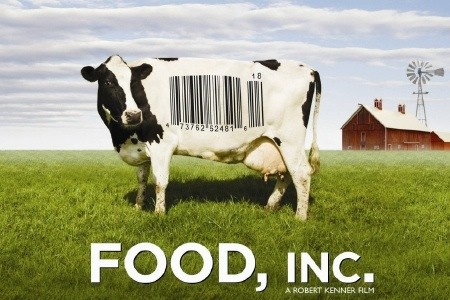

Food Inc. director Robert KennerRobert Kenner never set out to make a terrifying film when he started Food, Inc. But along the way, he found the food industry to be stunningly secretive–and what it’s hiding to be downright scary. The film shines a bright light on the handful of corporations that, behind a cloak of glitzy marketing campaigns, do the dirty work of putting cheap food on our plates. As Variety put it, the film “does for the supermarket what Jaws did for the beach.” Not long after the film opened nationwide, I caught up with Kenner by phone from his Los Angeles home.

Food Inc. director Robert KennerRobert Kenner never set out to make a terrifying film when he started Food, Inc. But along the way, he found the food industry to be stunningly secretive–and what it’s hiding to be downright scary. The film shines a bright light on the handful of corporations that, behind a cloak of glitzy marketing campaigns, do the dirty work of putting cheap food on our plates. As Variety put it, the film “does for the supermarket what Jaws did for the beach.” Not long after the film opened nationwide, I caught up with Kenner by phone from his Los Angeles home.

———————–

Kinge: As I watched your depicton of conventional farmers in the film, the word I kept thinking of was “sharecropper.” For example, individual farmers no longer legally own their own seeds; they must purchase them from biotech giants like Monsanto, and essentially they remain in debt.

Kenner: You know, I don’t even talk about in the film whether GMOs are good for us or bad for us. But what I find so amazing is Monsanto saying we can’t feed the world without [their genetically modified seeds], but then they’ll do everything possible to stop you from knowing they’re in your food…. [and] if your seeds are so good, why do you have to put seed cleaners out of business? Why can’t we have a free market? Why do these farmers have to be sued? Shouldn’t your product speak for itself? And it’s the power of this corporation to sort of attempt to both patent and dominate this industry that I find of concern. What we tried to do in this film was to create a dialogue about how we eat. And these corporations that didn’t want to talk to me in the film, many of them, like Monsanto, go to great lengths to get their message out, but I feel their response is a misleading response. But I’m heartened that there are a number of other companies who have said, “we recognize the great success of this film and we think there should be a conversation.”…Troy Roush is sort of an industry farmer, who uses Monsanto products and will defend them on certain levels, though he’s also been sued by them, and from his point of view for no cause whatsoever, and it cost him almost half a million dollars to defend himself. Troy was saying that he thinks 95% of farmers in America would like the film and agree with it, but they just need to see it.

There seem to be a lot of similarities between the historic cloaking of information by the tobacco industry and the cloaking of information by the agribusiness industry today.

You know what it is? It’s that the world has been transformed without us knowing about it and these companies don’t want you to thinking about this food. They want that Orwellian myth that it comes from a small farm with a white picket fence and a red barn when in reality our food comes from giant factories. It’s become industrialized, but it’s not only the chicken and the cow, it’s the tomato and the lettuce. We’re basically eating food with far fewer nutrients, and it’s not healthy. But it’s more than that. We’re also being denied the right to know what’s in it, so it’s connecting the dots to the system. And ultimately, I’m optimistic, and when we learned about tobacco … a few very powerful corporations that had great connections to government and they were financing studies about how their product was not bad for you, and then when we finally found out that this was a total falsehood. And I think when we start to find out about this food is doing to us, we’re going to change how the food industry works as well…If we live in a free society and we want to make choices, choice has to be made based on information, and what lengths they’ll go to stop you from having that information…So we don’t know if there’s cloned meat, we don’t know if there’s GMOs, we don’t know if there’s rBST. I’m not even saying whether [genetic modification] is good or bad. I’m just saying, if it is good, why wouldn’t you want to advertise it?

With the new federal regulation of tobacco, there is expected to be a lot more transparency around the tobacco industry, but the federal government has always regulated agriculture and yet, as evidenced in your film, there has been little transparency thus far around how food is produced. Do you expect that to change under Obama?

Well, one thing [happening] is that it looks like this year the FDA will pass regulation that will [remove] food that sits on the shelf that makes us sick – that has E Coli 0157:H7. So unfortunately a lot of these acts still are in favor of large business. On one hand they’ll help protect us, on the other hand they keep regulating in favor of large corporations. So I would just say to consumers, whenever possible, get to farmer’s markets, support local farmers, I would also say eat organic. Even if we change just one meal a day, we’re going to start to improve the system. We’re going to vote three times a day with breakfast lunch and dinner but we also have to vote with out votes. Unfortunately right now we’re subsidizing food that makes us sick, and if we can create enough of a movement, I think we can change the farm bill to the food bill.

You screened the film for Tom Vilsack, the secretary of the US Department of Agriculture. He’s been a supporter of genetically modified foods. How did he respond?

You screened the film for Tom Vilsack, the secretary of the US Department of Agriculture. He’s been a supporter of genetically modified foods. How did he respond?

Well, he’s a governor from the biggest corn state in the country and he basically was a Democrat from a Republican state. But ya’ know I can only quote Michael Pollan in this, saying that Vilsack turned out to be much more open to hearing and listening. So I do think he’s sincere, but I also think, as he says that if this movement keeps growing, he will have to listen, if it doesn’t nothing’s going to change. Certain things will change because you can’t have healthcare reform in this country without changing the food system, so they are going to be forced to change things, whether they like it or not. But hopefully as a food movement, we can help force it to change faster.

In the film you show that several FDA officials have strong ties to agribusiness giants, calling it a sort of “revolving door” between government and corporate agriculture.

Well, to begin with, we’re not opposed to people going from industry to government. I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing for people who know an industry to go into government to help regulate it. The problem is when they start to rule on things that they have done in industry and then they go back to industry with big raises. There seems to be a certain level of conflict. And it’s a pattern that’s taken over Washington. I think these things die hard and all I would say is I think we have to start supporting and doing everything we can for small farmers. It’s much easier to try to put in legislation for safe foods, but basically it’s designed for big corporations, and sometimes it makes it harder for the small farmers, and I think it’s going to better for us and our communities and our health if we can support the smaller farmers. And that’s not going to be the first instinct in Washington because that’s not the way it works. But I think it’s that we as consumers have to start to flex our muscles…to help level the playing field so that we support food that’s good for us.

A good portion of the film focuses on the dichotomy of cheap food versus expensive healthcare: subsidized crops make certain foods dirt-cheap at the check-out counter or fast food window but wreak havoc on human health and put families into debt.

[That subsidized corn and soy not only goes into hundreds of food products, but it also acts as cheap feed for livestock]. So basically you now bring this artificially inexpensive corn to these feedlots. And when [a small farmer] grows corn on their own property and is not getting a government subsidy you can’t then feed his food to these animals and be in competition to these mega-corporations. So we’re subsidizing food that ultimately turns into sugar in our bodies, and all of a sudden, we’re getting massive amounts of sugar, because of the corn and soy, and that sugar is making us fat.

The film very briefly touches on herbicide and pesticide chemical runoff finding its way into waterways and also mentions that increased cattle grazing has led to deforestation in, for example, the Amazon. But it leaves it at that. Was it a conscious choice to keep the environmental impacts brief?

We could have gone on about the environment. Ultimately, food accounts for a little over 20-25% of our carbon footprint. Like health reform, you can’t have environmental reform without changing the system and what I realized in making this film – perhaps it’s obvious but for me it really hit me – is that this is an unsustainable system. It’s a brand new system. We’ve had agricultural for ten thousand years. This system is about 40, 50 years old. And it’s not working for two giant reasons. It’s based on gasoline, which is a diminishing [resource] and as it starts to run out and as its prices start to get up to those historic highs, we’re going to have very expensive food. It takes so much gasoline to grow and transport this food. Also, there is so much pollution involved with this system; we’re depleting, poisoning the soil, the riverways, the oceans. So there are many things we don’t hit on entirely in the film, but basically what the film is about is connecting the dots to show you that this industrial system is not working.