Trees tumbled, trucks flipped, and solar panels flew through the air in Guam as Typhoon Mawar pummeled the U.S. territory in the western Pacific on Wednesday morning. The slow-moving, Category 4 super typhoon unleashed hurricane-force winds, gusting over 150 miles per hour and leaving tens of thousands of people without power. Floods from a surging sea and relentless rain could pose an even greater risk to the island, although the extent of damage caused by the storm isn’t clear yet.

Guam is no stranger to typhoons. The last major one, Super Typhoon Pongsona, struck in 2002 and caused $700 million in damage. But Mawar is the strongest since then — and it likely was made more intense, and more dangerous, by climate change.

As the planet heats up, oceans do, too. Warming seas generate more fuel for cyclones, which feed on hot air and water vapor lifting off the ocean’s surface. Rising sea levels worsen storm surges — up to 10 feet in Mawar’s case — heightening the threat of floods. And higher air temperatures trap more moisture in the atmosphere, which causes typhoons like Mawar to dump more rain. The storm has been pelting Guam with up to two inches of rain an hour.

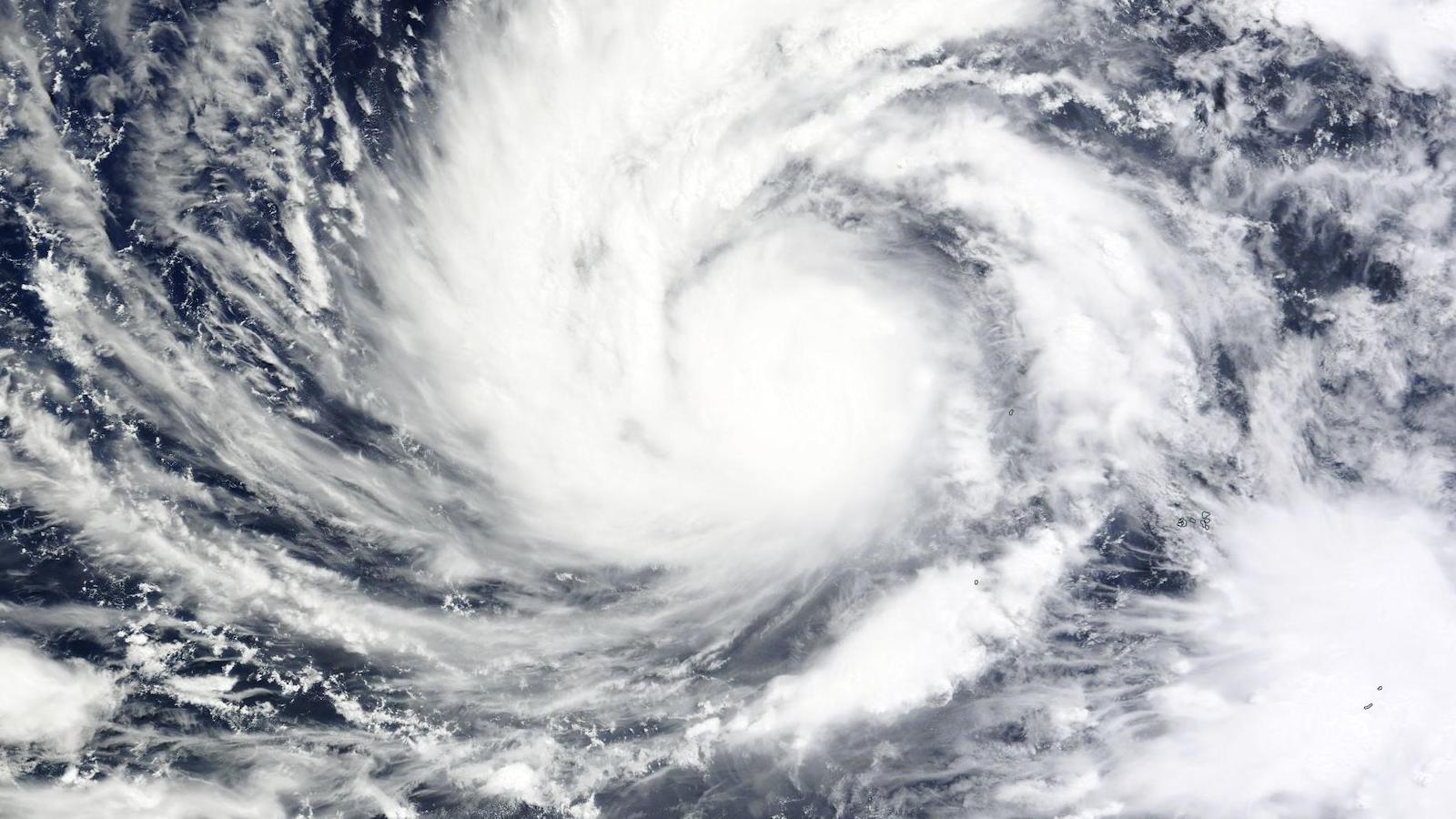

The eye of Mawar passed just north of Guam, as its southern wall — the windiest part of the storm — lacerated the island of some 170,000 people. As of Thursday morning, no storm-related deaths had been reported.

“I will be making an assessment of the devastation of our island as soon as it’s safe to go outside,” Guam Governor Lou Leon Guerror said in a video posted to Facebook. She was inside, but as she spoke, wind could be heard thrashing the building. “We will get through this storm as we have in many, many other storms.”

President Joe Biden preemptively declared a federal disaster emergency on Tuesday. Stronger building codes have minimized damage and deaths from major storms on the island in recent years, the New York Times reported. Usually, “we just barbecue, chill, adapt” when storms hit, Wayne Chargualaf, who works at the local government’s housing authority, told the Times. Still, the National Weather Service urged residents to hunker down, describing “destructive winds, life-threatening storm surge, and torrential rain, which may result in landslides and flash flooding.”

Mawar whipped from a Category 1 into a Category 4 storm in just a day, and weather experts say typhoons and hurricanes are charging up and transforming into mega-storms more quickly as the planet warms. Some of the recent major hurricanes in the U.S. intensified right before landfall: Hurricane Ian, which slammed into Florida last year; Ida, which ripped across Louisiana in 2021; and Harvey, which hit Houston with historic floods in 2017. Such rapid escalation can catch officials off guard and make preparing more difficult.

Scientists are also investigating whether climate change is causing tropical cyclones to slow down. Mawar was moving at only eight miles an hour on Wednesday evening, while other typhoons in the region have sped up to 15 miles per hour, a meteorologist told the Associated Press. Some research suggests that human-caused warming has kept storms sitting longer over land, causing more flooding, as was the case when Harvey lingered above Texas and Louisiana for several days.

The global El Niño weather pattern, expected to arrive later this year, could make severe storms near Guam more likely. The westerly winds that define the pattern are forecasted to warm the ocean’s surface, shifting the area where cyclones develop, and putting the islands of Micronesia, including Guam, at greater risk, according to the National Weather Service. The World Meteorological Organization recently warned that the pairing of El Niño with climate change could make the next five years the hottest on record.

The National Weather Service plans on releasing an official outlook for Guam’s tropical cyclone season on June 1, which just happens to be the start of hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean. Forecasters say this season could be similar to 2017, the year of Harvey and Maria, which wreaked havoc across the Caribbean.