This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

On an early August morning in 2021, a family — two parents in their 30s and 40s, their 1-year-old, and a big dog — set out on a hike in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. The temperature was a comfortable 70 degrees Fahrenheit when they started out, but the day became dangerously hot as the four began the climb back up to where their truck was parked. At ground level, the temperature was likely hotter than 110 degrees F. They never made it back. All four of them — the dog, the parents, the baby — died on the trail.

County sheriffs struggled to determine what caused a healthy family to drop dead with no evidence of foul play or struggle. Was it toxic algae from the river that flowed along the bottom of the gulch they hiked beside? Did they accidentally breathe in carbon monoxide from an open mine shaft near the trail? But the answer was right in front of them the whole time. Two months after the bodies were found, authorities announced the official cause of death: hyperthermia and dehydration. The family had overheated.

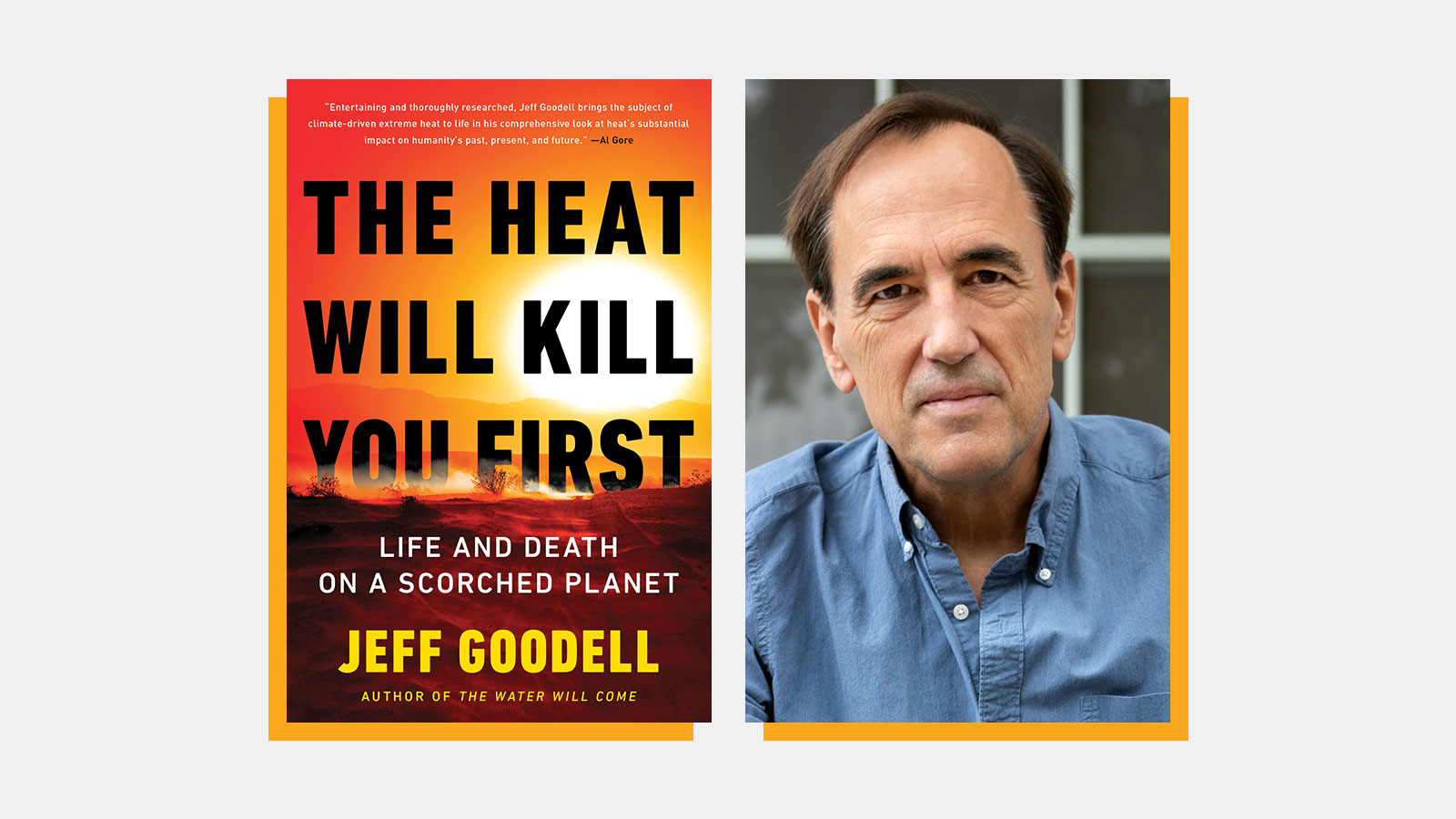

That story is one of many examples of heat’s deadly toll in The Heat Will Kill You First, author and climate change journalist Jeff Goodell’s new opus about extreme heat. “If there’s one thing in this book that will save your life,” Goodell writes, “it is this: … if your body gets too hot too fast — it doesn’t matter if that heat comes from the outside on a hot day or the inside from a raging fever — you are in big trouble.”

Heat is an invisible, stealthy force, Goodell explains. Because we’re all familiar with it, we think we know how to handle it, how to game it. But heat can’t be negotiated with past a certain threshold — if your body gets hot enough, you die. It’s as simple as that.

The Heat Will Kill You First reveals how heat has fundamentally shaped the arc of human evolution, perhaps even inspiring our ancestors to stand upright, off the hot ground, millions of years ago. The book’s take-home message, however, is about the future. Humans have changed the natural course of the planet. Climate change is forcing us out of the temperature range we’re used to and into uncharted territory. What comes next?

“My goal in this book is to help people understand what risks we face as our world gets hotter and hotter,” Goodell told Grist. The Heat Will Kill You First is available this week in bookstores and libraries.

This Q&A has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Q.In your book, you sketch out a full spectrum of heat-related catastrophes across the globe — a deadly heatwave in Paris, the deaths of migrants in the Sonoran Desert, hurricanes in Houston. What overarching story are you trying to tell by bringing those various threads together?

A.I think the overarching idea is that our understanding of the threats and risks of extreme heat is very nil, and that the risks and threats have been greatly underestimated. I really wanted to write about heat as this kind of invisible force in our world. We talk about things being hot in a kind of complimentary way where we meet somebody and they’re hot or we see a new movie and it’s hot, but we don’t really think about what heat is. And my goal in this book is to articulate that.

Q.There are so many climate impacts that are so visible. Heat, as you say, is invisible but it’s extremely visceral once it hits.

A.When anyone talks about climate change, they talk about the litany of things that climate change is going to do: the longer droughts and higher sea levels and increased precipitation and stronger hurricanes. But heat is the primary driver of all this stuff. The reason that the wildfires are burning in Alberta, the reason that there are orange skies in New York is all because of more and more heat. Heat is like the engine of planetary chaos in our world. But it’s very difficult to communicate about because it is not like a hurricane where you have dramatic images of storm surge coming in and trees blowing around and roofs flying off houses. Heat is literally an invisible force that is profoundly shaping our world.

But heat is also really hard to talk about and think about partly because it’s so familiar. I mean, everybody knows temperature, right? Everybody knows what a hot day is, a cold day is. Babies know this, right? I started writing this book when I had to take a walk in Phoenix 10 blocks or so downtown. And I thought I was going to die, it was so hot. And I realized that not only did I not understand the risks of heat and what it does to our bodies, but I didn’t even understand what heat is. And this is after I’ve been writing about climate change for 15 years.

Q.There’s a perception in the wealthy West that climate change will affect us more slowly than other parts of the world. And while that’s true in many ways, you make the case in your book that heat is a universal, democratic force. Can you speak to your conception of heat and how it’s moving through society?

A.Everything that lives, whether it’s me or you or your mom or my mom or your ancestors or the pine trees in the backyard or the ants crawling across the floor or the lions in Africa, they all have thermal limits that they live in. Our bodies are very sensitive to heat. We work really hard to keep our bodies to 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit or thereabouts. And if it goes just a little bit off, I mean, everybody knows if you get a temperature of 101, 102, you’re in trouble. Something’s really wrong. Get to 105 and you better be in an emergency room. So it’s a very narrow range, and that affects all living things. Everything about our world has evolved in this sort of stable climate niche. Not too hot, not too cold, this kind of Goldilocks climate. And as we continue burning fossil fuels and dumping CO2 into the atmosphere, we’re moving out of that Goldilocks climate.

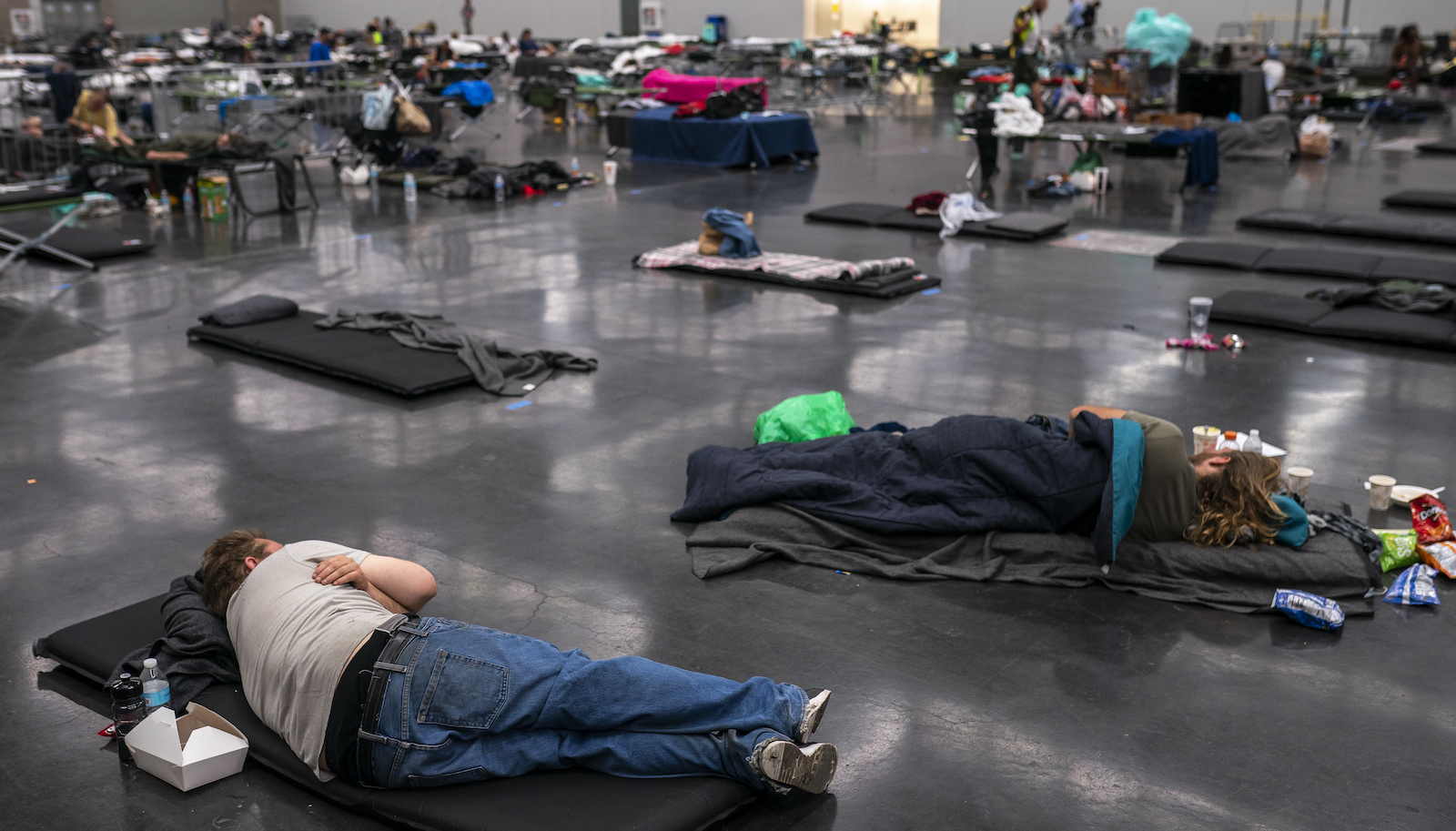

So heat is profoundly democratic in the sense that it affects everyone and everything that lives. People are saying, “Oh, well, yeah, that’s true, maybe. But, you know, we have air conditioning, we’re going to adapt, we’re smart and all that.” And that’s true. We are going to adapt. We do have air conditioning. But not everybody has air conditioning and not every thing has air conditioning. We’re not air conditioning the air. We’re not air conditioning the forest. The cornfields, the wheat fields that produce the food that we eat.

And there’s a profound gap in every city, everywhere, between people who have air conditioning and people who don’t. I wrote about that a lot in my book, this gap between the “cooled and the doomed.” So, yes, we can adapt. But even this notion that you and I are going to be OK, the rich Westerners, because we have air conditioning — well, yeah, fine, except when the power goes out. If you have an extreme heat wave like we’ve been having in Texas, and in the middle of that you lose power for a day or two, people will die. Lots of people, thousands of people. And so our comfort and sense of reliance on air conditioning is also in itself very dangerous.

Q.You’re publishing a book about heat, one that I assume was in the works for a number of years, at an extremely auspicious time. The globe is breaking heat records. The first days of July were the hottest ever recorded in human history. Did you think this might happen?

A.It would be funny if I could say, “Yes, I knew that in July of 2023, when my book was published, that we would have this extreme heat wave.” But no, it’s really weird. It’s like I’m living in my own Stephen King novel. It’s very eerie and spooky. But, that said, when I started this book in 2019, heat was not exactly a secret anymore. We’ve been talking about global warming for 30 years, 40 years. But it became clear to me that we hadn’t given it full consideration. So it seemed like fertile ground for a book.

I had no idea that this summer was going to happen and unfold the way it has. But there was a certain inevitability four years ago, when I started the book, that heat was going to become more and more of an issue because, after all, we are heating up our planet very quickly. And so understanding heat and how to deal with it and what the risks and dangers are seemed to be a pretty important question.

Q.You’ve been a climate reporter for many years, which means you’ve been witness to the many, many iterations of the public’s understanding of climate change. How does this moment feel to you now? Do you feel like we’ve entered a new era?

A.There’s certainly been a cultural shift about it, right? When I first started writing about climate change, I would tell people that I ran into at dinner parties or whatever that I was writing about climate change and they would kind of look at me with this cute little smile as if I was writing about the sex life of porcupines or something. And now everybody’s talking about it. The impacts of it economically and impacts on public health — it’s much more mainstream in the sense of it being a subject of discussion.

But we are — and heat is a great example of this — we are not even at the beginning of the beginning of the beginning of understanding the implications of what we’re doing and understanding the consequences of what we’re doing. I don’t mean that just in the grandest way, but also just in the simplest way. We don’t really understand how fast this can happen and what the real tipping points are.

Two years ago, in 2021, we had an extreme heat wave in the Pacific Northwest that everybody heard about. It was 121 degrees in British Columbia. No climate model was thinking about that, it was like snow in the Sahara or something. And it just shows how complex the system is that we’re messing around with. The great scientist and oceanographer Wally Broecker said two decades ago that dumping fossil fuels into the atmosphere is like poking a dragon, you never know how the dragon’s going to react. And that that is still as true today as it was 20 years ago when he said that.