As Grist unveils a new look and updated mission, we are checking in with notable figures working for a more just and sustainable future.

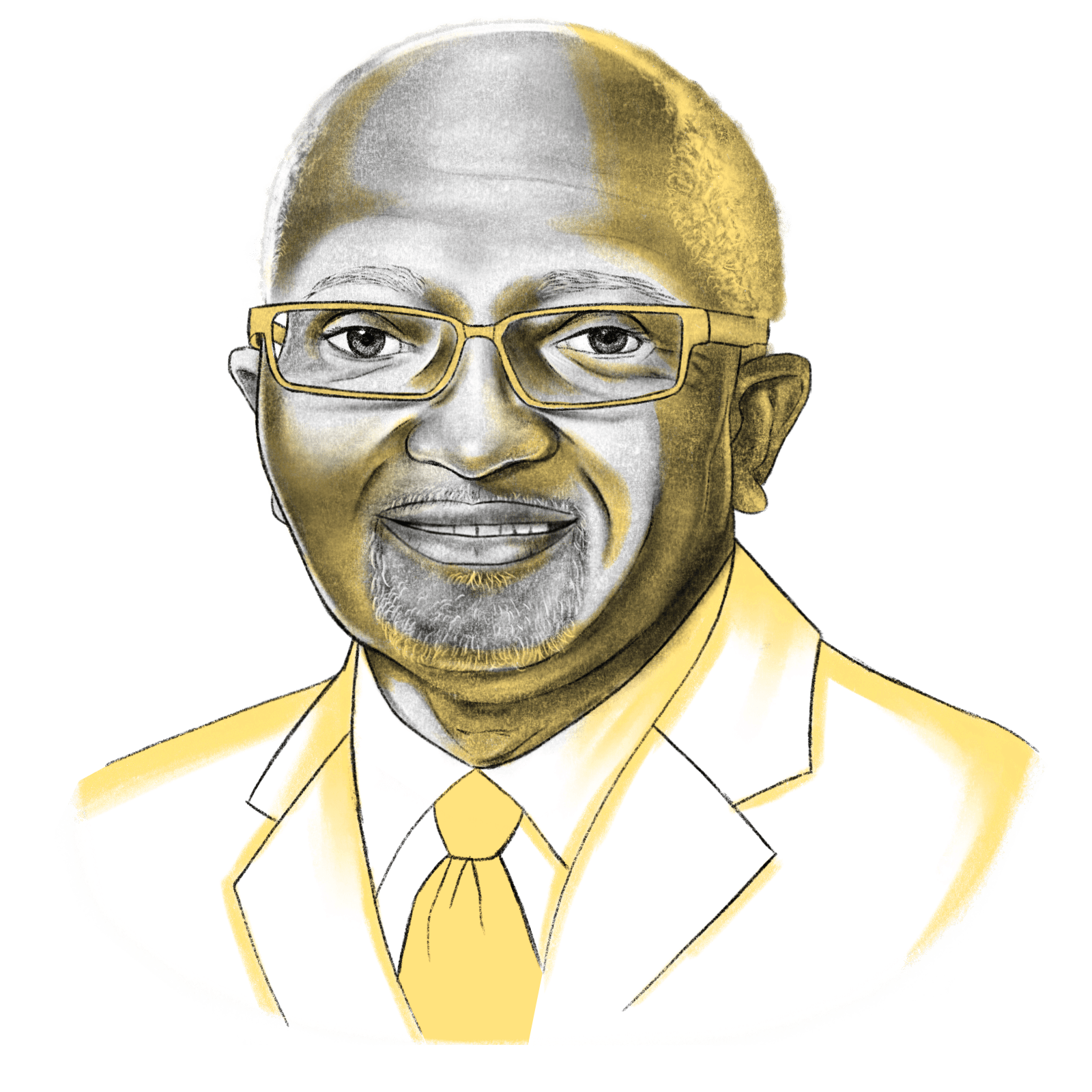

Dr. Robert Bullard was talking about environmental justice long before the term entered the political mainstream. His 1990 book Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality — an exploration of the siting of industrial facilities near Black, brown, and low-income communities, compromising residents’ health and fortunes — earned him the moniker “the father of environmental justice.” He’s a distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University in Houston and an award-winning author of 18 books on a broad range of issues from environmental racism and urban land use, to climate justice and community resilience.

If he was early to understanding the unequal environmental burdens faced by vulnerable communities — everything from living next to petrochemical plants to now residing near the front lines of climate-fueled extreme weather events — he believes 2020 is the year when the rest of the world caught up. “Let me just speak out from the heart,” he told Grist. “2020, I think, was a watershed year for justice.”

People connected the dots, Bullard said, as a result of images they were seeing on their televisions or phones and stories in magazines and websites. Communities of color suffered more deeply from the COVID-19 pandemic. Indigenous Americans are dying of the disease at nearly double the rate of white Americans; African Amercians face a rate that is 63 percent higher. The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbury, and others brought disparities in policing and criminal justice to the forefront. And in turn, Americans headed to the polls during the last presidential election in record numbers because they understood what was at stake: their lives.

Now with a new presidential administration in office, Bullard is watching to see if the issues that were uncovered last year will lead to lasting solutions to systemic problems in the future. Grist spoke to him about the prospects for both climate action and environmental justice over the next four years — and beyond. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q.We just marked the one-year anniversary of the World Health Organization declaring COVID-19 a pandemic. We’ve seen how it has devastated communities that have long borne the impact of pollution, particularly in Texas, which was just hit by this debilitating winter storm. Can you discuss the need for solutions put forth to address the climate crisis to also address long-standing environmental justice issues?

A.I think it’s important that people understand that we can come up with new policies that attempt to address our current situation as these natural and man-made disasters hit us. But if you talk about real solutions, we have to talk about systemic barriers and systemic policies and structural, institutional factors that are still creating disparities and vulnerabilities.

If we talk about the legacy pollution, communities that have borne the burden of pollution for decades (in some cases centuries), and communities that have been the victim of racial redlining, of neighborhoods and communities where the home loans were denied, insurance was denied, and where basic services were denied, you can see the footprint of that denial, of that racial discrimination, that may have occurred 100 years ago in the 1920s.

Solutions have to begin to address and unpack and unravel and attack those systemic factors that are still occurring right now, in terms of access to transportation that will limit people’s ability to get to a grocery store that may not be in a food desert, or getting access to a COVID test site that you may not be able to get to if you don’t have a car, or getting to a vaccination center that you may not be able to get to because there may be a limited number of pharmacies and health centers. And there are studies that show that poor people and people of color have to travel longer distances to get to all these things.

So the system planning will need to make sure to address the overlay of discrimination that will make communities of color more vulnerable in getting access to those things that will make us healthy, including a grocery store and including a site that’s been designated a vaccination center.

When the winter storm Uri hit us, it hit the state, it hit Houston, it hit all our major cities and hit rural areas. But the communities where the impacts were felt the greatest were communities where vulnerability is the circumstance in which most of these communities live 24-7.

Q.I’m wondering how you’re feeling right now, at this moment, about whether we can stave off the climate crisis and address environmental justice comprehensively?

A.I feel optimistic, hopeful, and positive right now. We are what, 50 days in? And looking at what the administration has been able to achieve, the way that they have framed the issues coming out the shoot, and the types of individuals that have been nominated to the various positions, as far as I’m concerned, it’s all good.

The environmental justice that we developed in 1991 is that people who are most impacted must speak for themselves and must be in those rooms when decisions are being made about their self-determination, their communities, and their livelihoods. They must be in the room. And I’m seeing a lot of that happening, filtering up. And that’s a good thing, as opposed to being top-down and being somehow told that this is how we’re going to do it. They’re into talking about engagement as partners, trying to make sure that there are metrics and there are measures — and there is accountability — that are being put in place in almost every major city that I work in and that I know people who work in. We know that there will be millions of dollars flowing back to our states and to our localities. And there has to be accountability at the local level so that when money hits the mayor’s office or development office, there will be accountability and that the money will need to flow to need.

Q.Can you say a little more about the idea of “flow to need”?

A.When the Biden-Harris administration talks about how they’re going to apply this equity lens, and when we talk about moving to this green economy and moving to green energy, and talk about the kinds of jobs and the kinds of resources that are generated, and how we’re going to use monies that come from this new economy — that they’re going to direct 40 percent to disadvantaged communities — these are the first communities that need to see the money and then the plans and then the programs. And the shovel-ready projects need to start rolling off the assembly line quickly. Because these are the communities that have been hurting for decades and have been left behind, ignored, have been invisible, and resources have bypassed them — even when billions of stimulus dollars roll into the state — which is the reason they get left behind. And we say no more. No more. They need to be in the front of the line. They need to be at the front of the queue as the lines form.

Q.Part of President Biden’s environmental justice plan includes rooting out the systemic racism in our laws, our policies, and institutions. What do you see as some potential solutions to address these deeply entrenched systemic issues?

A.If you look at the rollouts for the Biden-Harris administration in terms of how it is treating environmental justice, climate justice, economic justice, food security, food justice, you can see that there is a racial justice and equity lens that’s being applied. And I think a lot of that has to do with the kinds of participation and engagement that was broadened during this period that most of us were locked down. You can see it embedded in the way that the administration is looking at the issue of climate change, and the appointments that have been made that will be dealing with climate change, with environmental justice and the issues around equity and racial justice, the issues around health, and the issues around housing, the issues around energy, around transportation.

You can see with, for example, a department that has a history and legacy of centuries dealing with native Indigenous people in a way that is totally disrespectful. I’m talking about the Department of Interior, and I’m not afraid to call names. When you look at that nomination of Deb Haaland to be secretary of that department, that’s historic. It’s more than just an appointment, it’s sending a signal.

And when we see these kinds of signals being sent, and planning and programs being pushed forward, you can see that justice, as I said before, is at the core. They’re not running away from justice.