Bram Ahmadi, founder of both People’s Grocery and People’s Community Market.

Brahm Ahmadi spends a lot of time thinking about something most people take for granted: grocery stores.

But it hasn’t always been this way. As one of the founders of the nonprofit People’s Grocery in West Oakland — the Bay Area’s most notorious food desert — he and his colleagues started out with more affordable, less ambitious projects, like a mobile food delivery service and a local community-supported agriculture (CSA) box. But it quickly became clear — as several grocery chains tried to enter the neighborhood and failed, and residents were left relying on corner stores or taking long trips by public transportation to other neighborhoods — that the area needed a reliable, independent grocery store.

“Residents said, ‘What you’ve brought to the neighborhood is great, but it’s far from a complete solution,’” Ahmadi recalls.

So, he left People’s Grocery, spent time in business school where he became an expert on community grocery stores, and then secured a possible matching loan from the California FreshWorks Fund for around a third of the funding. Ahmadi then hatched a plan to raise the remaining $1.2 million needed to start the People’s Community Market through what’s called a direct public offering. In other words, he’s inviting California residents to invest in fresh food — literally. For a mere $1,000, anyone in the state can become a shareholder.

As focused as Ahmadi is on getting this project funded — and he is, very — he’s also well aware that grocery stores are only one piece of the puzzle in a neighborhood where fresh food is hard to come by and 48 percent of residents are obese or overweight.

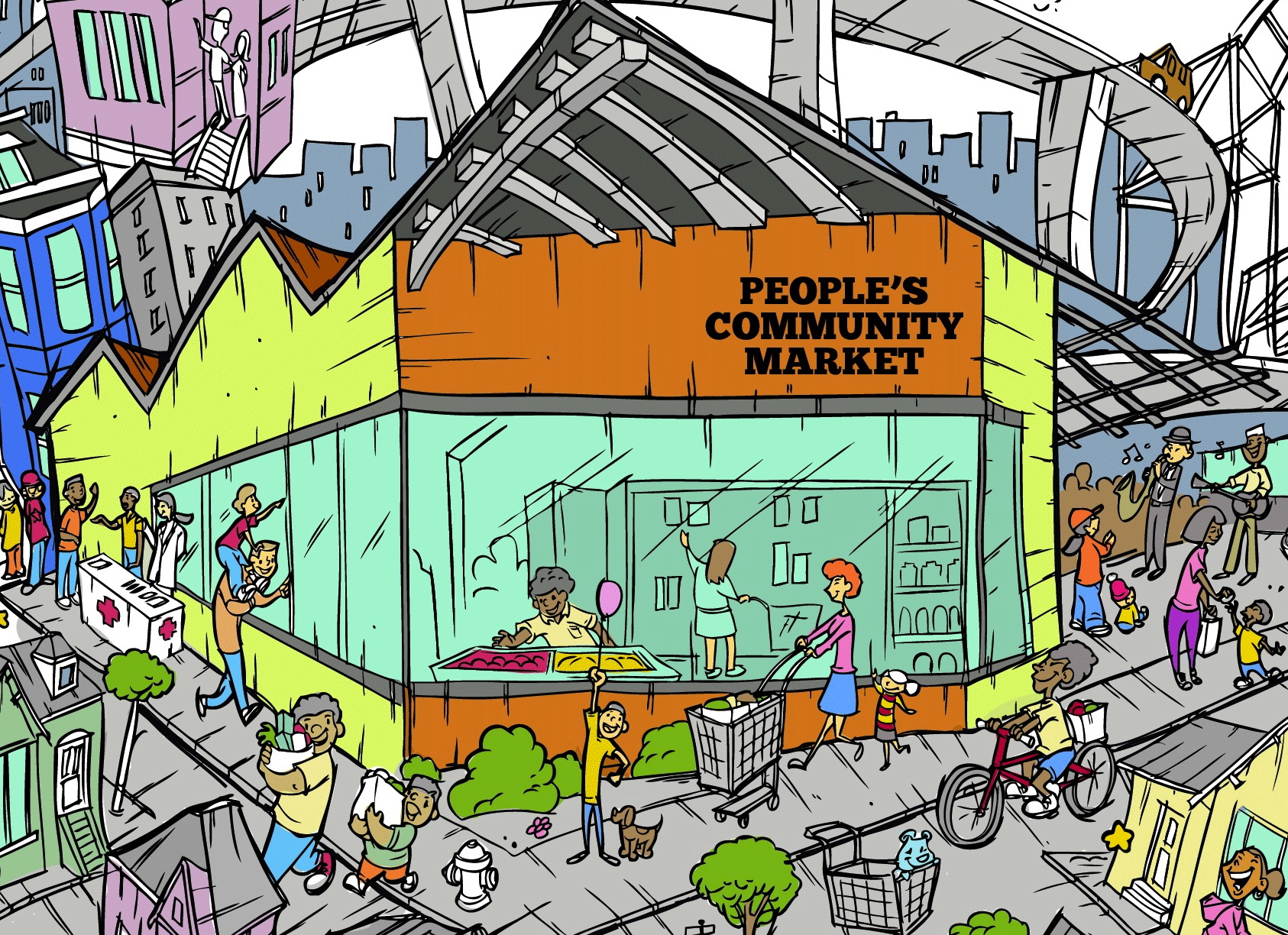

A rendering of the planned People’s Community Market in West Oakland, Calif.

“Education and access are two sides of the same coin,” says Ahmadi. “You can’t make healthy food available and just expect people to buy it. We’ve never thought that would work, we’ve never seen that work. And it’s not a very successful strategy to support people becoming more knowledgeable about their dietary choices without having a built environment that supports a change.”

That’s where the relationship between People’s Grocery and other community organizations come into it. Ahmadi envisions nutrition counselors on-site in the store offering advice, classes, and health screening. “We consider the education and health support service element to be core to the business model, not peripheral,” he says.

And that’s not the only way the People’s Community Market will differentiate from other, larger grocery stores. With a community advisory council (a group of neighborhood folks who will advise on things like planning, outreach, marketing, and recruitment), a commitment to hiring at least 50 percent West Oakland residents, and an eye toward community participation at every turn, Ahmadi hopes the market will succeed where bigger chains have failed.

While a cool grocery store will no doubt put the neighborhood at increased risk of gentrification, Ahmadi says, that fact simply can’t be a seen as a deterrent.

“Does that mean that out of your fear of [gentrification] you leave the community in the condition it’s in?” he asks. “That’s just not a very good a choice for us. Gentrification is a reality that goes far beyond what we’re doing here.”

Ahmadi also points to other examples of independent groceries in food deserts, such as Detroit’s Metro FoodLand, and the ways they have used community investment to stay viable in a market that’s less hospitable to chains like Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods. As Ahmadi tells it, Metro FoodLand owner James Hooks bought the store from Kroger when the chain decided to close all its Detroit stores.

“For the first few years after Hooks took over, the shrinkage [i.e. theft] and employee turnover were both really high,” says Ahmadi. (The average grocery store suffers from 3 to 5 percent shrinkage.) So Hooks started to do what only a small, independent grocer can — he got to know his workers and his customers. “He reformed his employee policies — to treat his workers better and give them more meaning. He also focused on relationship-building with the customers, and reformulated his products based on what they asked for … and as a result, he has dramatically reduced those numbers.” These differences — while the may seem small — have kept Metro FoodLand in business in a neighborhood where Kroger couldn’t survive.

“There’s a lot of research that shows that larger chain stores are not well suited for these types of demographics. They don’t have the ability to customize because they’re so centralized,” Ahmadi says. For instance, West Oakland shoppers aren’t likely to spend all their grocery money all at once, but they shop often, spending around $20 at a time. So Ahmadi plans to build a store that is smaller than the average supermarket, with less overhead and around 40 percent fewer items in stock.

“If I was an executive at a major chain, beholden to my shareholders, and needing to maintain large profit margins, I probably would say don’t open a store in West Oakland,” Ahmadi says.

Of course, if all goes well, the People’s Community Market will have shareholders, too — just a different kind.

“We’re trying to create an exciting proposition that offers a shift away from Wall Street. We hope our investors will also be proud allies and supporters who care about impacting our mission,” says Ahmadi.

Not that there isn’t money involved, of course. In fact, according to a study conducted by the People’s Community Market, around 70 percent of West Oakland residents’ grocery spending — or $58 million a year — is currently being spent out of the neighborhood. Ahmadi says he hopes to absorb around $10 million in gross sales, by serving, and employing, a significant portion of the community.

“We need a new kind of model for food deserts,” says Ahmadi. “I believe it can work — but it takes a lot more work.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the loan from California FreshWorks Fund as a grant.