Render isn’t your typical food magazine. It’s not full of glossy photographs of perfectly rustic dinner parties, complete with mismatched china, foraged natural table settings, vintage Pendleton, and perfectly coiffed men who definitely use beard oil. You won’t find dieting tips for swimsuit season among its pages or claims that a $40 Chemex is the only way to brew a decent cup of coffee, either.

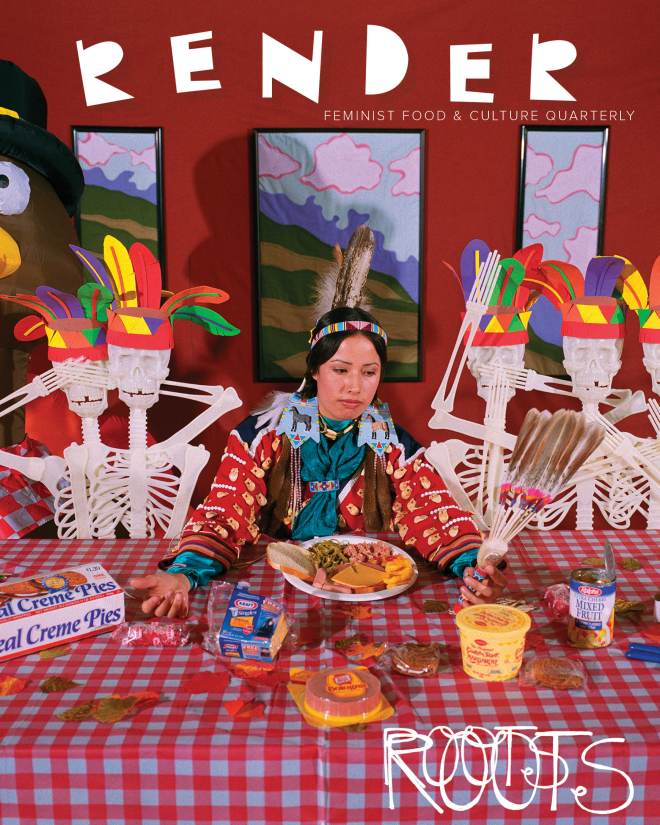

Instead, this food and culture quarterly based out of Portland hopes to totally disrupt the prevailing stereotypes of women in food culture. It also wants you to think long and hard about how race, class, privilege, and politics all influence what and how we eat. Between its website and print editions, a Render issue might have stories about women’s historical roles as beer brewers, “A Basic Bitches Guide to Offal,” and why more and more Jewish women are struggling with eating disorders — all told with a feminist slant. Render’s website also runs a host of other rotating columns — like Breaking Bread, which explores “gastrodiplomacy,” i.e. understanding other cultures through cuisine — and the podcast series the Feminist Fork. The mag’s first issue, “Flesh,” was released in September, followed by “Roots” in December of last year.

Lisa Knisely

Most people shy away from talking politics at the dinner table, but Render wants you to do just that — and at the coffee shop, grocery store, and farmers market, while you’re at it. Grist spoke to Gabi de León, Render’s founder, creative director, and art director, and Lisa Knisely, the magazine’s editor-in-chief, to talk feminism, body politics, and female butchery. Here’s an edited and condensed version of our conversation:

Q. Why start a magazine that blends food culture and feminism?

A. Gabi de León: I entered college developing an eating disorder without even knowing it. I had this eating disorder for not quite a year — I had anorexia — and I was very fixated on what kind of food I was putting in my body and how much and that kind of stuff. I recovered after my first semester, but that eating disorder mindset — it’s more a mental disorder — doesn’t ever really go away. So I was fixated on food for my entire time at PNCA [Pacific Northwest College of Art] and at the time I was an illustration major. I was finding ways to express that through my drawing projects and my design projects.

I had also been taking classes at the Portland Meat Collective, and I felt like women weren’t represented enough in the magazines I had been reading. I was really obsessed with food and I was reading a lot of food magazines. And by the time [my] thesis came along, I was like, “There it is, a magazine that involves women in food somehow.”

Q. For those who have never thought about the connection before, how is food a feminist issue?

A. Lisa Knisely: Initially we were talking about being more focused on gender issues in terms of food consumption, food production, and the restaurant industry. And we’re certainly still absolutely interested in those, but more and more I see how there are these larger, what I would call ethical issues, that are tied in to why we choose to eat, what we eat, and in the ways that we choose to do it. A lot of those issues have to do with power and prestige. Where we’re sourcing the food, who’s cooking it for us, who we’re eating it with, how it’s prepared. Those all bring up these relationships with other people we have to negotiate. And that for me is where feminism really comes in.

Q. How do you think Render turns other food magazines on their heads?

A. de León: One of the most important things, of course, is we’re having discussions that aren’t had in Bon Appétit or Kinfolk or Cherry Bombe or Lucky Peach that can be a little touchy. Those conversations are hard to have when you know that people are going to start some sort of raging discussion about it. But also, there’s a visual element that I considered when I was developing Render, which was making a magazine that visually was not like Bon Appétit or Kinfolk in the way that food can be idealized. I felt like that catered to a certain higher class of people that can afford or have access to those sorts of idealized dining experiences. I want to sell something that is really accessible to everyone of every class, from dishwashers to restaurant owners.

Knisely: We try really hard [not to be] a lifestyle magazine. I want to invite readers into a conversation, and explicitly a political and a critical conversation, as well as be enjoyable and be about cooking and food. I’m not trying to sell people things or tell them what things they should be eating or not. I’m just trying to give them more information and perspective to help them negotiate what’s already out there.

Q. Lisa, in your letter from the editor in the Roots issue, you talk about our desires to know what food means to us and our desires to know what food says about where we come from. What does food mean to you?

A. Knisely: A different staff member writes the letter for each issue. I think Roots was a really good one for me to write because I grew up with farmers on both sides of my family, but then my mom and I moved away and lived in a city. Now I live in Portland and I sort of moved around the country, so I think a lot about what would my family on the farm think about this food trend, or this thing that’s happening in the city and would they think it’s just completely ridiculous. The older I get, the more interested I am in the way that [my family] used to eat and how they eat now and how they provide food for other people.

Q. What are some of the primary stereotypes or ways in which women are portrayed in food culture?

A. de León: Women are extremely underrepresented in food culture, and when they are represented, these days the popular one is, here’s a female chef, hey look there’s this female chef, here’s five female chefs in the United States. Women are being portrayed as these rare female chefs who are super badass and are able to make it in the food industry. And while it’s really great that women are finally getting some recognition in the kitchen, they’re kind of being pointed out as the “other.” It separates them, in a way, from the kitchen.

We’ve reached out to certain women chefs to become part of our Feminist Food February events and some of them have been hesitant because they’re like, “I don’t want to become part of this female chef thing, it’s just too blown out of proportion.” Which is really unfortunate, but that’s the way this whole paradigm has worked out.

Q. Have you always considered yourself a feminist foodie?

A. Knisely: No, I haven’t. Who really identifies as a foodie, right? It’s like “hipster.” No one wants to say, “Oh yes I’m a foodie.” I’ve always really loved food, but I don’t think I’ve really gotten into what I would call “food culture” until the last five years. And I think that’s in large part because I didn’t have access to it before that, in terms of social capital or actual money, and it just wasn’t something my peer group was doing. We were going to Taco Bell and eating at Chili’s. We stayed up late smoking cigarettes at Denny’s. That’s just what we did.

I didn’t identify as a feminist at all until after college. I was adamant that I was not a feminist and I took my first women’s studies class and was like, “Oh my god. All this stuff that I haven’t had words to explain, now I suddenly have words to explain them. Oh, I must be a feminist!”

Q. Describe how Flesh and Roots became themes for your first two issues.

A. de León: I started with Flesh for my thesis because I was dealing with my own issues with my own flesh, basically. I was exploring how to nourish my body and I was also exploring butchery, which is like exploring other bodies and consuming them. So I was like, “Well, that has Flesh written all over it.” After that, we thought Roots would be a good one to go to next … as far as how these sort of ethnic foods are being taken from their cultures and being portrayed in a different way in all these American restaurants. That transplanted food idea, stories of food origins.

Q. What can we do to help remedy these types of issues you’re discussing, as either buyers or consumers of food?

A. de León: Get involved with your food, do your research, question everything.

Knisely: That’s part of the goal with the magazine and of Render as a whole: To invite people to be more cognizant and to have more information to allow them to make different choices.

Q. What’s on tap for issue No. 3?

A. de León: Our next issue is called Timing and it’s coming out in March. We have one piece that we’re going to run about being a mother and working in the kitchen. We have a piece on mentorship, the chefs of tomorrow, so to speak, learning from their mentors and taking their growth as a chef into their own hands rather than following tradition; [and] working in the service industry and having a family. Pieces about eggs, because timing with eggs is everything. Oh! And how palettes change over time. There’s a cool one.