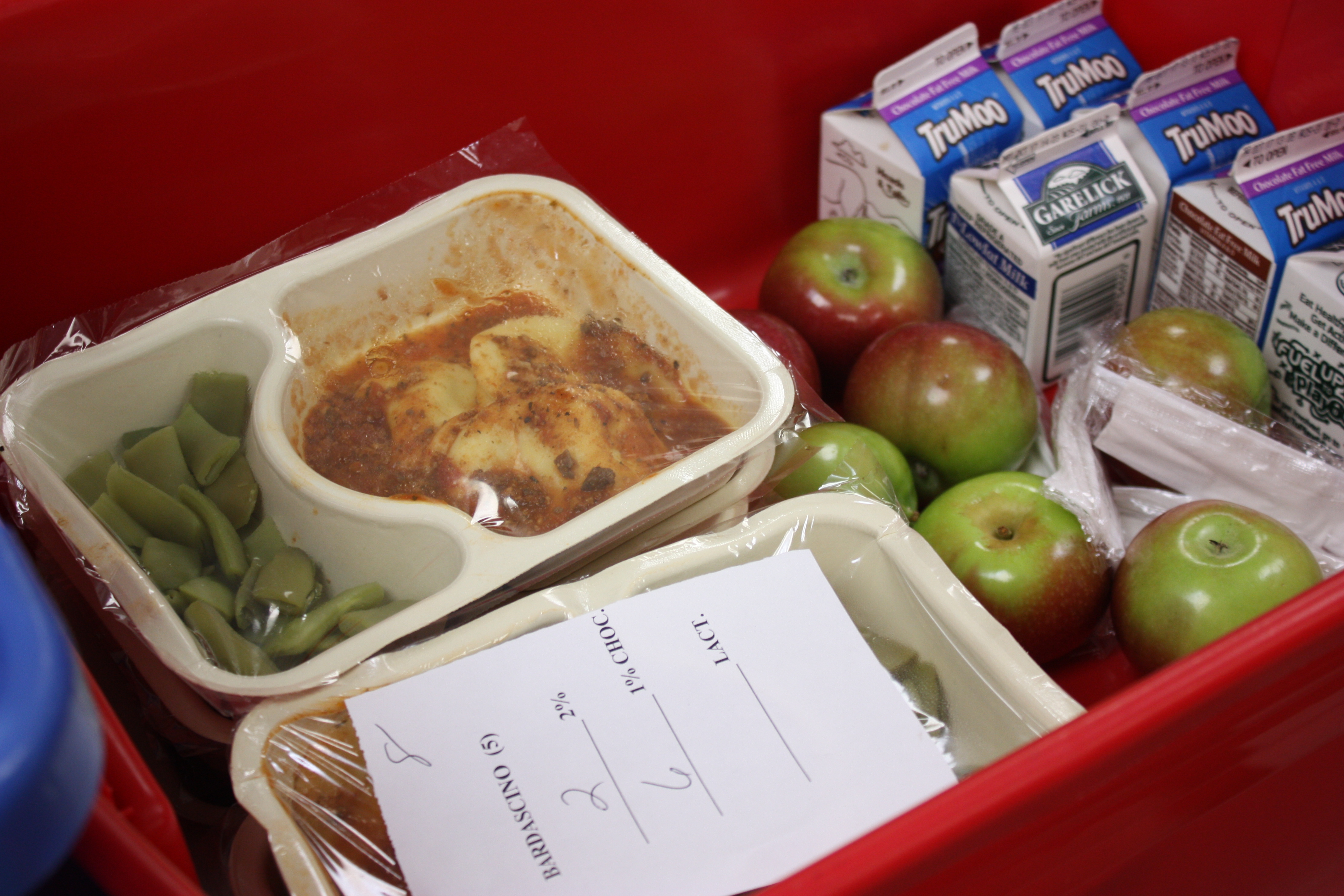

Right now Republicans, Democrats, and the First Lady are slugging it out over a proposal to weaken the healthy-food requirements for school lunch programs. Conservatives in Congress want to make it easier for schools to ignore the healthy-lunch law, liberals — and Michelle Obama — don’t want to see the law gutted, and some school lunch administrators are saying they just don’t have the money to make the law work.

Here’s why I care about school lunches: They are the perfect microcosm for the green case on food. Get them right, and we’d have a model for success in hand (along with a big part of the solution).

The evidence leads me, over and over again, to the following series of conclusions: the overwhelming imperative for cheaper food has made people, rural economies, and the environment sick. The most obvious remedy is to pay farmers a fair price to produce healthier food in a sustainable manner. But higher prices are unfair to people who are struggling to feed themselves, so any good-food fix also has to provide support for the poor.

That’s the genius of school-lunch reform: Because schools have a mandate to feed low-income students, reformers must work holistically, considering economics alongside nutrition.

The current debate is, in fact, more about economics than nutrition. I haven’t seen anyone claiming that the reforms underway via the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act should be watered down to improve health. Instead, the argument is that the law is too expensive for schools.

The School Nutrition Association, which represents school nutrition workers and gets food-industry funding, has argued that schools need more flexibility to avoid breaking the bank. On the other side, Jessica Almy at the Center for Science in the Public Interest said in an email, “What is being billed as bringing ‘flexibility’ to the school foods programs instead would significantly harm the nutritional quality of foods sold in schools.”

So what’s going on here? Is this a venal attempt by the processed-food industry to keep feeding kids junk? Or are school districts really going broke meeting the standards?

There’s not a lot of good data. The School Nutrition Association says that school nutrition directors are telling them that there’s less money coming in under the law. The USDA numbers suggest that school-lunch revenues are actually up. The SNA says that kids are throwing out the healthier foods and have a study linking the reforms to a doubling of food waste. The USDA points to another study that suggests the reforms have decreased food waste. The SNA says that the number of students buying school lunches is down. The USDA seems to concede this, but points to examples of success: “Los Angeles Unified — one of the nation’s largest school districts — has seen a 14 percent increase in participation under the new meal standards.”

Katrina Heron, executive director of the Edible Schoolyard Project, has argued that the conflicting information itself tells us something important: The reform is still a mewling newborn — the USDA still hasn’t even begun to implement some parts of the law. It’s hard to gather data on the success of a policy change until it’s fully rolled out.

We do know that the school lunch reforms have done some good. Kids are eating more fruits and vegetables. And 90 percent of schools are meeting the standards, though it’s still an open question as to whether schools can do it in an economically sustainable way.

Which raises the question: If the real contention is that some schools can’t afford to follow the law, why not ask for financial assistance, instead of asking for a waiver? I put this to SNA representative Diane Pratt-Heavner: Why didn’t it campaign for Congress to give schools enough money to buy healthy foods, instead of campaigning to get exemptions from the healthy food rule?

Simple, she answered: “We’ve been told in no uncertain terms that there’s no money available for increasing reimbursements.”

House Republicans have already demonstrated considerable appetite for slashing food assistance, so Pratt-Heavner is probably correct in her evaluation of the realpolitik at work here. At Slate, Dahlia Lithwick and Amy Woolard wrote that Republicans simply think that these kids are unworthy of assistance:

Last winter, Republican Rep. Jack Kingston of Georgia suggested that maybe students should have to sweep the floors before getting free lunches. In March, Paul Ryan announced that the federal government was giving hungry children “a full stomach and an empty soul.” Each time a school throws a lunch out to protect children from poverty, an angel somewhere must lose its wings.

This seems like the essential policy point that we should be debating. Does an empty stomach really provide a fuller soul? Or, more quantifiably, where’s the data showing that it’s good policy to pinch pennies on school lunches? Does it really make sense to save money by feeding kids diabetes fuel?

We should be having an evidence-based debate about the policy prescription, rather than letting ideological positions send us scrambling. True, Republicans are unlikely to yield in the short term, and that could make life tough for school superintendents. But that political picture would change if school superintendents in every district started demanding that their representatives pay for the mandates of the law, after seeing that it wasn’t going to be watered down. If greens really believe we can make the country healthier by providing good food to everyone, we need to fight for those opportunities to extend the bounty.

(In a related issue, many liberals were up in arms over a provision in the House bill that would limit a pilot project for delivery of summer lunches to rural Appalachia only — but that turns out to have been a bit of a sideshow, if not a misunderstanding.)