I’m grateful for the responses from Tom Philpott and Ramez Naam to my final post — they round out this series considerably.

I’ll confess to some sensationalism in claiming in the title of my last piece on the GMO controversy that “none of it matters.” Of course it does matter to some degree, and it matters very much to those who have dedicated their lives to the issue. It would have been more punctilious (and less fun) to instead title the piece: “The ferocity of the GMO debate makes it seem much more important than it really is.”

It’s not that we should all resign ourselves to apathy. I’m simply suggesting that — whether your primary concern is the environment, or health, or poverty, or feeding the world — heavy expenditure of political capital on GMOs isn’t going to move you all that far toward your goal.

Both Ramez Naam and Tom Philpott take me to task for underplaying the importance of GMOs, and I actually agree with almost all of what they’ve written here. I agree with Naam that we should be pursuing moonshot technologies like C4 and self-fertilization. But we shouldn’t be counting on those big breakthroughs to solve our problems: They may not ever come. I agree with Philpott that GMO crops have been overhyped and that discussion should stick to the facts on the ground.

That said, each brought up a point that I think deserves a caveat. And, beyond the facts, there’s the larger philosophical question of what to make of all this.

Bt in India

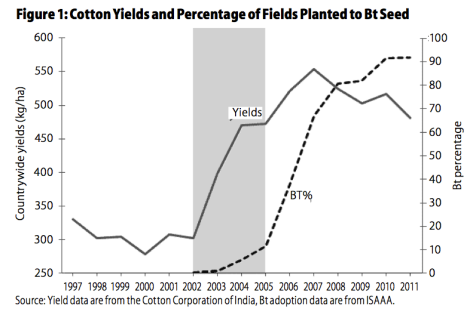

Naam points to the finding that Bt cotton in India is responsible for a big part of that country’s increased cotton harvest. The sociologist Glen Davis Stone countered that finding by pointing out that the spike in cotton production also coincided with new pesticides, increasing fertilizer use, and improved irrigation. Stone also notes that during the early part of that cotton boom, hardly any farmers were actually buying official Bt seeds.

From Constructing Facts: Bt Cotton Narratives in India, Economic and Political Weekly

But there’s one more layer of nuance here: A counter-critique points out that there was an awful lot of illegal planting of unofficial Bt seeds in those early years — maybe illicit GMOs account for the big jump in productivity. As always, it’s hard to nail down the facts in this debate. Edit: Also a counter-counter-critique.

Pests evolve resistance

It’s absolutely true that weeds and insects evolve in ways that make GMO traits less effective — I’ve looked at herbicide tolerance, and I agree with Philpott on the generalities. Herbicide-tolerant GMOs deserve some credit for getting farmers to switch to glyphosate, which is much less toxic than other herbicides, and also for allowing some more conservation tillage, which has major environmental benefits. But as weeds develop resistance we’re ramping up increasingly toxic sprays. That’s not a good endgame.

The Bt crops are more complicated. Philpott points out that western corn rootworms in the Midwest have become resistant to Bt, and this has led farmers to apply more insecticide. But even these increases haven’t brought insecticide application back to the levels of the bad old days before Bt GMOs. And there’s reason to believe that the effectiveness of Bt isn’t going to vanish anytime soon. When I first learned about the evolution of resistance, I assumed that once a species had figured out how to thwart a pesticide, the genie was out of the bottle, and the pesticide automatically became useless. But that’s not the case.

Back in 1994, before the introduction of any GMO crops, the entomologist Bruce Tabashnik set out to determine what kind of insect resistance would evolve if we engineered Bt into plants. At the time, some people were saying that Bt was different, and that insects wouldn’t be able to evolve resistance. But Tabashnik found that some insects were already resistant, pre-GMO, because Bt was sprayed as a pesticide, mostly on organic farms. If farmers were prudent about the way they used Bt, Tabashnik said, that resistance wouldn’t dominate the gene pool. That’s proven to be true. In the Midwest, where farmers have planted Bt corn year after year, Bt resistance is rampant — but not in Arizona, where Tabashnik now works.

We shouldn’t write Bt off, but we also shouldn’t give agribusiness a free pass on this one. I place most of the blame for profligate use of Bt on the seed companies and on government: Those with the power to regulate the way that farmers plant should set incentives that prod them to do the right thing.

The relationship between sustainability and GMOs

I’ve heard from a lot of people, not just Philpott, that I should oppose GMOs because what we really need is low-input, agro-ecological farming. I haven’t been surprised by that, because that was my position before I started this research. I still think that agro-ecological approaches are necessary, but I no longer think that all GMOs necessarily move us away from that goal.

When I came into this project, I saw conventional modern agriculture and low-input, agro-ecological approaches as two utterly separated paths. Any technology that advanced mainstream farming was bad because it took us further away from truly sustainable agriculture. Even if GM made things a little better, I was inclined to discount it, because it just made the bad system more attractive. My mind has changed by talking to farmers, like these.

After that reporting I replaced that image of two diverging roads with an image of a tangled wood: Farmers who care about sustainability — whether they are organic or mainstream, big or small — are struggling through the thickets toward that goal. The most inspiring farmers to me are not the ideological purists calling for revolution, but the pragmatists using whatever tools they can to make their way a little closer to sustainability. Philpott actually played a key role in changing my mind, by penning this fine article about Ohio farmer David Brandt.

Brandt is a conventional American farmer who has figured out how to build up his topsoil, radically reduce erosion, and slash his fertilizer and pesticide use, all while maintaining yields. He hasn’t done this by backtracking to that metaphorical crossroads, and then taking some high road to sustainability. Instead, he’s cut straight through the forest from the place he started. He still uses some herbicides and plants GM seeds, though he says he would happily dispense with them. But GMOs are hardly leading Brandt down the path to pollution and disaster.

The fact is, there is no high road to sustainable ag: We’re just figuring it out as we go along. And we are going to need a lot of different ideas to do it.

Now, Philpott is much more careful than most in making his argument. He doesn’t just say “sustainable farming is good, therefore GMOs are bad”; he provides a mechanism to connect those two things. He argues that the success of GMOs has allowed the big ag conglomerates to consolidate power and to lobby against policies that would allow for more sustainable farming. And this brings me to my final point.

The role of money and power

When any business becomes large and powerful, it will begin using its influence to protect itself and improve its position. Sometimes this is pretty obvious (see all the money that went into defeating the GMO labeling bills), but often it’s pretty subtle. At this point, for instance, we have so much research invested in our agricultural system that alternatives often appear anemic. As small farmers in poor countries work to improve their lot, they often do the obvious and imitate the rich Americans. In some cases, this is a victory of momentum over science. There may be much better ways for these small farmers to improve, but to find those practices we need more research focused on them, which may not provide a profitable return on investment.

So, when Ramez Naam suggests that we should be using GMOs to help feed the world and improve the environment, I want to add a note of caution: There’s an entire industry pushing the argument that GMOs are the solution. I agree with the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development that GMOs could be part of the solution, but we shouldn’t let the hype distract us from all the other ideas out there.

At the same time, I’m uncomfortable with opposing GMOs simply as a means to restrain the power of the seed companies. To use an analogy here: I really dislike our car-dependent transportation system — the emissions, the death toll, the road rage (and that’s just my average trip to the store) — but I would have a really hard time justifying opposition to all internal combustion engines. Sure, opposing engines would be a lever to counterbalance the power of automakers, petroleum companies, and the road-building lobby. But I’d be much more comfortable in opposing the most polluting SUVs, while supporting tougher gas-mileage regulations.

There are lots of problems associated with GMOs. I just want to focus directly on fixing those problems, rather than turning GMOs into a vague representative boogieman. I see problems with seed patents, problems with overuse of pesticides, problems with the lack of funding for research on agricultural alternatives. I care deeply about these things. But I’m worried that the discussion has become so ossified over GMOs that it’s not helping those causes. We’ve focused so tightly on GMOs that people tend to lose sight of those bigger things.

One last thing

The first third of Jon Mooallem’s brilliant book Wild Ones is about polar bears. Just as GMOs have become a symbol for all our agricultural anxieties, polar bears have become a symbol for climate change — but, Mooallem writes, that metaphor has begun to fray:

The polar bear had been useful as a pure white, cuddly harbinger of horrible things — a victim of climate change just at the right remove from our own species to be palatable and approachable and inspire us to change. Until now, working to save polar bears and working to stop climate change had meant the same thing. But they are starting to diverge… If we choose to help them survive it will require the kind of narrow, hands-on management — like getting out there and feeding them meat — that does nothing to stall climate change. Meanwhile, conservationists will have to work hard and more inventively to spin the animals’ worsening predicament in the same inspiring terms, without seeming dishonest or oblivious.

If you burn fossil fuels to airlift bears out of danger, you’re prioritizing the bear ahead of the climate. In this way, advocacy on behalf of the symbol — the polar bear — works against the larger issue of climate change. In the same way, the symbol of GMOs has eclipsed the causes it symbolizes. Our urgent needs are to alleviate poverty, improve the environment, and face the fact that many of us no longer trust the people who bring us our food. Right now, our political capital is misspent if we’re only addressing GMOs narrowly without touching those larger issues.