers where they are, not where electrification advocates want them to be, is also important, Adams added. For example, contractors must be ready to offer cost-effective and suitable electric options for replacing furnaces and water heaters when they break down, which is when almost all homeowners are actually prepared to spend the money. But they also need to be ready to sell homeowners on broader energy audits that can determine the value of a more holistic and proactive approach to efficiency improvements.

That’s the goal of companies such as Elephant Energy, a Colorado-based startup that CEO D.R. Richardson describes as a “one-stop-shop for home electrification.” The company offers homeowners software-based assessments of retrofit costs and energy-saving potential, manages system design and contractor selection, helps them obtain the variety of federal, state, local and utility incentives available, and procures equipment on their behalf.

“We’re using capitalism to accelerate electrification. We’re taking on all the risk of design and equipment procurement,” Richardson said. There are about 200,000 HVAC and electrical contracting firms in the U.S., many of them smaller businesses that don’t have the capital or staff to keep up with changing state, local, and utility incentives or to place bulk orders for the latest heat pumps or smart electrical panels, he added.

Elephant Energy’s goal is to become the “Sunrun of home electrification,” Richardson said, name-checking the country’s biggest residential rooftop solar installer’s success in scaling up a business across more than 22 states and Puerto Rico. While Sunrun works with regional and local installers across the country, it has consolidated everything from home solar assessments to securitizing the leases and loans it arranges for its customers.

How to fund a rapid scale-up in investment?

Standardizing and consolidating the currently fractured commercial landscape for U.S. home energy efficiency and home electrification is a vital step in scaling up installations fast enough to make a dent in climate change. But right now, the level of finance required to do this is far less than what it needs to be.

BlocPower has raised more than $100 million to fund large-scale electrification retrofit projects in California, Colorado, Illinois, New York, and Wisconsin, including ambitious 100 percent building electrification efforts in Ithaca, New York and Menlo Park, California. Startups including Elephant Energy, Sealed and Service 1st Financial and solar lenders including Mosaic and GoodLeap are collectively raising hundreds of millions of dollars to expand the market for home electrification by connecting contractors with commercial lenders, rooftop solar installers, and electric-vehicle companies.

But Cullen Kasunic, BlocPower’s energy efficiency and renewable energy finance leader, told Canary Media that private-sector investment in home efficiency and electrification could be orders of magnitude higher. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that Americans spend about $100 billion per year on energy that’s wasted due to inefficiencies in building heating, cooling and insulation. The market for efficiency and electrification retrofits to combat that waste could add up to $500 billion, Kasunic estimated. Anuj Khanna, CEO of Service 1st Financial, estimated that the market for swapping electric appliances in for fossil-fueled furnaces and water heaters in U.S. homes could add up to $30 billion to $40 billion per year — and “this is only the replacement market.”

Most households will need to replace their old furnaces, water heaters, stoves and other fossil-fueled appliances at some point. The question for those who want to go electric is whether they can access the low-cost debt financing or other means to cover the higher upfront costs of the newest, all-electric models, rather than choosing the cheaper, dirtier options.

Khanna’s company has approached this challenge by developing a leasing program that shifts the upfront equipment and installation and long-term maintenance costs of this work from homeowners to contractors via banks and other lenders. That kind of structure has become common for home rooftop solar systems but has yet to grow to scale for home efficiency and electrification.

BlocPower has been able to offer customers no-upfront-cost installations in return for monthly payments via project financing commitments from Goldman Sachs and the Microsoft Climate Innovation Fund. Sealed has signed a credit facility with New York Green Bank to bring in public- and private-sector debt financing for its projects. Innovative public-private partnerships at the state and federal levels are aiming to expand the scale and scope of private debt financing for home efficiency and electrification and adding solar, batteries, and EVs to homes.

The combination of policy pressure and stronger economics are also encouraging electric-home-equipment manufacturers to invest in expanding production and distribution for U.S. markets. This equipment is coming in at price points meant to meet the needs of a variety of homes with a variety of incomes in a variety of climates, including colder climates where older generations of heat-pump technologies are being replaced by new technologies that can handle subfreezing temperatures with aplomb.

The technologies now on offer include 120-volt heat-pump water heaters that can plug into standard electrical outlets and window-mounted heat pumps from startups such as Gradient that can both heat and cool rooms in homes and apartments. BlocPower has inked deals to bring technologies to the U.S. that already have significant global market share, such as Fujitsu’s split terminal heat pumps to replace packaged terminal air conditioners. It has also partnered with up-and-coming innovations from startups such as Harvest Thermal, which makes heat pumps that heat both water and air and can store heat to ease demand on the electric grid.

Making electric homes grid-responsive

These kinds of grid-supporting features are the final component that needs to fall into place to make the home of the future a reality today. Multiple studies have shown that electrifying transportation and buildings, while a vital step in combatting climate change and a net economic positive in the long run, will also create new strains for utility grids that weren’t designed to handle them.

Finding ways to manage these new loads to ease those strains could convert those strains into supports. Both batteries and heat-pump water heaters can store up excess solar power to ride through post-sundown shortages, for example — one simply stores that power as electricity and the other stores it as extra hot water. EV chargers and clothes dryers can both be scheduled to avoid using grid power when it’s scarce and to kick in when that power is plentiful.

These “virtual power plants,” made up of tens of thousands of homes orchestrating their equipment to serve the grid, could convert kilowatts of energy-shifting values per home into megawatts of utility-program and energy-market value, and return fractions of that value back to individual homeowners to reduce the cost of electrification.

“We think that’s an amazing opportunity: virtual power plants with heat pumps and rooftop solar,” BlocPower CEO Baird said.

So does Jigar Shah, head of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office, which has hundreds of billions of dollars of federal lending authority to boost deployments of clean energy technologies. One of Shah’s goals is to back business models that make smart appliances, solar-plus-battery systems, and other grid-responsive assets more affordable and accessible for a broader range of Americans.

“Consumers have all these assets they’ve already paid for,” Shah said in an interview last month. Smart thermostats, heat-pump water heaters, refrigerators, washing machines and dryers, EV chargers, and other electric appliances represent gigawatts of grid demand being installed in U.S. homes on a monthly basis.

But as of today, the vast majority “aren’t subscribed into helping to provide grid services,” he said. That’s at a time when grids are under increasing stress from extreme weather and undergoing a shift from relying on round-the-clock fossil-fueled generators to variable solar and wind power.

Bundling a commitment from homeowners to make their newly installed appliances and devices available for grid services in exchange for lower upfront costs or ongoing revenue opportunities could solve consumer-affordability and grid-reliability problems at the same time, he said.

Grid services could provide a vital revenue stream for BlocPower’s mission, Baird said. In testimony before the U.S. Senate in 2021, Baird described how his family, growing up in a Brooklyn apartment without heat, were forced to use their gas oven at night to keep warm while keeping the windows open to let out the harmful fumes it emitted.

The shift to all-electric heating could allow communities like those he grew up in to “leapfrog gas, and gas pipelines and gas heating and gas hot water,” he said. “In the Bronx, there are 5,000 apartment buildings that still burn oil,” and 10,000 across New York City, he said. “We’ll move those directly to 100 percent clean electricity.”

Conversely, failing to make the all-in joint public- and private-sector effort to make home electrification a priority could lock homes into a carbon-emitting, air-polluting and increasingly costly status quo.

“In Colorado, gas prices are up more than double over the past two years,” Elephant Energy’s Richardson said. “Heat pumps are a hell of a lot more cost-effective.” But “if you miss your window and you replace your gas furnace with another one, you’re locking in your emissions for 10 to 20 years” — and that’s time the country doesn’t have to make the cuts in greenhouse gas emissions that it needs to make.