Eleven years ago, a human rights violation complaint arrived at the Business and Human Rights Resources Centre, or BHRRC. The London-based nonprofit monitors the activities of more than 10,000 companies around the world, and receives complaints about abuses every day. But this one was different: For the first time, the grievance involved a renewable energy project. Soon after, similar complaints began trickling in year after year. They warned that solar, wind, and hydroelectric companies were taking over land, restricting access to water, violating Indigenous people’s rights to prior and informed consent, and denying decent wages for workers.

Between 2010 and 2021, the center received more than 200 allegations of human rights violations linked to the renewable energy sector. “It became concerning,” said Mark Hays, a senior consultant at BHRRC.

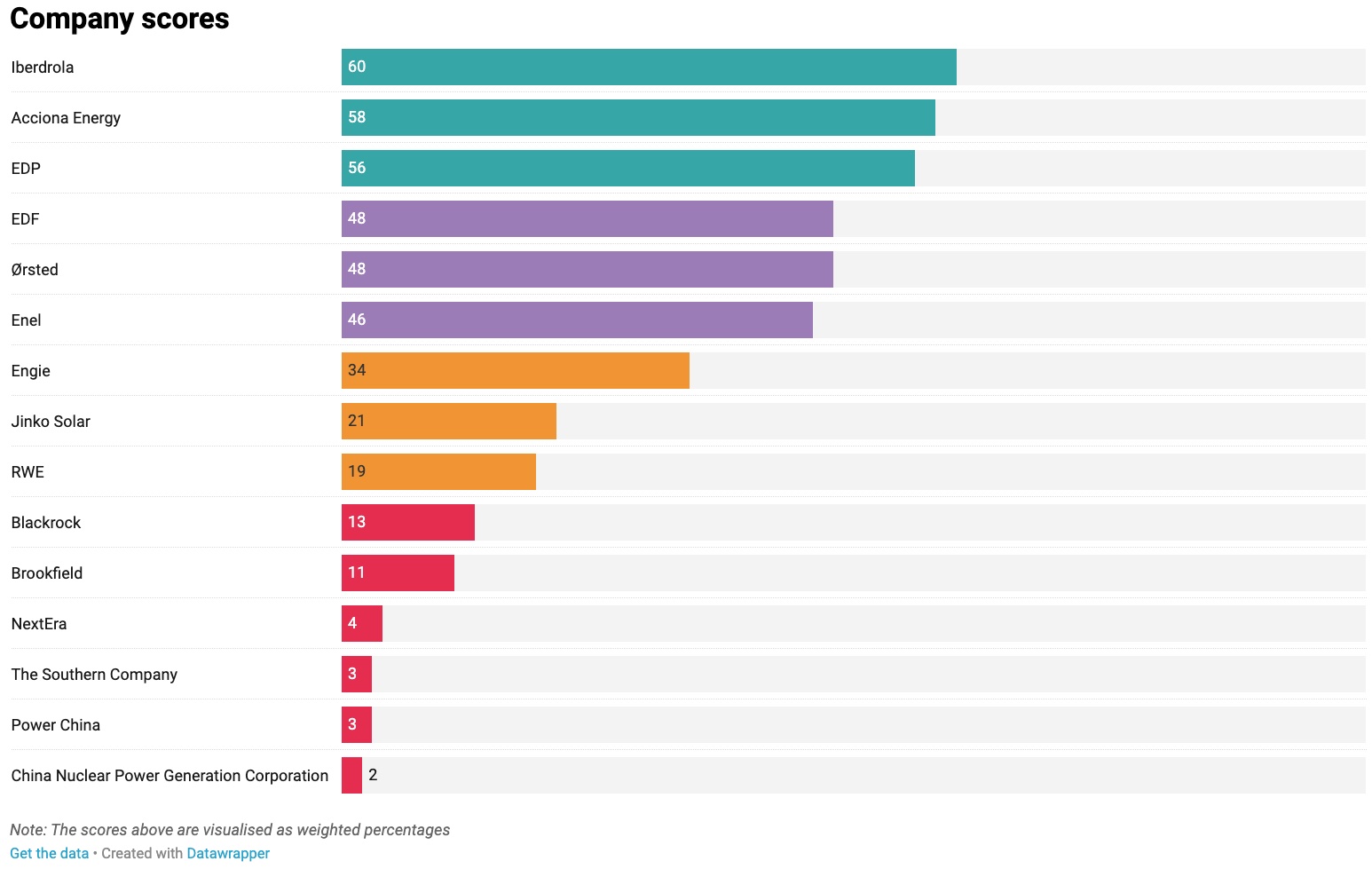

Last year, Hays and his colleagues established a way to analyze and score the “human rights policies and practices” of 15 of the world’s biggest renewable energy companies. They found that on average, the companies scored just 22 percent for their human rights practices across their supply chains. Last week, the group released its second analysis, saying the findings “should set off alarm bells.”

Although there was a slight increase in the average score to 28 percent, that number still “implies major human rights risks for communities and workers,” the report says. “Abusive business models, and the loss of trust they generate, put at risk the much-needed energy transition our futures depend on.”

The abuses include land rights disputes in places like Chile and Ethiopia, and the killings of several Indigenous activists opposing a hydroelectric power plant in Guatemala. Other examples include the violation of the right to prior and informed consultation with Indigenous communities in Kenya, Mexico, and Morocco, among others; legal harassment against wind turbine opponents in Taiwan; and reports of underpaid migrant employees in offshore wind farms in Scotland.

“It’s a very interesting report, timely and relevant,” said Susana Batel, a researcher studying social justice issues in the energy transition at Lisbon University.

Researchers at the Business and Human Rights Resources Centre asked three basic questions: Do these companies explicitly recognize they have to respect human rights? Do they try to address potential conflicts before they happen? Do communities have mechanisms to be heard by the company — and will they receive relief in case a violation occurs?

Seven out of 15 companies scored more than 50 percent for their human rights policies, and eleven improved their performance compared to the first report. Iberdrola, the second-largest wind energy company globally, along with hydro, biomass, solar, and thermal energy producer Acciona Energy and Portugal-based utility company EDP, scored more than 80 percent in these basic indicators. NextEra, the world’s largest wind and solar energy company, state-owned Power China, and Georgia-based utilities company The Southern Company scored the lowest –all of them with less than 5 percent.

“[After the first report,] we heard positive remarks from some companies saying, this is actually helping us make the case internally for a stronger set of policies,” Hays said. “It’s clear by how they’ve altered their policies, they’ve really taken to heart some of the key guidance.”

Beyond these basic indicators, however, scores plummeted across the board. Researchers dug deeper, looking at factors that imagine “what a just renewable sector that fully embraces and realizes human rights could and should look like,” Hays said. They include labor rights of workers mining rare minerals and building the technologies in factories, the land rights of those impacted by the projects and its supply chain, the rights of environmental defenders living in the projects’ areas, the waste solar panels and turbines will generate once decommissioned. It also includes issues like the transition to net-zero carbon emissions of the companies themselves.

The analysis found that none of the 15 largest renewable energy companies have a formal policy acknowledging the rights of human rights and environmental defenders. This is particularly concerning at a time when attacks against environmental defenders have reached record-high numbers, Hays said.

The lack of land rights recognition is also distressing, he said. None of the companies have policies in place that explicitly address how they will respect land rights, and only five companies partially complied with fair relocation policies. Similarly concerning, the report points out, is the lack of acknowledgment of Indigenous people’s rights to consultation when these projects occur in their lands. Conflicts around these issues have been widely reported in Mexico’s Tehuantepec Isthmus and Colombia’s Wayúu Indigenous reservation, among other sites.

It might be tempting to compare these companies’ impacts with those of the fossil fuel industry. Even if gas, oil, and coal rate significantly worse in similar, yet not as comprehensive, evaluations of basic human rights policies, Hays advises against it. “Comparing sectors is tricky because the impact of a coal mine on waterfalls or on the atmosphere is different from the impact of a wind farm or a solar array,” he said. “But if you’re an Indigenous community that has been displaced from your lands, if it’s a coal mine or a solar farm, the end result is the same: you are displaced.”

The similarities between human rights violations between fossil fuel companies and renewables are not new for researchers in this area, Batel, of Lisbon University, said. “The key problem is that the renewable energy transition is being performed in the same model that caused the climate crisis,” one that links infinite economic growth and production of goods to progress, the researcher explained. “For [the model] to exist, we have to continue to exploit places and a lot of communities and ecosystems.”

Getting out of that model will mean an economy that stops prioritizing growth and consumption and refocuses on human wellbeing instead, said postdoctoral researcher Alexander Dunlap, at the Center for Development in the Environment at the University of Oslo. Other possible avenues, Dunlap said, include energy autonomy for communities everywhere and a say in the decision-making process of these projects. Others advocate socializing wind, so the benefits of the energy transition will reach everyone.

“We have to keep in mind that the renewable energy transition is creating and reproducing injustices,” Bates said. Focusing on “changing the technology and energy sources will not bring a just transition.”