When Nick Papadopoulos looked at all the veggies that didn’t sell at the farmers market, he felt terrible. Papadopoulos is general manager of Bloomfield Organics, and he’d seen all the sweat, all the nutrients, all the coaxing and coddling that it had taken to persuade the land to produce this bounty. These were beautiful, well-proportioned, organic vegetables! And now they were bound for the compost heap. He sipped his beer and thought, there has to be a better way.

We end up throwing out a lot of the food we grow. According to an analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council, we’re tossing 40 percent of our food, the equivalent of $165 billion wasted — giant lakes of water, mountains of fertilizer, and megajoules of energy, all squandered.

If we’re interested in scaling up regional food systems, we’re going to need a lot more reasonably priced, locally grown calories. And one obvious place to go looking for those calories is among those foods valued so low that they rot, rather than selling in a nearby city. The question is, how do you get people to eat those unloved, unwanted veggies? In other words, how do you solve Papadopoulos’ problem?

Papadopoulos told this story recently at a meeting of the Commonwealth Club, convened by the Center for Urban Education about Sustainable Agriculture, to discuss the problem of food waste. Attendees noshed on appetizers made from carrot tops and beet stems in miso and ginger. The NRDC’s Dana Gunders, whose report triggered a great deal of interest on the issue, told the audience about a peach grower she’d talked to whose experience was similar to Papadopoulos’. He was leaving thousands of pounds of peaches to rot on the ground even though, as he told Gunders, “I wouldn’t be able to tell what was wrong with eight out of 10 of them.”

It’s a confounding problem, because it shouldn’t exist at all: There’s food available, and there are people out there who want the food. We just haven’t figured out how to connect the dots between supply and demand.

But sometimes people like Papadopoulos do figure it out. On that particular day, Papadopoulos simply pulled out his cellphone and posted a plea on Facebook. There was a wave of response, and soon the vegetables had been claimed. Papadopoulos went on to build a web-based service called CropMobster to handle these kinds of transactions. Maybe the key to reducing food waste is simply creating a more efficient marketplace.

Well, a marketplace is the first step, but even after you’ve made an internet connection and completed an electronic transaction, you still need to find a way, down in the real world, to move the food from seller to buyer. “There’s no system to recover and redistribute edible food,” Dana Frasz said. But her organization, Food Shift, is tackling that problem, helping companies and governments cut down on food waste and showing how to get unused calories into a loving home (or a belly).

The third step is education: People simply don’t know how to assess the quality of their food, so they instead look for aesthetic perfection. Gunders is working on a book to address that problem, teaching people how to hear the voices of vegetables and interpret the language of legumes: If mushrooms have black spots, do you need to throw them out? How much credence should to you give to the “best-by” date? If people understood these things, they’d be much less likely to throw out good food in their own kitchens.

No one knows for certain how much of the problem belongs to individual eaters, and how much with farmers, grocers, and restaurateurs. But we do know that household food waste has a much bigger impact, because it’s taken so much energy to move that food to the eater and prepare it.

Teaching people to eat the food they would otherwise waste doesn’t mean teaching them to lower their standards, said Staffan Terje, the chef and owner of the San Francisco restaurant Perbacco. It simply means teaching people to try new things.

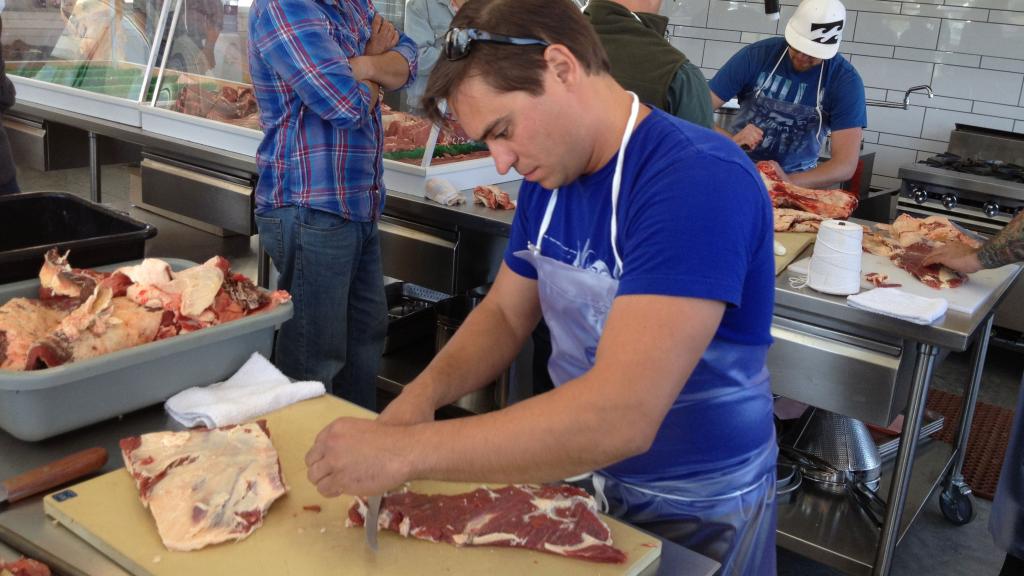

Terje is fanatical about eliminating food waste in his own kitchen. But he can’t do it by compromising quality or else, as he said, “you won’t come to my restaurant.” So he looks for alternative solutions.

At the farmers market, for instance, people tend to avoid the apricots that have been out in the heat too long, and have begun to develop little brown spots. Terje will tell the farmer, “Look let’s make a deal. Do you really want to burn more fuel trucking that back to the farm?” He’ll buy the apricots at a discount and turn them into a preserve or chutney, where looks don’t count. As a bonus, these overripe fruit have higher sugar content, making them ideal for this use.

These three solutions — connecting sellers and buyers, moving the food from the former to the latter, and teaching people to see their food more clearly — could go a long way toward reducing food waste. The United Kingdom was able to drive down household food waste by 19 percent using these kinds of techniques.

But there’s also a more direct way of solving the problem: Make food more expensive. The ultimate reason we throw food away is that we don’t value it very much. It’s more efficient to leave peaches to rot in the field than to go to the trouble of finding a buyer.

Papadopoulos jokingly suggested that the government should mandate dumpster diving around the country — but if food costs were more significant, people would be lining up to grab food before it ever got to the dumpster. The average American wastes 10 times more food than the average southeast Asian, because food is a much smaller part of an American’s budget. It’s time to put the emphasis on the production of quality food, rather than the production of cheap food.

As Gunders pointed out, Americans would hugely exacerbate our obesity problem if we actually ate everything we wasted: “There’s only two things that can happen to all these extra calories,” she said. “Either we’re eating them, or we’re not. Either is bad.”

The ideal solution would be to produce fewer calories per person and pay a little more for it — enough so eaters will actually value the food they buy, and enough to support strong farming communities. If we start paying farmers a truly fair price for environmentally responsible, high-quality food, we’ll have tons of entrepreneurs working overtime on those other three solutions, and cashing in on waste.