This post is part of Protein Angst, a series on the environmental and nutritional complexities of high-protein foods. Our goal is to publish a range of perspectives on these very heated topics. Add your feedback and story suggestions here.

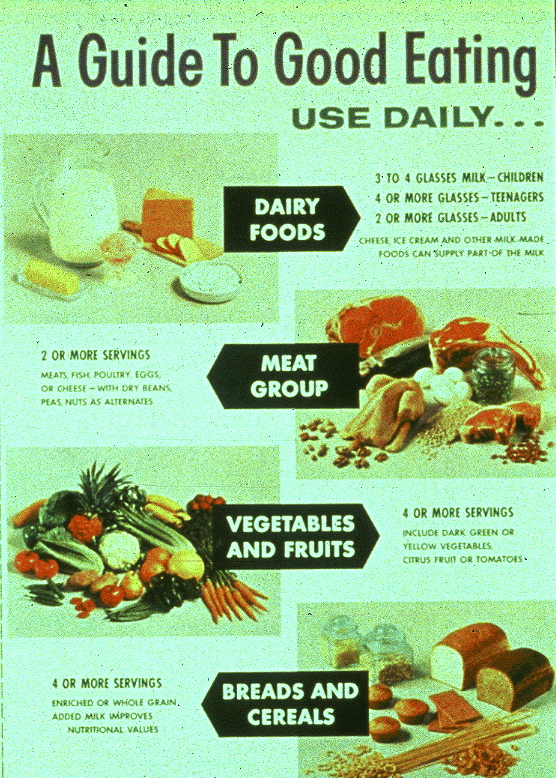

Early USDA guidelines highlighted the "meat group."

Most vegetarians are tired of being asked, “Where do you get your protein?” by a seemingly concerned family member, friend, or even stranger.

I know many vegetarians and none of us have come close to suffering from Kwashiorkor. Never heard of it? It’s a form of malnutrition from lack of protein, found in areas of famine and extreme poverty. Protein deficiency is rare in the developed world, despite a significant portion of the population eschewing meat.

So where did this idea come from that vegetarians and vegans are doomed to a life of protein deficiency?

Protein propaganda

We have the meat industry to thank for the message that animal products equal protein. Decades of science tells us that a mostly plant-based diet is optimum for health (and prevention of obesity, especially in children), and that eating too much meat, cheese, and other animal foods contributes to heart disease, cancer (especially colon cancer), and other chronic illness such as Type 2 diabetes.

Such science is very inconvenient for the industries that promote these foods. So they’ve had to get creative. One way to distract attention away from heart attacks and colon cancer is to conflate the idea of meat with a nutrient that we do in fact need: protein.

And all signs indicate that this spin has worked. If you ask Americans why they eat meat, one of the top answers (if not the No. 1 answer) would likely be, for the protein. This, combined with effective marketing to promote the idea that meat tastes really good, is manly, and so forth (not to mention federal subsidies and industry consolidation to help ensure meat remains cheap), has been a huge success.

And how about that ubiquitous Beef: It’s What’s for Dinner ad campaign? Most Americans have no clue that behind these generic food messages is the federally organized Beef Check-Off program. While funding to pay for the marketing comes from industry, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) administers this program (and numerous others like it). (In 2010, the beef industry was accused of misusing the money for lobbying. In a related blog post, nutrition professor Marion Nestle said these funds “reek of conflict of interest.”)

The 1991 food pyramid included the meat, poultry, fish, dried beans, eggs, and nuts in one group and received a great deal of industry push back

Protein politics at USDA

Long before MyPlate, MyPramid, and other dietary guidance icons, the federal government took a simpler approach — the four food groups: The meat group (beans and nuts were also listed but as “alternates”), the milk group, the bread/cereal group, and the vegetable/fruit group. For years, this served the meat industry’s interests quite well.

That is, until the science showing that meat-centered diets were causing disease became too compelling for the federal government to ignore. In 1979, the feds released a report advising Americans to eat less red meat. The meat industry was not pleased, to put it mildly. As a result of the backlash, this report, explains Nestle (in her must-have-on-your-shelf book Food Politics) was “the last federal publication to explicitly advise, ‘eat less meat.'” From then on, the feds adopted the industry-friendly but confusing “choose lean meats” euphemism. This is essentially where things stand today.

In 1991, the meat industry threw such a fit over the soon-to-be-released Food Guide Pyramid (which gave meat and dairy less prominence) that USDA delayed the release for a year and spent $1 million on consumer surveys.

While the most recent MyPlate icon, which recommends filling half your plate with fruits and vegetables, is a huge improvement, it’s still inadequate and confusing. For example, it still states that protein is a category of food. As Nestle explains:

Protein is not a food. It is a nutrient. USDA must think everyone knows that “protein” means beans, poultry and fish, as well as meat. But grains and dairy, each with its own sector, are also important protein sources. The meat industry wants you to equate protein with meat. It should be happy with this guide.

Reframing the discussion

Even the sustainable agriculture movement too often perpetuates the protein-equals-meat myth. As I wrote earlier, no shortage of resources exist to guide those who are inclined to keep eating meat to do so in a kinder, gentler manner, at least when it comes to the environment and animal treatment.

However, with a few notable exceptions (including the growing Meatless Mondays campaign and New York Times columnist Mark Bittman, aka the “less-meatarian”), most good food leaders (other than vegetarian groups, obviously) are not talking about eating less meat or promoting other, healthier forms of protein. And I don’t buy into the idea that grass-fed beef and pasture-raised pork are healthier. These expensive alternatives still don’t compare to nutrient- and fiber-rich plant-based protein sources.

The best way to counter protein propaganda is for the good food movement to come together on this relatively simple message: Eat less meat. I guarantee the meat lobby will hate us for it. But I can live with that.