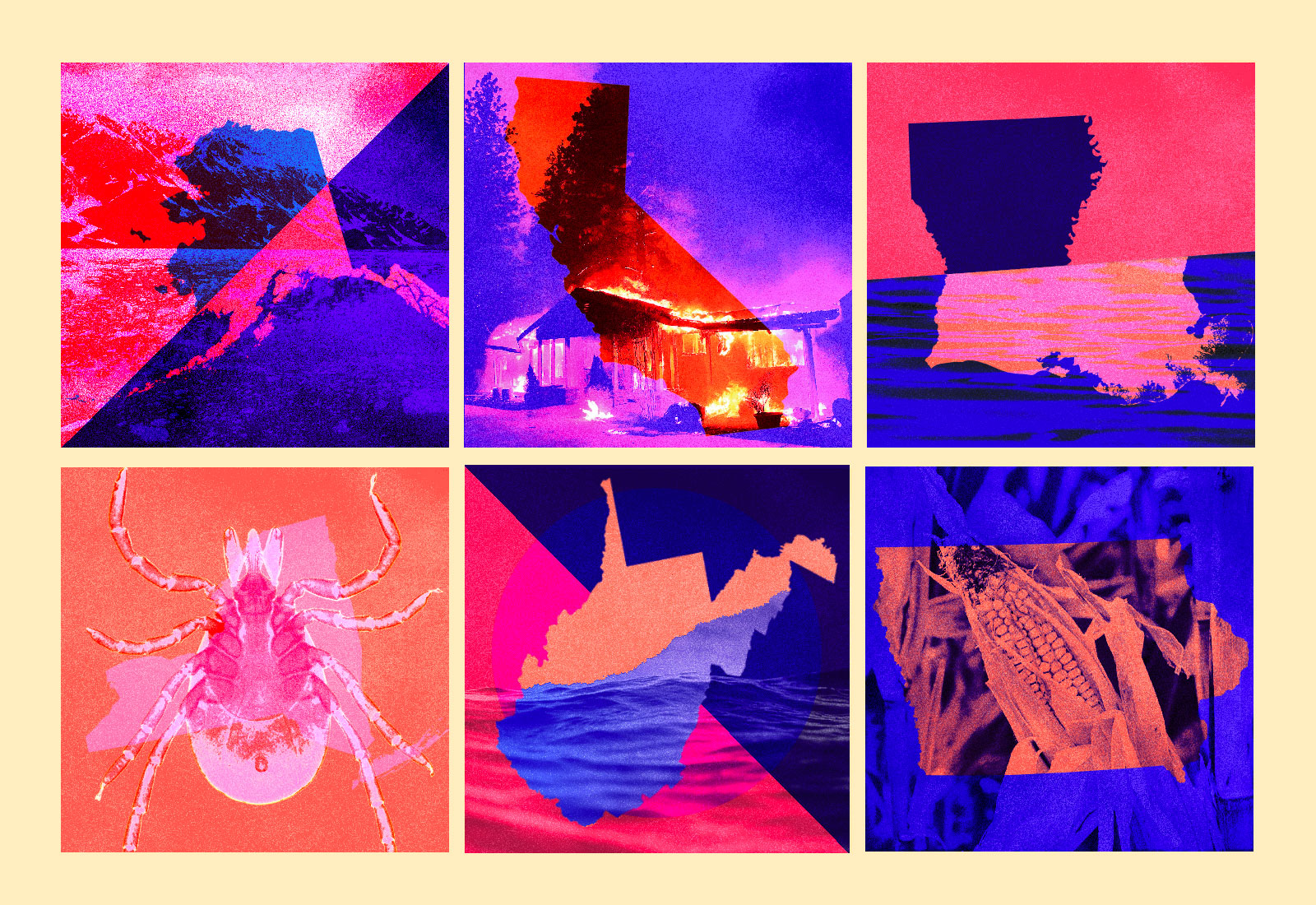

Each summer, the surefire signs of climate change come into sharper focus in the United States. Wildfires and heat waves plague the West. Increasingly intense hurricanes pummel the Southeast. Sudden thunderstorms soak towns from the Midwest to the mountains. Lyme disease-carrying ticks sicken hikers along the East Coast. And melting ice leads to more shipping pollution in Alaska. This barrage of headlines reminds us that these “extreme” events have already become our new normal as a result of the greenhouse gases accumulating in the atmosphere.

Taken one at a time, it’s possible to consume these occasional pieces of disaster coverage and still cling to the idea that climate change is happening somewhere else, to someone else. But listening to the growing chorus of people impacted by the changing climate rising up from all corners of the country forces us to recognize ourselves in our neighbors’ hopes and fears.

We have collected six audio stories from people all over the country who are already coping with the devastating consequences from climate change — in their own words.

Listen to their stories

Title

In Louisiana, back-to-back hurricanes leave no room to recover

Shonell Bacon

Lake Charles, Louisiana

Listen to her story

My name is Shonell Bacon. I’m originally from Baltimore, but I moved to Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 2001 to do my MFA program at McNeese State University here.

Every year from June 1st to November 30, we get fearful because half the year is worrying about when a hurricane is going to come. I keep a tab up for the National Hurricane Center all six months and I have a million apps on hurricanes and storms on my phones and tablets.

Currently, I live with my sister and my mom, and we were here for Laura and Delta. We were double hit because we had good ol’ Laura and then about 40 days later we had Delta. Those two events have been the most traumatizing moments of my life ever.

I will admit that during Laura, I was fairly sure we were going to die because it sounded like a thousand trains just going as fast as they can above you, beside you, behind you, below you. And it lasted for what felt like forever. We thought for sure the roof was going to rip off. But it didn’t. We were so surprised when we woke up the next morning, there was a roof.

As soon as day broke, my mom, my sister, and my brother went outside and they started calling for me. They’re like, “Come see.” And that’s when I broke, because I went outside and the house across the street from us had half a roof, and then the house next door to us, all the windows were busted out. I’m going to get emotional just because when I talk about this, there was such devastation, and I felt so horrible that we got saved when so many people didn’t.

This whole city was decimated. There are parts that will probably never come back, and if they do, I won’t be here because we’re already planning to be gone before the next hurricane season. I’m not Louisiana strong. I don’t know what they have in them to keep rebuilding, but I don’t have that.

In coal country, severe flooding tests the limits of regional resilience

Andy Waddell

Clay County, West Virginia

Listen to his story

My name is Andy Waddell, I’m a 40-year resident of Clay County, West Virginia, Appalachian Mountains.

Clay County is 342 square miles. We are a place of tall mountains and very narrow valleys. We enjoy four seasons. What we don’t enjoy is, we regularly have flooding.

We had a flood five years ago; we called it a “once in a lifetime, hundred-year flood.” That’s how we explained it away. I can remember that weathercasters were saying this could just be a real damnation. And in a matter of two hours of really heavy rainfall, everything went to pot — roads were covered, creeks were out of their banks, propane tanks were floating, cars were submerged.

We’ve had other storms here and, sure, we might lose electricity for a day or two. That’s common. But this wiped out the utilities. For many people, it was three weeks without electricity. I mean, the county shut down. People were standing there with all they owned in their arms. Everything else was washed away.

We are a resilient people. We’ve been through floods. We’ve been through disasters. And the truth is, we like it here. It’s beautiful. But for many people in this county, we don’t talk about climate change, period. The scariest part for me is, have we waited too long to make the necessary changes? If next summer, here comes another “hundred-year flood,” I don’t know if we can start over.

In Alaska, melting ice brings a boatload of new issues

Austin Ahmasuk

Nome, Alaska

Listen to his story

My name is Austin Ahmasuk. I was born and raised in Nome, Alaska, and I’ve been working as a tribal, environmental, and subsistence advocate here in my hometown since 1997.

Ways of life are changing here in the North very dramatically. A specific example was this last year during the first full moon in November. It’s a time when you can get out on land, access areas where ice isn’t terribly thick. And, for folks in the lower 48 that might not be able to understand cold, that’s always been a time in my life when river ice is generally two feet or more thick.

Well, this past year on the first full moon in November, river ice was barely six inches. Rivers which are normally frozen substantially, were mostly open. And so hunters like myself are contemplating the possibility that the animals that we consume for food — fish, wildlife, marine mammals — some of those animals may go extinct locally or shift their distribution north. And we may have to focus on other things that we’re not entirely used to.

These things are happening in the context of climate change. Absolutely. As another example, as waters have gotten warmer, shipping has increased. This past summer, communities in my region dealt with, for the very first time, trash from shipping-related activity washing ashore — plastics and petrochemicals and fishing gear. That month-long foreign debris event was very disturbing. We had to weed through trash to obtain things we need from the ocean. Those beaches are normally pristine.

And so we realized with this event, we’re totally on our own. We’re going to have to clean up our beaches ourselves and address this ourselves.

In Iowa, farmers adjust to more intense conditions

Meredith Nunnikhoven

Oskaloosa, Iowa

Listen to her story

My name is Meredith Nunnikhoven and I live in Oskaloosa, Iowa. I’m a fifth-generation farmer. We farm fresh, cut flowers and I just installed six acres of a chestnut plantation — so that’s the new diverse crop that I brought to the farm.

Iowa, we have floods, we have blizzards, we have tornadoes, we have the gamut of all this crazy weather, right? But what I’ve noticed is the intensity of it. It just seems like there’s more of everything. So if we have monsoon rains for three weeks, which is what we had two years ago, that affects everything that we do.

Normally we’re ready to plant at the end of April or early May, and we start working the ground. That goes for flowers, vegetables, and our crops. But the past several years, we’ve been very hesitant to put those crops in until we see these rains come through.

One year we had put in, I’d say, close to a thousand marigolds and several hundred tomato plants and peppers. Granted, those plants are pretty hardy, but I could visually see them outside getting intensely rained on for almost two and a half, three weeks. And we surely thought that they would die. And that makes us nervous now to put our crop in.

When I talked to my whole family, they all agreed: Climate change is real. We know it’s an issue and we’re trying to do everything we can here as farmers to combat that. We’re in it for the long haul. But for us to cover crop and start seeing improvement in our soils, that’s 10, sometimes 20, sometimes 30, if not longer, years until we would see those improvements from the adjustments that we’re making right now.

In California, the appeal of living near nature goes up in flames

Andrew Burke

Butte Creek Canyon, California

Listen to his story

Hello, my name is Andrew Burke and I’m a resident of Butte Creek Canyon, which was within the burn area of the California Camp Fire.

The Camp Fire was fast-moving. We heard, “Oh, it’s on the other side of Paradise. No big deal. Oh, it’s to Paradise. Uh oh, it’s halfway through Paradise. Oh, it’s completely through Paradise.” And we’re like, oh, wait a second. It’s only been half an hour. And as the crow flies, we’re not that far from Paradise. So, yeah, that’s when we really started hurrying hurrying hurrying to evacuate.

We packed up the back of the car. We helped my wife’s folks pack some picture boxes and stuff. I guess I didn’t mention that my wife was seven months pregnant at the time. So throughout this, we’re trying to keep stress levels down. And yeah, we scooted out.

We hit some traffic. You know, a lot of people got kind of stuck in traffic, but we made it through the fire burning down to where we were parked. We were kind of middle-of–the-road in how we were affected. I mean, we lost our home. We lost everything. Our whole community is gone. And that’s being middle-of-the-road in something like this.

When we came back to Butte Creek Canyon, it obviously didn’t look like anything we had ever seen. Everything was ash. Everything was charred. wWole trees were missing with just a hole in the ground where the roots were. I was just in awe. You knew there was a community here. You knew there were homes here and there was just nothing. It just didn’t look like a scene from Earth.

Even though it was really damaged. We decided to move back into the area, kind of within the burn scar — which is good and bad, because every day we have to look at the surroundings, take the kid on a stroller ride by our old home. But for the future, I hope that people are still able to live in these wild areas because they are nice places to live. On paper, this is a good place to raise a family.

We’re just going to have to learn to live with these fires and adapt. Just realize, OK. This is something that happens now.

In Upstate New York, warmer weather comes with a sickening bite

Emma Baker

Hudson Valley, New York

Listen to her story

My name is Emma Baker, and I am in Accord, New York, which is part of the Hudson Valley. I am a construction worker and landscape designer.

I’ve noticed changes in the environment since I grew up, even just walking around in the forest. I’ve noticed that the forests just don’t look as green and healthy as they used to when I was a kid. And, of course, there are way more ticks.

I do tick checks as soon as I get home and I try to pay attention. Other than that, I can’t change what I do for my work. That’s what I love to do. And it’s kind of inevitable that I’ll get bitten. Like just the other day when I was working, I found over 15 on me. I was like wading in tall grass and I found three on me at a time consistently for hours.

Generally I find them like on my legs first crawling up the ankles. If you have leg hair, it usually helps a little bit — you can feel them moving around better and you try to get them right when they’re crawling on you before they latch on.

I was bitten by a tick at some point in my 10th grade year in high school, and I got really, really sick. I didn’t know what it was from, because I never got a rash or anything. Usually if you get sick from a tick, especially if you’re going to contract Lyme disease, you get a bull’s eye rash, which is a red rash and like a circle around the area that you were bitten.

My main symptoms were, I had very, very severe headaches pretty much constantly; I was really sensitive to light; and I was really, really tired, like my energy level completely tanked. So that was pretty serious. I had a PICC line in my arm, which is like a little opening that they give you antibiotics through. You attach a syringe to it twice a day for a month. And the treatment did work. I was really lucky. I don’t think that I have long-term effects, although it’s kind of hard to know.

This story was reported by Emily Pontecorvo, Nathanael Johnson, Eve Andrews, and Zoya Teirstein. Teresa Chin led the art direction and produced the audio. Jacky Myint handled design and development. Edits by Katherine Bagley, Nikhil Swaminathan, and Matthew Craft.