This story is adapted from the forthcoming book WARMTH, which will be published by Penguin Books in August.

There is no marked trail leading north from the town of Broome, Australia. There is only the beach, deep red and wide as a highway. On our first day of hiking, it seems to divulge a path of its own, our footfalls pressing moisture from the sand, forming little parched perimeters, like paving stones that appear as we walk. Sometimes the dynamics of this saturation are so complex and inscrutable that our strides unsettle sand that is several meters away, so that with each step we see little bursts of light up ahead of us, wherever the water is wicking through the grains.

To the extent that it’s known at all, this remote region of northwestern Australia is known for its beautiful sunsets, though it’s the moments just afterward that afford the true spectacle. After the sun disappears but before its light has fully left the sky — when the palette above the horizon mimics exactly the palette below and the radiance along its seam fades outward into the blackness of night and of dirt — it is possible to experience that old hackneyed sensation also induced by the surfaces of ponds and by particularly vivid dreams. Specifically, that you do not live in the world, but a version of it, and that behind its mirror there is another world, of equal weight, endowed also with the power of looking.

When the sky’s grown dark we stop hiking and set up camp behind the dunes. Of the several dozen people in our party, most are members of the Goolarabooloo clan, the Aboriginal family who for generations has served as custodian over this particular stretch of coastline. Daniel Roe, who in his mid-40s is one of the clan elders, builds a fire and invites everyone to sit down. In a low voice he tells us stories of another world, the Dreaming, which enfolds our own like a shroud. In this other world, everything is both itself and something else. Twin spits of rock are the fangs of giant snakes, and dry streambeds are the furrows left by the serpents’ windings. Three paperbark trees — out of place, set apart from any grove — are the digging sticks left over by three sisters, who have themselves become three pillars of rock further down the coast.

This correspondence between our world and the Dreaming extends all the way up to the sky, where Daniel points out a dark patch between Scorpio and the Southern Cross, a kind of anti-constellation. It is, he shows us, shaped unmistakably like an emu. In the cosmology of the Dreaming, the emu spirit helped create the world, traversing its details and singing them into being. When at last he grew satisfied, he stopped roaming and launched himself into the sky. The story goes that he remains there today, watching over his work, heralding the passage of the seasons. All of which is to say that absolutely nothing here is without agency. Even emptiness itself, the void between stars, can harbor enormous consequence, the hidden germ of your entire life.

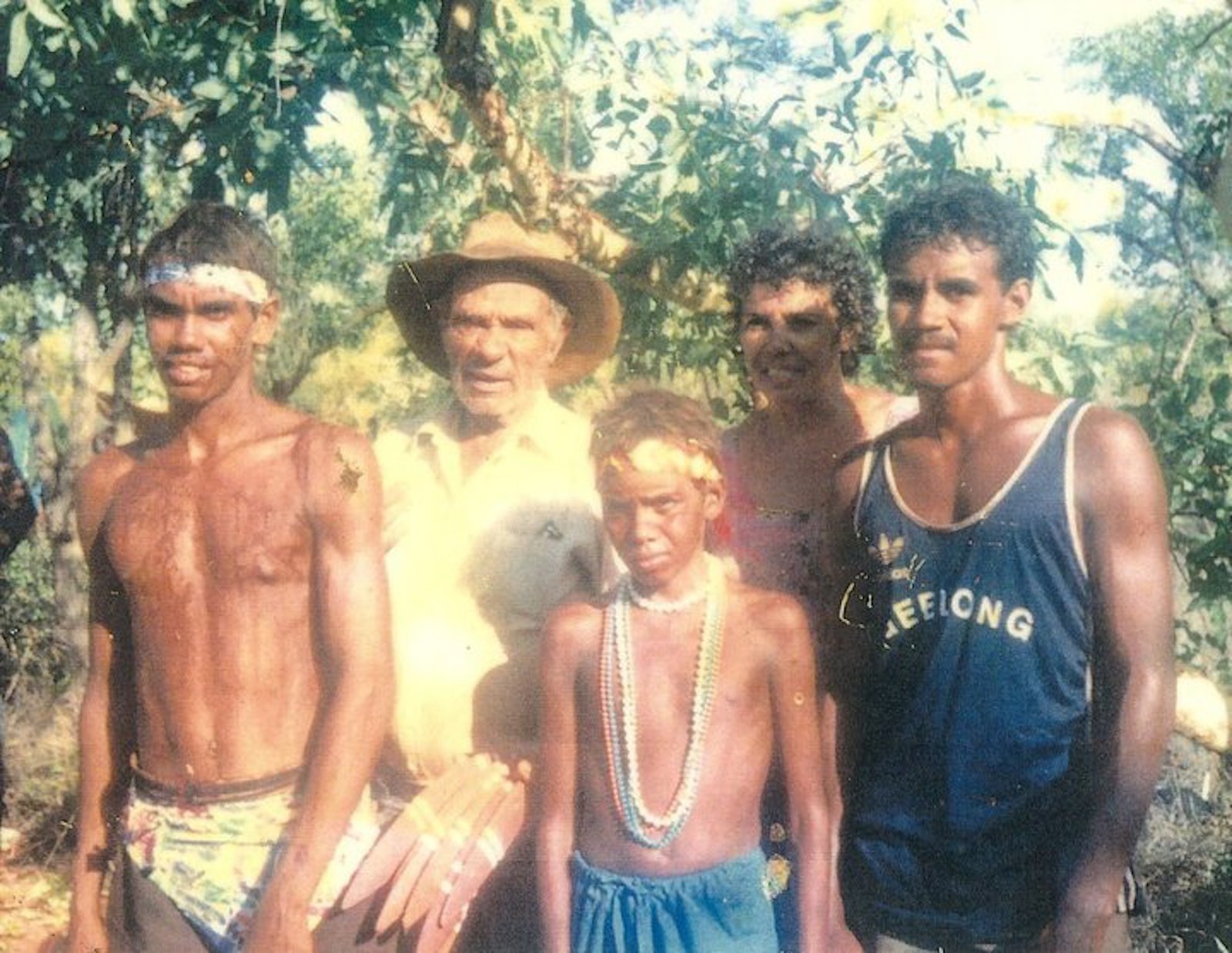

Every year the Goolarabooloo family walks this country twice, attending to it, keeping its company. They camp in the same spots, visit the same springs, scour for honey in the same paperbark trees. They invite a small number of non-Indigenous people to join each walk, a practice they began in the 1980s as part diplomacy, part charity — a means to “wake up non-Aboriginal people to a relationship with the land.”

The journey is about 56 miles, but the Goolarabooloo never rush it, stretching the trek out into a stroll over eight or nine days. Were John Muir or Henry David Thoreau to have made the same journey, I imagine they would have seen a wilderness here, a beautiful and mostly empty place in which to hoard their solitude. And indeed it is beautiful, this particular arc of coast. There are white dunes abutting cliffs the color of blood. There are dolphins that leap up in glimpses, and sharks that skim by on the prowl. Behind the dunes there are vast, muffled tracts of acacia and gum, vine-draped groves that spread inland for miles, their silence broken only by the far-off throb of the waves.

Few people live here, but the landscape is not empty. Wherever you turn there’s the thread of a story, the sight of a spirit. The country is not wilderness at all but crowded, dense with characters and plots, dangers and havens, rules and obligations laid down over millennia. Connecting all of this is a walking route, a physical course through the landscape, variously referred to as a heritage trail, or a Dreaming track, or a songline. To follow the trail is to plot the land, to replenish it with narrative. And so every year all the aunties and cousins and grandbabies of the Goolarabooloo clan come out here to give time and pay attention — and prevent the two worlds from collapsing into one.

In the late 2000s, the fossil fuel conglomerate Woodside Energy petitioned to build a liquid natural gas processing plant 30 miles north of Broome, on a peninsula known in English as James Price Point, and to the Goolarabooloo as Walmadany. The proposed plant would stretch across 2 square miles of land, a region of red sand and gray brush directly in the middle of the songline. The state premier at the time — a jowly white man named Colin Barnett — referred to the site as an “unremarkable stretch of country” and went on television to stump for its development. When the clan saw this, they knew a collapse was at hand. Already their land was being spliced up into a grid of numbered parcels. If construction moved forward, pipelines would supplant all the plotlines.

And so they fought it, erecting a protest camp out at Walmadany, only a few hundred yards from where Woodside had built its beachhead, a fenced-in compound of low huts and machinery, patrolled around the clock by private security personnel. News spread quickly around Broome. Local businesses started sending food and supplies up to the camp. Tradespeople loaned their equipment. A crew of citizen scientists set up a survey platform to monitor the humpback whale migrations just offshore, gathering data that plainly contradicted Woodside’s rosy environmental impact statements. The standoff went on for months, then years. For long stretches the protest camp had over a hundred residents, a rotating cast of journalists, academics, drifters, locals, and activists from faraway Sydney and Melbourne. Many of the non-Aboriginal people who came out were those who in years past had taken part in a walk of the songline. For the Goolarabooloo elders presiding over the camp, all of this was as planned. Inviting “whitefellas” to walk the songline had never been about tourism. All those years, they’d been building a constituency.

Eventually the protest caught the attention of some larger organizations: the Australian Green Party, the Tasmania-based nonprofit Wilderness Society, and the Sea Shepherd, a marine conservation group. Rallies were held across Australia: 5,000 people gathered in Melbourne, 20,000 in Perth. As the project delays lengthened, the Woodside security personnel grew more aggressive. They’d show up to camp in the middle of the night, shining flashlights into tents and pointing video cameras in peoples’ faces, their own name badges blacked out with tape. The protesters started escalating their tactics, too, locking themselves to bulldozers and drill rigs. Finally, in 2013, Woodside threw in the towel. Company executives laid the blame on falling gas prices, but many of their joint venture partners — fossil fuel goliaths like Chevron and Shell — had already pulled out. They’d expected free reign in this obscure and “unremarkable” country. They’d expected it to be empty.

The victory came three years before the protests against the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock. A tiny Indigenous clan — no more than a few extended families — had beaten back some of the largest fossil fuel companies in the world. And yet the news barely traveled outside of Australia. In the years afterward, the Goolarabooloo sank back from their brief prominence, quietly continuing their walks up the coast they’d improbably saved.

On our second day walking the trail, I approached Daniel, mid-stride, and began asking questions about the Dreaming. It was July 2019 — winter in Australia — but the temperatures in Broome still sat comfortably in the low 80s. Daniel was wearing a baseball cap and wrap-around sunglasses, and his flip-flops slapped as he walked. I asked him about the meanings of certain rocks, the use of various shrubs. He let me prattle on for a few minutes before gently rebuffing me. He’s noticed, he said, that whitefellas like to have a chat as they walk. They like to pass the time. But sometimes silence is the best thing: It lets you pay closer attention to the country you’re walking, lets you notice things you wouldn’t otherwise. Chastened, I tried my best to keep quiet and turn outward to the business of noticing. I stared dutifully at many things, but could only attend to some of them. I noticed, for instance, a wattle tree whose yellow flowers looked as thin and bristled as pipe cleaners.

I noticed another with white flowers, fatter and more silken, like bolts of yarn. I noticed that the shadows which sometimes crossed our own belonged to two distinct kinds of raptor, and that if you really scanned the sand you could spot the prints of dozens of animals, among them the hermit crab, whose tracks looked like the tread of a tiny bike tire. I did not notice the small holes in the paperbarks that indicated the presence of honeybees. I did not notice, until one of the aunties pointed it out to me, that the tide sometimes stranded minnows in the little lagoons, and that these could be gathered up pretty easily for bait. My attention was ill-trained, but those few things I did manage to observe I found myself needing to share with someone, as if to set their beauty down in record.

Look at those cliffs, I said, look at that bird. Look at how the sun catches the water like a net. Eventually the beautiful things became too numerous to name, and I shut up about them, letting them sit there in my head, gradually shedding their metaphors.

There were many children on the trail, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the Goolarabooloo clan, and most of them wore no shoes. They chased after each other over hot sand and sharp rocks, and after they’d tired would walk for hours in the shell of their thoughts. But though I tried to pay attention, I never once saw them examining the ground in front of them, deliberating over where to step. Their soles were thick, and they seemed to look only ahead, or around, or at nothing. My own feet got cut as I walked, and the cuts packed with sand, but it’s an easy thing to walk down the beach and let the water wash them clean.

The next day we came to a brackish creek with wide banks and a slow current. The creek was too deep to cross by wading — and is anyway home to large crocodiles — so we waited for a metal dinghy to ferry us the short distance across. While we waited, Daniel told us about the tides, which in recent years have grown significantly higher, spilling over the sides of the creek and wearing away at its banks. The flooding got so bad one year that the rising water washed out a sandbar containing an important ancestral burial site, dissolving it in a matter of weeks. Later, some white tourists happened upon the bones, clearly human, scattered here and there along the beach. Daniel reckons that they could’ve been a few thousand years old, though an analysis was never done and he has no way to confirm this.

As he spoke he reminded us that the floods were not a localized aberration. The creeping tides were a product of worsening climate change, a far greater threat than Woodside had ever posed. This shouldn’t have been surprising but was, somehow. Without fully realizing it, I’d become invested in the idea of the songline being “saved,” as if the expulsion of the gas company had created a permanent haven, beyond the reach of our planetary crisis. To Daniel this was plainly untrue — a fantasy of purity sustainable only if you weren’t paying attention.

The Aboriginal economist Tracker Tilmouth used to deride this fantasy of purity, the way it could extend from a land to its people. There were some environmentalists, he’d say, who preferred to see Indigenous communities as forever static and pristine. Indeed, among the white people on the trail, I sometimes noticed us talking about the Goolarabooloo as if they were saints or saviors, emissaries from the past come to deliver some immutable piece of wisdom. People spoke in hushed tones about their humility, their alertness, their skill with a fishing spear. None of these things were untrue, necessarily, but the romanticization felt like its own kind of stereotyping, and anyway didn’t admit the whole story.

Out on the trail, the Goolarabooloo did not conform to any fantasy of themselves: They ate cup noodles and smoked menthols and drove giant pick-up trucks across the beach. Many members of the family didn’t physically walk the track at all, but would instead pile into the beds of the trucks and get to the next camp early, so they could spend the whole day fishing. On one occasion, I hitched a ride down the beach with an uncle who was wearing a Kobe Bryant jersey and a mullet, and whose jeep had no windows or license plates. When we somehow popped a flat, he just inflated the still-perforated tire and sped us back to camp, the entire chassis listing more and more to the left.

All of which is to say that between the two worlds, it is possible for a trip down the trail to be at once a spiritual rite and a family vacation, and that the messiness and petty comforts of the latter do not negate the sincerity of the former, the genuine will to spend time with the country.

Archaeologists and anthropologists generally consider Aboriginal culture to be the longest-running continuous culture on the planet. According to most estimates it is 60,000 years old, give or take. To get a sense of just how old this is, it may be helpful to consider that only 15,000 years ago, the land that is now New York City was buried in darkness under a mile of ice. So when Daniel and his relatives invoke the holy sentience of their country to ward off the corporations who would demolish it, they are drawing on a cosmology whose sheer longevity makes the birth of Christ look recent.

Given all this talk of prehistory, it is often wrongly assumed that the Dreaming is located somewhere in the deep past, a period so distant it can now be populated safely with myth. But if you ask the Goolarabooloo clan, they will tell you that the Dreaming is ongoing, that it never ended nor could it, really, because what would it mean for the land to suddenly lose its train of thought? When exactly was the moment when the water and the rock and the snakes and the storms relinquished all agency, when they stopped telling their own stories? The whole premise is absurd — that we could consider ourselves so detached from the world on whose umbilical grace we still palpably rely, that it would actually become possible for us to drill into it without expecting a reply.

The anthropologist William Stanner has argued that the Dreaming occurs in the “everywhen,” a time so fluid and capacious that sequence fades toward irrelevance, a minor detail impeding comprehension. Which is to say that there are times much bigger than the “present” conceived by Western philosophy, with its constant arrivals and departures, its flitting brevity. Had Woodside succeeded in building its plant over the songline, it would not have constituted an erasure, like paving over a monument. It would have been more like an interruption — like killing a storyteller mid-tale.

There is a temptation to locate a panacea in these ideas, an escape hatch from our troubled times. But this would be a mistake. At a symposium I attended the month after I returned from the trail, the Aboriginal writer Alexis Wright said that, in matters pertaining to the climate crisis, “it’s become a bit of a fashion to talk about Indigneous knowledge, to try and package it.” Of course, she went on, what is often referred to as the “Indigenous worldview” does have much to offer us on this front: concepts of interdependence and non-linear time and non-human sanctity, a “long vision” that can learn from generations past and account for generations to come. In a time of worsening floods and droughts, all of these concepts, once dismissed as idealistic, are revealing themselves to be the most clear-eyed kind of pragmatism.

However, Wright warned, no Indigenous culture was ever static; it was always adapting to its time. It was therefore ludicrous to hope that Aboriginal culture would have some silver-bullet answer to ecological catastrophe. In fact, she told us, “I have no doubt that our struggle to survive will become far more enormous than the catastrophic realities of our current time.” So she did not want to give the impression of offering easy reassurances packaged as fail-safe ancient wisdom. She was very clear on this point: “What I’m trying to deliver to you is something I’m grappling with myself.”

The irony here is almost cosmic: After centuries of colonization and exploitation, the European world is beginning to look for salvation in the minds of the very people it dispossessed. It’s true that Aboriginal civilization has survived 60,000 years without precipitating a global environmental crisis, while so-called ‘Western civilization’ has managed to bring one about in just a few thousand — in part by robbing Indigenous people of their lands and siphoning off the fuels underneath them. But herein lies the danger: If we in the West choose to mine Indigenous culture for solutions the same way we mined Indigenous land for carbon — engaging not with people but with whatever idea of them best suits the program of our relentless prosperity — then any succor we find will be temporary, another trap we’ll have sprung on ourselves. We cannot extract our answers any more than we can outsource our questions. If we’ve already decided what we’re looking for, we won’t find anything new.

I thought about this often as I was walking the trail — how when I was looking for something in particular, I never seemed to notice it. True noticing involves an element of surprise, a vulnerability to the unexpected. And so I am not going to offer an easy nostrum dug up from some Indigenous idyll. All I can offer are a few wrinkles in the picture, things I noticed when I wasn’t looking for them. For instance: Aboriginal people are often spoken about as having an emotional connection to their country, and indeed Daniel himself speaks in exactly these terms. But the assumption that often goes with this — at least the one I myself once subscribed to – is that the emotion being described is always something akin to love or respect or harmony. The Goolarabooloo people I met do love their country; they love it fiercely, with a fealty that leaves me in awe. But they also sometimes fear it, or compete with it, or grow impatient with it. In camp at night, aunties would warn me about sleeping under certain trees. They’re bad luck, those trees, they’d tell me; they’ll bring you nothing but trouble.

Sometimes we’d pass by whole sections of forest that the men weren’t allowed to enter, or the women weren’t allowed to enter, or everyone generally was advised against. The spirits there were too dangerous, we were told, and we listened. And it shouldn’t come as any sort of revelation to know that members of the clan sometimes expressed frustration when the fish weren’t biting, annoyance when the sun made them sweat, and mild boredom when the walks took too long. This was the relationship to the country I noticed: not a simple romance but the full spectrum of feeling — the mundanity, the variety, the sheer detail — that comes with being part of a family.

In one of the TV interviews he did during the Woodside controversy, Premier Barnett was asked about the Goolarabooloo’s opposition to the gas plant. I understand, he said in a tone that indicated he did not, that they have an emotional connection to that area, but we can’t let that get in the way of economic progress.

We can table for a moment the long-term economic madness of investing in an industry slated to crater gross domestic product in the coming century. What was most revealing about the premier’s condescension was the fundamental difference it laid bare: not between love and disdain for the country, but between any emotion and none at all. Between a people whose bond to the land was familial, and an official who refused to imagine what that meant.

Though the Goolarabooloo succeeded in defending this bond, their victory over Woodside came at great cost. There are other Aboriginal people in town who still won’t talk to them, bitter at the loss of Woodside’s long-promised plant jobs. Daniel’s uncle Joseph — who effectively led the anti-gas campaign and spent years dashing from rally to rally — died at 47, struck down by a stress-induced heart attack 10 months before Woodside canceled the project. In Aboriginal culture, it is taboo to speak the names of the recently deceased, so I never heard his name said out loud by any member of the family. Even when they recounted the long history of the campaign, they mentioned Joseph only by implication, skirting around him like a hole in the narrative.

Despite this, there are no regrets. The clan has witnessed what’s happened on the Burrup Peninsula, just down the coast, where the gas industry got a foothold and never let go. I’ve been there myself, and the contrast is terrifying. The peninsula has become a piece of infrastructure, like the hydraulic arm of some immense machine, its flatlands obscured by mazes of pipe and industrial wharves and storage domes the size of the surrounding hills. Most areas of the peninsula are closed to the public now, requisitioned behind razor wire and guards’ huts.

In the middle there is a tiny national park squeezed between the fences. On the sides of the red boulders lining the park’s jagged hills, there are rock carvings which date back 30,000 years. The carvings are faint, but if you look closely you can make out emu tracks and boomerangs, ghostly people with long arms and domed heads. Many of the rocks are engraved with symbols whose meanings have been lost, though when I visited I would from time to time spot a carving whose candor and familiarity took my breath away. Pecked into the underside of one boulder, for instance, I found the perfect, sinuous figure of a dolphin, not an ideogram but a portrait, as if the artist had caught it mid-leap. It is said also that the carvings on the peninsula include the oldest known representations of the human face, though it is unclear how many of these have been bulldozed by the gas plants, which is only part of what I mean when I say the landscape has been defaced.

On our sixth day walking the songline, we reach our final camp. On the seventh day we rest. People lay out mats in the shade, or drift off to wander the bush. I accompany some of the younger cousins down to a reef near the shore to spend the day fishing. It’s low tide when we get there, and the reef has revealed its face, a platform of greenish rock extending a hundred yards out to sea. One of the cousins, a man about my age, wants to show me how to cast a handline, and we spend half an hour practicing how to hold the cheap plastic spool, how to flick your wrist so the line doesn’t catch. I’m useless at first but manage eventually to land my hook a decent ways out, and the cousin is satisfied enough to head off on his own. I watch him stalk the edge of the rock staring down into the ocean, an old T-shirt wrapped around his head. In one hand he holds a lit cigarette and in the other a wooden spear, and when he leans back to throw the spear he squints his eyes and clamps the cigarette hard between his lips.

The rest of the cousins are spread out along the reef, fingers testing their lines, which angle and glint into the surf. In two hours they’ve pulled up a dozen fish — mackerels and butterfish and Spanish flags — unhooking them deftly and chucking them into tide pools, where they continue to swim in tight circles. I only ever catch rocks, but I don’t mind; it is good just to be out there, standing still in the spray from the waves. As the afternoon passes, it leaves tracks across my skin: the cut of the line, the heat of the sun, the salt that dries white on my arms. There are delicious little oysters studded around the reef, and sometimes I pause to go crack one open, though the rock is so sharp that even in sandals I am forced to walk very slowly, feeling the shape of every step.

When we return to camp that night, some of the older men have caught a sea turtle, and its shell sits like a giant shield over the embers of the fire. As its meat is passed around we are regaled with the story of its capture. Apparently the uncle who spotted it isn’t allowed to spear turtles right now because his wife is pregnant, so instead he had to call on his brother, who threw so hard he pierced the shell in one go. There are all sorts of complicated taboos like this, about who can hunt what and when. Many people here have totem animals, creatures they consider to be close relatives and so abstain from killing. It has been suggested that this totemism functions as a mode of sustainable management, limiting the number of animals hunted by any one clan in any one season, though the Goolarabooloo talk less in terms of “management” and more in terms of relationships — relationships of rivalry and reciprocity, of giving and taking, relationships too knit to untangle.

Whatever this country is, it is certainly not a wilderness, to be preserved and left alone. It’s a place to be engaged with, to be felt, to be speared and noticed and sung into being. Sometimes when I think about the enormous violence of climate change, I feel so guilty in my humanity that I’m tempted to recuse myself entirely, to bolster that arbitrary line between ‘people’ and ‘nature’ and then retreat behind its wall. But this is a fantasy of extinctionists and extractivists — that we could ever fully sever our connections, that it would even be possible to choose one world and forego the other. As Daniel likes to say: “Country needs people.” You can’t withdraw when you have a role to play.

Still, if Woodside had won, it would have done its best to effect an untangling. This would have proceeded stepwise, through a series of abstractions. First the country would have been abstracted into soil, then the soil would have been abstracted into acres, then the acres would’ve been abstracted into a site, then the site — having been abstracted of all vegetation — would at last have been abstracted into a plant. Then the plant would have set about its business of abstracting fossils into fuel, which would in turn have been abstracted into markets, which would have done their job of abstracting the fuel into currency, which might afterward have been abstracted into derivatives or futures, so that by the end of the process the final traces of the original country would be contained only in tiny symbols on the screens of financiers, tiny molecules accruing invisibly in the atmosphere.

One might be tempted to claim that the Dreaming too is an abstraction. But if this is true then the same can be said of Barnett’s preferred stories, those superstitious fables of invisible hands and endless growth and anthropic dominion. And where the stories of the Dreaming grow out of the country, the stories of the Barnetts just pave over it. Their stories are narrow and inharmonious, accommodating only a single world, whose persistence requires all others be silenced.

And so we walk, against this silence, across the beach. We walk to remember the country, not what it might be but what it is, what it feels like. We walk because we want to notice, or maybe be noticed: to place our ears, eyes, nose, mouth, and skin to the ground, so it can speak to them, finally, as it will. Because it is harder to abstract stones that have cut your feet, harder to abstract fish that you’ve reeled in and eaten. None of this is a solution, of course: We cannot simply walk our way out of an ecological crisis, nor can we expect the Goolarabooloo to carry us. But as our collective future deepens, maybe walking will prove itself a useful form of thought. Just to tread lightly, without intent, to step through the symbols and into the sand.

On our last day of walking, we reach the country where the plant would have gone. The cliffs are tall here, and deep red, and there is a joy in standing under them, looking up at their faces and knowing they’ve been salvaged. Barnett was wrong to call this country unremarkable: All around it are the tracks of dinosaurs, hundreds of millions of years old, the fossils of other walks, preserved in stone and set down in the everywhen. The largest of the footprints is nearly 6 feet across, the print of a sauropod thought to be the biggest animal ever to walk on land. It looks from afar like a giant tide pool, and when we arrive Daniel is standing in the middle of it, smiling. The clan has known about these tracks for ages, and lately they’ve been collaborating with paleontologists to document their variety and extent. Had the conglomerate built here, they would likely all have been lost, and they may still disappear beneath the rising tide. But for now they are right in front of us, and so we walk into them, plant our feet inside theirs.

Nearby there are smaller tracks, three-toed, distinct. To the paleontologists, they are the tracks of a theropod; to the conglomerate, the traces of fuel. Both these things are true, but also: Witness the tracks of the emu, where his spirit stepped off and ascended.

From WARMTH by Daniel Sherrell, to be published on August 3, 2021, by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Daniel Sherrell.