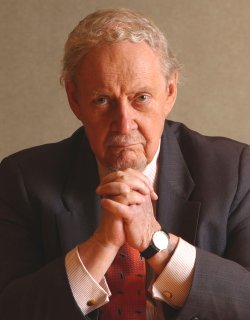

Robert Bork.

Most people, if they think of the recently departed and extremely conservative Judge Robert Bork at all, think of his failed nomination by President Ronald Reagan to the Supreme Court (and maybe his natty facial hair). But Robert Bork deserves credit for more than just inspiring the term “Borked.” He actually deserves credit (or, more accurately, blame) for the domination of our food system by a handful of mammoth corporations. I’m talking about you, Monsanto, Cargill, Tyson, and Walmart.

As we noted last month, farmers feel the brunt of his legacy:

According to a 2007 study [PDF] from the University of Missouri, the four largest companies controlled 82 percent of the beef packing industry, 85 percent of soybean processing, 63 percent of pork packing, and 53 percent of broiler chicken processing. In fact, so much consolidation has taken place throughout the food chain that it can be difficult for any one person to fathom the true effects.

But consumers experience it, too. Walmart now earns one out of every $4 Americans spend on groceries and controls 50 percent of the grocery sales in some cities.

What exactly does Robert Bork have to do with any of this? According to an interview in the Washington Post’s Wonkblog with legal scholar Barak Orbach of the University of Arizona, Bork is considered the father of modern antitrust law, whose influence, Orbach says, he “cannot overstate.” Orbach observes that it was Bork’s legal work in the 1960s that transformed the way the government looked at monopolies and mergers, and led directly to the rise of the mega-corporations that dominate industry after industry.

His main “innovation” was the inclusion of the concept of “consumer welfare” in any evaluation of a potential antitrust violation. In short, he believed that if the consumer benefited from the monopoly, through, say, low prices, then there probably was no antitrust violation. What made this radical was that before Bork, big businesses were considered an inherent threat to small business — the legal term was “inhospitality” — and antitrust regulators wouldn’t consider any potential benefit of consolidation.

As Orbach explains to Wonkblog, Bork saw this assumption that all big business was bad as a one-way ticket to socialism. It was the middle of the Cold War, after all:

He said the Russians were about to take over, through antitrust! In 1963 he wrote an article in Fortune called, “The Crisis in Antitrust,” and he, in that article, he’s describing the socialists who threatened free market forces. It wasn’t too far-fetched if you think about it. If you think antitrust is used to suppress competition, then this is a suppression of the American spirit, of entrepreneurship, of free markets. Who does these things? Socialists.

Sigh.

What Bork did was incorporate the “new” economic theory developed at the University of Chicago (aka “the Chicago School”) — which said the free market was the best means to allocate resources in society, rather than government regulators or Congress — into antitrust law. And if the goal of any analysis of a proposed corporate merger or acquisition was “consumer welfare” instead of protecting small businesses, well, it was a small jump to allowing pretty much every merger and acquisition that came down the pike, since they often led to lower prices and increased “efficiency” in the industries at hand.

He was also influential in convincing judges and the government that “vertical” integration, i.e. the way a company attempts to control its entire production chain, was not inherently anti-competitive. Before Bork, deals and mergers that accomplished this kind of thing were rejected outright by judges. Now, such agreements dominate the landscape — a good example being the harsh and heavily restrictive contracts that poultry processors like Tyson and Purdue are able to foist on chicken farmers.

It was Bork’s legacy that led Obama’s antitrust team to realize there was little they could do to attack current monopolists like Monsanto or beef packers without new laws. (I discussed the pullback of Obama’s antitrust enforcement in the food industry last month.)

Nothing is simple, of course. And Orbach observes that Bork’s work did lead to big benefits to consumers — he mentions telecom, finance, and e-commerce as industries that would be much less consumer-friendly today if not for him. But he doesn’t mention the fact Bork also transformed the American table.

Bork’s work also gave us cheap meat and dairy as well as massive quantities of processed food sold at at heavily discounting supermarkets. Some of this was likely inevitable. But Bork was the one to link economics to antitrust and make consumer welfare the primary goal. Maybe some other jurists would have provided a similar legal framework eventually. But without his extremely conservative approach, the antitrust pendulum might not have swung quite so far. At this point, it will take major legislation by Congress to move it back.

Liberals in the ’80s believed that America had successfully dodged judicial and legal disaster when Senate Democrats kept Bork off the Supreme Court. But it turns out the damage had already been done.