Photo: Matthew KronsbergCross-posted from Gilt Taste.

For many small farmers, the time from late August until the first frost is like the stretch between Thanksgiving and Christmas for retailers: It’s when the year is made or broken. It’s when all the expenses of the spring and summer — paying the workers who plant and pick and weed, purchasing seed and feed and fuel — are finally paid for with those flats of tomatoes and bushels of zucchini you see piled high on market tables. That late summer crop is damn near the whole ballgame.

This is the great risk of farming: It all hangs on the harvest. Without that, calamity.

Calamity came to Kira Kinney, Ray Bradley, and thousands of other northeastern farmers flooded by Hurricane Irene late this August. Their stories are quickly becoming well known through pieces in The New York Times, and wrenching videos from Food Curated and The Perennial Plate. They remind us not only of the vulnerability of small farms, but also of how critical it is that the communities that support them in good times remain there in bad, and that these bad times go on long after we’ve forgotten this latest tragedy.

Kinney and Bradley both have stands at Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza Farmers’ Market; they farm in New Paltz, N.Y., about 90 miles north of New York City. It was there that the Wallkill river overflowed its banks, rapidly inundating both farms. What was ripe, or nearly so, was hastily picked. Of the crops left in the fields, more than 90 percent drowned.

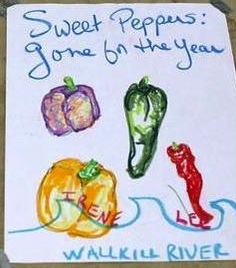

Photo: Matthew KronsbergThe Saturday after the storm, both growers set up at the market as usual, bringing what they could rescue from the rising water. There were heirloom tomatoes of every shape, size, and color, along with squash, beans, and okra. Kira had eggs and Ray had pork. Were it not for the donation jar on Ray’s table and the note on Kira’s, it would have been easy to think that they’d weathered the storm without incident.

Photo: Matthew KronsbergThe Saturday after the storm, both growers set up at the market as usual, bringing what they could rescue from the rising water. There were heirloom tomatoes of every shape, size, and color, along with squash, beans, and okra. Kira had eggs and Ray had pork. Were it not for the donation jar on Ray’s table and the note on Kira’s, it would have been easy to think that they’d weathered the storm without incident.

But if you took a moment to read Kira’s note, this is what you would have learned: ” … The farm is fine in terms of people, animals, and structures. That is good to be able to say, considering how much some other people I know have lost. The real problem is that 19 out of 22 acres that were planted all went under water — really under water … Ray Bradley told me that he had canoed over that field and that the water was up to the eaves on the old barn that sits at the edge of the field … There are a lot of tough decisions that I am faced with making right now — I have to cut staffing or at least pull back severely on everyone’s hours, I cancelled my cover crop seed order for the fall, I will be switching my chickens off of organic feed when we run out of what I currently have on hand. I will till under a season’s worth of hard work and hope.”

Photo: Matthew Kronsberg As the depth of the crisis sunk in, customers and fellow vendors mobilized. What started as chitchat at the market about the flood — ironically, at the fish stand — turned into an email list of concerned customers looking for a way to help. By the afternoon, Blue Moon Fish was organizing a benefit concert for its neighboring farm vendors, to be held in November. Greg Lebak, a flower farmer who lost over $100,000 worth of peonies to the storm, gave broccoli to Kinney and Bradley to sell at their produce stands to help offset their losses in some small way. Some customers at the market blurred the line between shopping and donating, offering up the occasional “I’ll give you $20 for this cabbage,” and maintaining a veneer of business as usual.

Photo: Matthew Kronsberg As the depth of the crisis sunk in, customers and fellow vendors mobilized. What started as chitchat at the market about the flood — ironically, at the fish stand — turned into an email list of concerned customers looking for a way to help. By the afternoon, Blue Moon Fish was organizing a benefit concert for its neighboring farm vendors, to be held in November. Greg Lebak, a flower farmer who lost over $100,000 worth of peonies to the storm, gave broccoli to Kinney and Bradley to sell at their produce stands to help offset their losses in some small way. Some customers at the market blurred the line between shopping and donating, offering up the occasional “I’ll give you $20 for this cabbage,” and maintaining a veneer of business as usual.

This veneer is important. Farmers are providers; justifiably proud people. This is not the sort of attention or support they crave. They’ll survive this year by looking to the next, trying to keep the appearance of normalcy in a situation that is anything but normal.

Ray still had his eighth annual Farm Fest one recent Sunday; there was more barbeque and beer and banana pudding than the assembled guests could ever have consumed. A bluegrass band jammed under a battered maple tree, but the hayride took kids along paths still ankle deep with mud, past brown, sodden fields. The summer vegetables that had filled platters in years past were largely absent this year. It was, in a small way, like the first Mardi Gras after Hurricane Katrina; simultaneously a distraction from, and a display of, all that had befallen the area.

Thankfully, Bradley’s farm will survive, but it will take him years to make up for these losses. He will continue to go to the market through the winter, selling pork, honey, and his peerless paprika.

Photo: Matthew KronsbergKira is less certain about her winter plans, but has tried to be creative, and hopefully effective, in finding ways to generate enough cash to get her through the season and into shape for spring planting.

She’s offering a “Market CSA,” basically allowing customers to buy $110 worth of produce in the future for $100 now. Laying bare the details of her business, she also created a registry that itemizes her main expenses and offers opportunities for donations. It’s full of things most consumers never think about: $4,000 in fuel to heat her greenhouses through the winter; $10,000 for soil and planters to start the spring crops, and another $1,200 for nitrogen-building rye and vetch cover crops. (For the home gardener, her list of seed providers is bound to bring a new source or three into the mix.)

Kinney’s request for $4,500 worth of organic chicken feed caught the attention of Francine Stephens, an owner of Brooklyn’s always-thronged restaurant Franny’s. “We rely very heavily on Kira,” she says. “She has the best eggs in the world.” And so regular restaurant customers of Kinney’s, like Franny’s and Rose Water, have bought in. But so, too, have some restaurants outside of her usual client base, like Jimmy’s No. 43. Jimmy buys his produce at a different market. His path and Kira’s don’t cross. But they met at a greenmarket association meeting after the storm, and Jimmy pulled out his checkbook, taking a serious chunk of cash out of circulation for the better part of a year. It’ll help buy Kira supplies, but this sense of pulling together also provides a morale-boosting shot of faith.

Next summer, assuming they’re spared further catastrophe,

Ray and Kira’s tables may be brimming again with greens and eggplant and squash. They will banter and joke with customers and their fellow farmers. People will complain about the prices of eggs and of tomatoes, and then buy them anyway because they know they’re worth it.

But these farmers, and many like them, will have known calamity. They will be walking wounded for a very long time, carrying debt and fear. If — when — we see them come back with their trucks full, we should not, even for a second, mistake the resiliency we see in them for the good fortune they deserve. We know their risks. Let them know someone is there for them.

How you can help

- Visit Kira’s registry or Ray’s donation page and make a direct contribution.

- GrowNYC is collecting money for affected farms throughout New York State.

- Vermont farms can be helped through the Northeast Organic Farming Association’s relief page.