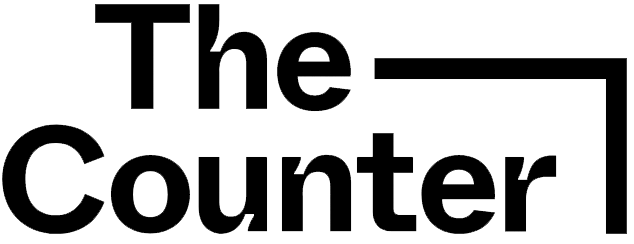

This month, health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and agriculture secretary Brooke Rollins unveiled updated national dietary guidelines in a surprising new visual: an inverted food pyramid, with the widest section teetering at the top. At the very bottom, a tiny amount of whole grains are represented. The rest of the new food pyramid is split in two, with protein, dairy, and “healthy fats” dominating the left side, and vegetables and fruits taking the right.

The gist of the new guidelines, which have been brandished as part of the Make America Healthy Again campaign led by Kennedy, is to prioritize nutrient-dense whole foods, avoid highly processed foods, and eat more protein. Fairly uncontroversial guidance under the tagline “Eat real food,” like avoiding added sugars, salt, and chemical additives, has been received positively by nutrition experts.

But protein appears to occupy a vexing space within the new guidelines. Kennedy and the committee of nutritional experts who consulted on the guidelines — at least four of whom have ties to meat and dairy industry groups — have been roundly criticized for encouraging Americans to eat more protein and dairy. Organizations like the American Heart Association say that consuming too much saturated fat, which is found in animal protein sources like beef and full-fat dairy, can be linked to cardiovascular problems.

In addition to the health concerns related to a meat-heavy diet, the imperative to eat more meat and dairy comes with heavy environmental and climate considerations. There is simply no way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to reach targets set by the Paris climate agreement without also lowering emissions from the food system, which is driven by livestock and seafood production.

Sam Kass, a former chef and nutrition advisor to President and First Lady Obama, spoke to Grist about the new inverted food pyramid, which he calls an “ecological disaster,” and what conscientious eaters can do about it. Kass is also the author of The Last Supper: How to Overcome the Coming Food Crisis and currently a partner at Acre, a venture capital firm with a focus on food systems. The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. I wanted to start by asking your initial reactions to the updated dietary guidelines. What stood out to you when you first heard the news?

A. I think that these guidelines represent a really troubling pattern from the secretary of Health and Human Services in the way that the agency is making policies that affect the lives of hundreds of millions of Americans. Like other things they do, there are some superficial good things in the dietary guidelines, like “Eat real food,” which is a nice slogan. It may not really mean much to an average person. But I support that sentiment, in the spirit of Michael Pollan — although he would go on to say, “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” I also think some of the dietary guideline’s language around avoiding ultra-processed foods is positive.

One less important part that I found distasteful was the narrative that, for the first time in history, the government has said you shouldn’t eat processed foods, which is just demonstrably false. It was as if HHS was responding to the food pyramid of the 1990s and pretending that the last 20 years hadn’t happened.

The reality is they made two substantive changes. First, they got rid of My Plate, which is a real mistake. It was a fundamentally better symbol and tool to help people actually visualize what their plates should look like. The only other change when you actually get underneath it is that it is ideology- and influencer-led policy-making as opposed to science-based. Four out of nine members on the panel of experts brought in to consult on the new dietary guidelines have ties to the meat and dairy industries. The new food pyramid is promoting meat and cooking with butter and beef tallow, but the guidance itself is unchanged.

HHS maintains that saturated fat should be no more than 10 percent of your daily calories. So what they’re promoting and what the guidance is are in direct contradiction. If you’re keeping your calories at 10 percent from saturated fat, and you’re cooking your eggs in butter, then how are you going to fit in the steak and the cheese and the beef tallow? It doesn’t make any sense.

Q. What are the climate implications of encouraging people to eat more meat and dairy?

A. From a climate and sustainability standpoint, this inverted pyramid is an ecological disaster. They’re trying to drive consumption of the part of the food ecosystem that is by far and away the number one driver of environmental degradation and emissions from the food and agricultural systems. And that’s true both here in the U.S. and around the world. Beef is the number one driver of deforestation and land use change in the world. And it’s just downright irresponsible to not be taking into account our ability to feed ourselves in the future when it comes to the guidelines we’re putting out today.

This administration, talking about making America healthy, has systematically undone every piece of climate rule and policy that they possibly can. They’ve withdrawn all investment in resiliency and adaptation and decarbonizing our food system. It’s clear when you look at the data that the number one threat to human health is climate change. The idea that somehow you can proclaim to make America healthy again, and totally gut our ability to mitigate the worst of climate change is just as deep a contradiction as there is.

Q. What do you think is missing from the administration’s embrace of eating “real food”?

A. I think that part on its face is generally fine. If they were promoting that as the cornerstone of your diet, then it would be fine. The problem is the meat agenda. The U.S. is continually top 10 in global per capita consumption of an animal based protein.

But the message to eat less processed food is good. We were giving the same messages in a slightly different way during the Obama administration, and things have evolved a lot in 15 years.

Anna Moneymaker / Getty Images

Q. I wonder if you could talk more about your work during the Obama administration. Why do you think MyPlate.gov (which now redirects to more information on the new guidelines) was a better visual tool to communicate the nation’s dietary guidelines than the new inverted food pyramid?

A. We undertook a very serious process to overhaul the way that these guidelines were communicated and the symbol that we used to try to help people make better choices. You need to give some people tools in a way that meets them where they are. It’s fine to tell everybody to eat a bunch of steak and salmon and fruits and vegetables, but for so many Americans, those literally don’t exist around them or they can’t afford it. So the reality is a lot of what they’re eating is coming in a package.

How do you navigate that? We worked very hard with design firms to come up with different symbols and ways to communicate this information that would help be a guide. And the plate came out as by far and away the most useful symbol. People would visualize: When I’m making my plate, half of it should be fruits and vegetables, a quarter of it should be whole grains and then a quarter should be protein. At any given moment, the inverted food pyramid doesn’t help you decide what a balanced meal looks like.

Q. What’s one thing consumers could do differently to mitigate our impact on the environment and climate?

A. The thing that’s by far the most impactful thing to do from a climate standpoint is eat less meat. I mean not even close, there’s nothing else close. That is still the best thing you can do.

Q. Your book, The Last Supper, revolves around the question: How do we grow more food while minimizing our environmental impact? And this whole conversation I’ve been thinking about beans. Do you think legumes and other plant-based sources of protein have a fighting chance with consumers?

A. I sure hope so. Beans are kind of the magic food. They’re as nutrient-dense a food as you can eat. They are super cheap. They’re so delicious. And they’re great for the environment, so they check every box. I think people are working on how to make beans sexy; it’s something I’ve done a lot on over the years. We’ve just got to put some more love into it.