This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

As 2021 drew to a close, rain and snow pummeled California, raising hopes that the state’s ongoing drought would be alleviated. But the tap dried up in January, and historically low precipitation followed. Now, as summer approaches, it’s clear that those few months of reprieve did little to shore up the state’s water reserves, and analysts are warning that the state’s hydroelectric supplies — a cheap source of clean power in California — are once again at risk.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration, or EIA, reported last week that as reservoir levels dip far below their historic averages, electricity generation from California’s hydroelectric dams could be cut in half this summer. The shortfall is likely to be made up in part by an increase in natural gas-fired power, EIA said, sending more carbon dioxide and pollution into the air and pushing up summer electricity prices in the state.

“There is a growing recognition that hydropower may not be the reliable resource that it has been historically,” said Mike O’Boyle, director of electricity policy at the think tank Energy Innovation.

In 2019, prior to the current drought, 19 percent of in-state electricity generation came from hydroelectric dams, according to data from the California Energy Commission. In 2020, hydro dropped to just over 11 percent of the in-state power mix due to the effects of heat and drought. Now, EIA predicts that number could drop to just 8 percent this summer.

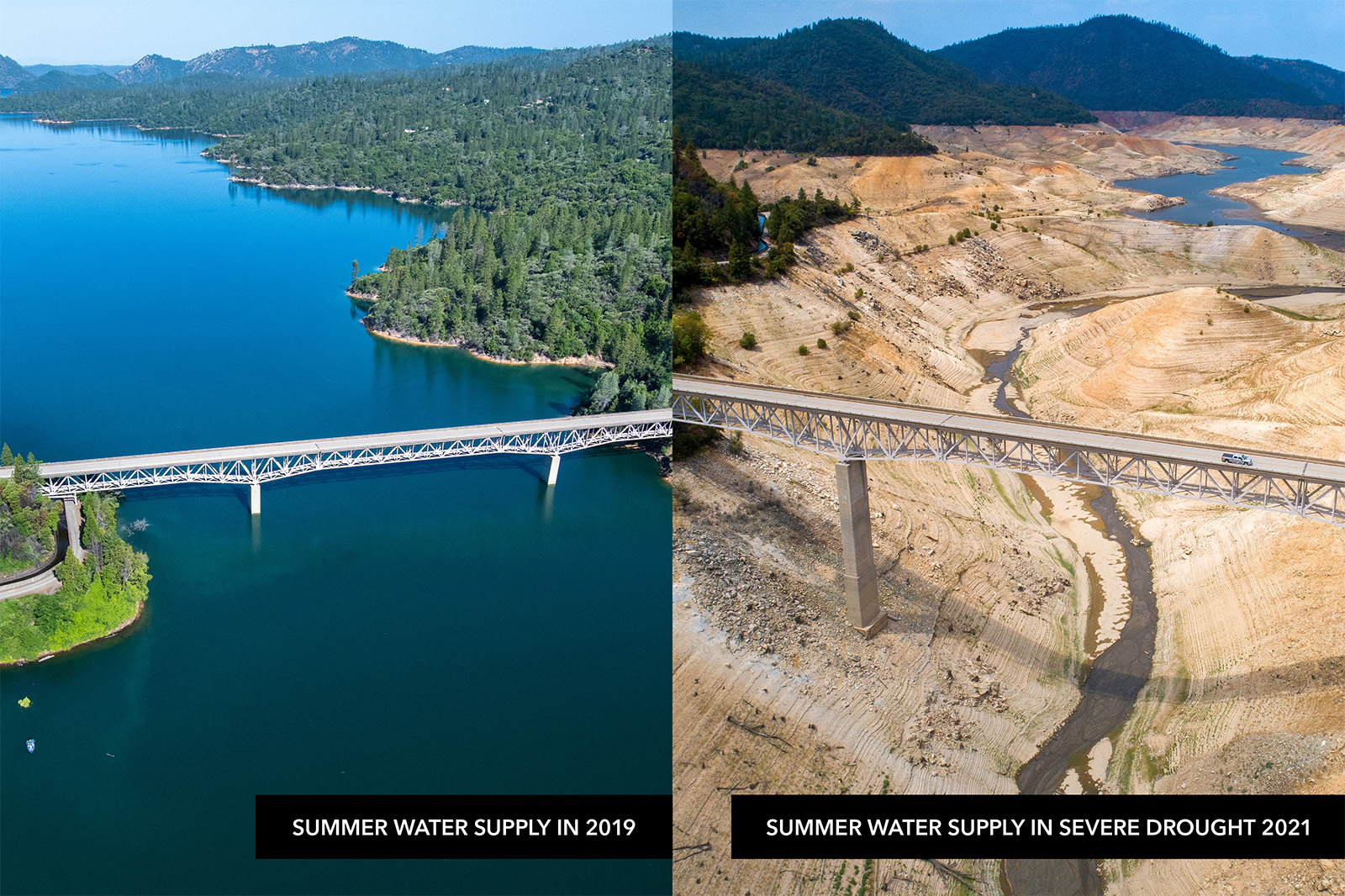

Hydropower plants are typically a crucial source of clean, “dispatchable” energy for the grid. Dam operators can ramp up or down electricity production by releasing more water to meet the grid’s needs as wind and solar output varies. But with reservoirs low, this flexibility will likely be compromised, EIA writes. The state’s two largest reservoirs, Lake Shasta and Lake Oroville, are at 48 percent and 67 percent of their historical average, respectively. As of April 1, snowpack throughout the state was just a third to half of normal levels, meaning there will be less melting snow to recharge already depleted reservoirs.

To make up for the shortfall, California’s grid operators will purchase more out-of-state power, but they will also turn to one of the only other sources of dispatchable power at their disposal: natural gas power plants. The EIA predicts that natural gas will rise to 50 percent of in-state generation this summer, increasing carbon dioxide emissions by 978,000 metric tons, or the equivalent of putting about 211,000 more cars on the road for a year.

In addition to the environmental and public health consequences, this switch to natural gas will also be felt by Californians’ wallets. The study finds that wholesale electricity prices — the price that utilities pay for power — could increase by 7 percent in Northern California and 5 percent in Southern California.

The shrinking prospects for hydropower on a warming planet is something California will need to contend with as it forges a path to 100 percent clean electricity by 2045. California Energy Commission staff told Grist in an email that currently, the state uses the 15-year historic average of hydroelectric availability in its models — a metric that may not capture the challenge that lies ahead. But they are “expecting to run more scenarios to capture potential impacts of droughts in long term planning.”

Michael Colvin, an expert on California energy policy at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, told Grist that in the long run, hydropower shortfalls could lead the state to delay the retirement of some existing natural gas plants, though it’s unlikely to build new ones. “When you look at what the load-serving entities are buying, they are almost all utility scale solar and storage (or just stand alone storage) contracts,” he said in an email.

That trend of relying so heavily on solar and storage is slightly worrisome to O’Boyle of Energy Innovation. The organization recently analyzed how California could achieve 85 percent renewable energy by 2030 without compromising reliability. The study found that even in a scenario with low hydropower, California can build enough renewable energy supplies to hit 85 percent, meet demand, and maintain reliability – but that diversification of energy sources was key. He said California should be investing more in offshore wind, geothermal, and other measures that reduce strain on the grid.

“If for some reason, solar is unavailable from cloud cover from wildfire smoke — that was an issue a few years ago — then a more diverse set of resources can perform better under those extreme conditions,” O’Boyle said.