To certain vegans — the sort who recently saw fit to flay a chef who supports small farmers in the middle of Iowa (see comments below Kurt Michael Friese’s wonderful piece in Grist) — Fergus Henderson will be an object of derision.

Feeling "a little dented”? Henderson would prescribe a bit of a dish he calls "rolled pig spleen" — not endearing advice for those who worship at the altar of soy (and demand that you do, too).

Yet in terms of promoting a truly sustainable food culture, Henderson — owner of St. John restaurant, just outside of London’s famed Smithfield meat market, and author of The Whole Beast — may be the most important chef alive today.

Last week, Henderson appeared in New York City to promote his new cookbook, Beyond Nose to Tail. When I learned that Savoy, owned by pioneering farmers-market forager Peter Hoffman, would be hosting a dinner honoring Henderson, I immediately began hectoring my Grist editor to send me up to the big city to cover the event.

To my delight, she agreed. And here is what I saw (and tasted).

First, let’s get to the case for Henderson as an unlikely green hero. It goes like this:

If we are going to feed a growing global population with small-scale, local-oriented agriculture, then we’re going to need to keep livestock, which boost farm productivity by turning food scraps and inedible (by humans) plant matter like grass into high-quality, soil-building fertilizer as well as nutrient-rich food.

And if we’re going to eat those livestock in a way that’s sustainable, then we not only have to cut down on how much meat we eat, but we also have relearn the near-forgotten art of enjoying the whole animal: spleens, livers, hearts, and other stuff that people now think of as the "nasty bits" when they think of them at all.

In short, to quote a famous line from The Whole Beast, we have to rediscover the "set of delights, textural and flavorsome, that lie beyond the fillet." It is Henderson’s singular achievement to have turned "nose-to-tail" eating, traditionally a pleasure enjoyed by people of limited means, into a culinary fashion statement.

But it’s more than just a fashion statement. By rediscovering the genius of offal, eaters revalue animal parts that small-scale, pasture-based farmers typically throw away for lack of a market. Paying a fair price for offal from carefully raised animals helps keep ecologically minded farmers on the land.

OK, I’ll let the vegans chew on that. On to dinner!

Savoy is located in a pretty old brick building in Manhattan’s NoLita (north of Little Italy) section. When chef/owner Peter Hoffman opened it in the early 1990s, the neighborhood crawled with wise guys, junkies, and old Italian ladies. Today, it’s the province of models and funders (of both the hedge and trust sort).

Through its journey from grit to glitz, NoLita has always retained an artist-pioneer feel — an aspect for which Savoy feels like one of the last vital repositories. Long before local became fashionable in New York, Hoffman was running Savoy as a kind of east coast version of Chez Panisse — to quote the Savoy website, "to create delicious and memorable meals by sourcing the best ingredients possible from chefs we know, and then augment those flavors with a straightforward cooking style."

I arrived at Savoy on a cool, wet fall night, excited about the meal but a bit nervous about dining solo at a busy Manhattan restaurant. The meal had been sold out days in advance; a stylish crowd queued up outside, looking in for glimpses of the celebrated chef.

Soon enough, I was whisked upstairs and dispatched to a table full of people who quickly put me at ease. To my left sat two women with a strong connection to farming: Irene Hamburger and Nena Johnson of Stone Barns, the sustainable-ag project in Westchester County.

Across sat the legendary restaurant critic and food writer Mimi Sheraton, along with her husband, a charming gentleman who grew up in the Italian sections of both the Bronx and Manhattan in the 1940s. And to my right was the architect Larry Bogdanow, who designed Savoy and is a ravenous reader of food-politics books.

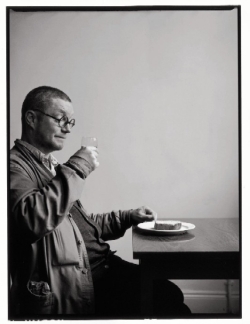

Before I knew it, I was sitting among new best friends, the first course was coming, and Fergus Henderson himself was walking around looking arty and British and embarrassed by the attention. He wore crisp cook’s whites, close-cropped hair, a striped apron, and eccentric round-lensed glasses that reminded you that he was trained as an architect. Altogether a teddy bear of a man, with a slightly mischievous face worthy of the smart, quietly hilarious prose found in his books.

Each of the meal’s five courses was lifted directly from Henderson’s new book, Beyond Nose to Tail. Unlike its predecessor The Whole Beast, Beyond offers few shockers on the order of "rolled pig’s spleen" or "lamb’s brains on toast."

Rather, it tends to integrate offal into simple, balanced, and delicious preparations featuring a variety of seasonal vegetables.

As we gaily munched the appetizer of crispy deep-fried, battered rabbit legs (quiet, vegans) and "little anchovy buns" — small, olive-oil-redolent rolls stuffed with garlicky anchovy paste — Hoffman addressed the room with a brief, eloquent account of how he’d known Henderson for years and the importance of eating the whole animal.

Then it was Henderson’s turn. Speaking softly and shyly in a gentle British accent, he declared he felt "a bit cheeky" to be in chef’s whites, given that he’d spent the day "doing the sort of things one does when one releases a book, and not cooking in the kitchen." Still, he knew he could trust his recipes in Peter Hoffman’s hands, and bid us an enjoyable meal. The audience erupted in cheers.

Nobody found Henderson even a bit cheeky for not cooking. Most of us knew that he’d been battling Parkinson’s for years, and not spending much time in restaurant kitchens.

After the appetizer, out came a dish playing sweet lima beans and thin slices of meaty ox tongue against a green sauce piquant with parsley and anchovies, all napped with a delicate broth.

Next came a plate that would have silenced the vegans for a few seconds, until they discovered the taboo presence of crème fraîche: a raw salad of grated beets, red onions, and cabbage, those deep reds offset by a smattering of coarse-chopped, bright-green chervil. The dollop of crème fraîche, when it mingled with the beets, gave the impression of an impossibly fresh borscht. Bravo.

That prepared us for the meal’s highlight: a delicious concoction featuring snails, trotters (slow-cooked pig’s feet), spicy chorizo, and chickpeas, all napped in a deep-flavored, meaty broth. At the center, absorbing and concentrating those flavors sat a piece of toasted bread. All of these elements came together into a kind of peppery, deep-flavored study in various textures that occasionally stopped conversation among the hardened gourmands that surrounded me, eliciting low and heartfelt "ahhhs."

Finally, there was a creamy and delectable apple and Calvados trifle, and I was back out into the New York night, fortified by great food and and the jolt of having made new friends.