What can old bones teach us about adapting to climate change? More than you’d think.

In a new paper published in the journal PNAS last week, 25 archaeologists and anthropologists analyzed thousands of years’ worth of human remains from nearly every continent to learn how ancient people responded to rapid shifts in the climate. They studied the health of the people during hard times, comparing characteristics between societies to see what made a difference.

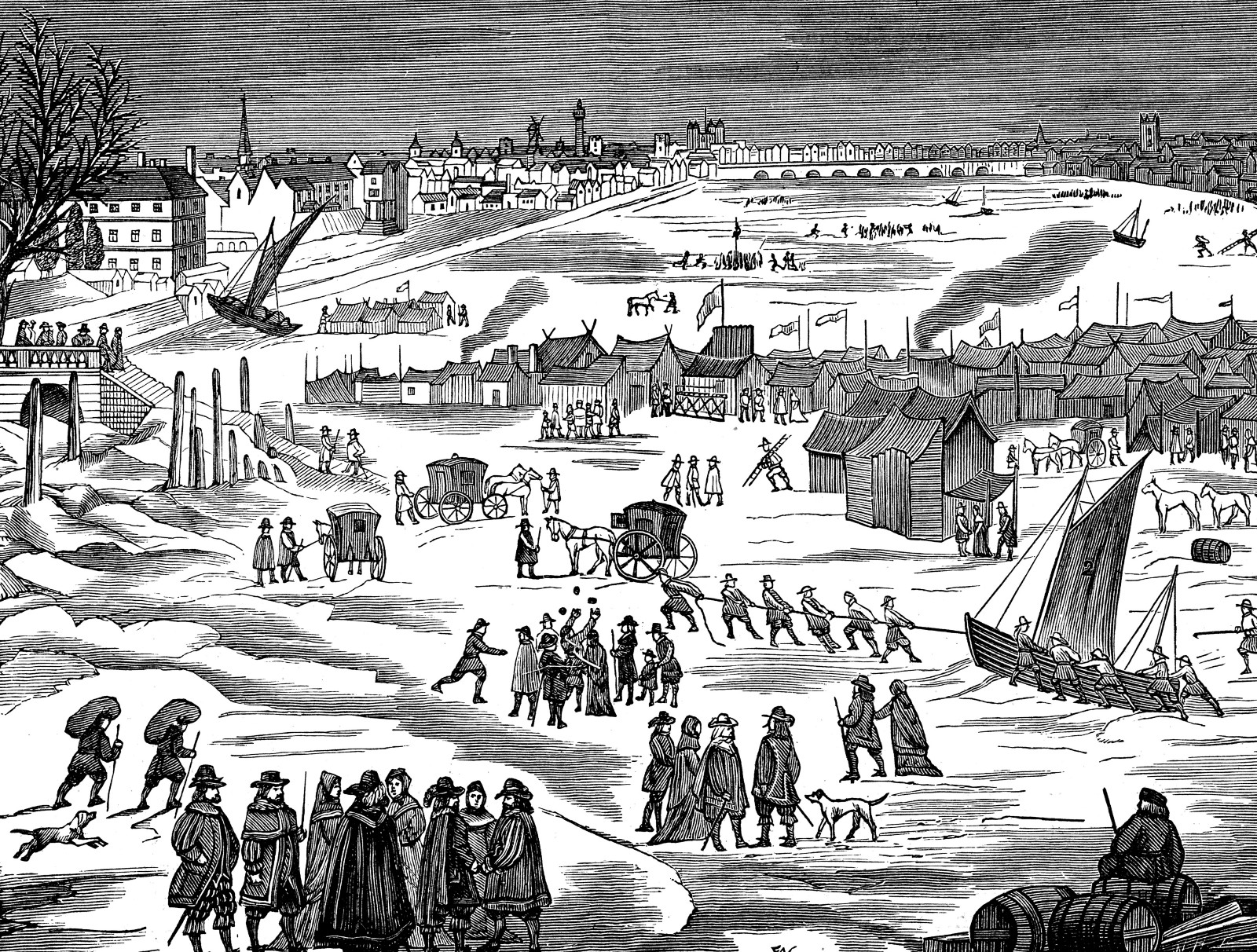

Wherever they looked, they found that some cultures adapted to drought, changing rainfall patterns, and fluctuating temperatures better than others. In general, when people lived in rigid, hierarchical societies, depended too much on agriculture, and lived in close quarters, they faced the most destruction from these challenges. In Europe, for instance, the Little Ice Age coincided with the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War. On the other hand, people who lived in more mobile societies with diverse food sources and more flexible social structures fared better, cooperating with each other to survive.

Contrary to the story that often gets told, migration, violence, and civilizational collapse are not inevitable responses to environmental stress, said Gwen Robbins Schug, the lead author of the paper and a professor of biology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. While relocation is often a solution for coping with shifts in the climate, it’s not the only way, and doesn’t necessarily lead to conflict and violence. “There are many times in history where people successfully navigated climate and environmental change and they didn’t migrate,” Robbins Schug said.

Recent research has countered the idea that abrupt shifts in the climate unavoidably led to the breakdown of ancient civilizations. Sure, environmental shifts caused serious problems — and sometimes catastrophe — but pop-science books have tended to focus on the most dramatic tales, such as the collapse of Easter Island or the Mayan civilization, sometimes fudging the facts to fit a particular narrative. They also tend to ignore how many groups managed to survive, responding and reorganizing without losing their core identity. This preoccupation with crumbling societies has resulted in a warped picture of the past, one report published in Nature argued.

It has also fueled a fatalistic view, sometimes called “doomism,” about our ability to survive the alarming rise in temperatures today. Misconceptions about collapse, migration, and violence in the face of climate change could end up shaping modern-day policy decisions, with serious consequences, Robbins Schug argues. “What should actually be driving policy is the notion that cooperation is much more common in human evolution,” she said. “We would not be where we are today without cooperation.”

Robbins Schug and the other researchers assessed dozens of studies looking at societies stretching back 5,000 years through the Middle Ages, pulling out common themes in how they responded to environmental stress. They studied societies hailing from locations in present-day North America, Argentina, Chile, China, Ecuador, England, India, Japan, Niger, Oman, Pakistan, Peru, Thailand, and Vietnam.

What they found was a divide between large, rigid societies and smaller ones that were more nimble and cooperative. Consider the megadrought that hit Asia around 2200 B.C., one of the most severe climate events in the last 10,000 years. Prior to the drought, the Indus Valley civilization in contemporary Pakistan and northwest India had grown rapidly, building dense, complex cities and trade routes. But diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis thrived in tight quarters and spread through trade, economic opportunities started drying up, and unpredictable monsoon rainfall made the situation worse. Violence spread; Indus cities were largely abandoned within 200 years.

By comparison, the drought didn’t do as much damage to hunting-and-gathering communities in Japan, China, and the United Arab Emirates, less hierarchical societies with more dietary diversity. In Japan, people in Jomon cultures ate lots of chestnuts that they cultivated in addition to what they hunted, gathered, and fished.

The modern-day Four Corners region in the American Southwest offers another example of how to cope with environmental stresses. From the years 800 to 1350, temperatures swung from one extreme to the other, and the area oscillated between drought and floods. But at Black Mesa in northern Arizona, the desert-farming population grew slowly and steadily thanks to a series of adaptations. People moved around as water sources shifted, created “eco-niches” to attract rabbits to supplement their diet, and built widespread cooperative networks to trade resources across a large area.

The new paper suggests that a preoccupation with climate-driven violence might come, in part, from a focus on European history. The Little Ice Age that started in 1300 was marked by widespread famine, epidemics like the Black Death, and wars. The increase in violence seen during this time wasn’t an inevitable outcome of a changing climate, the study’s authors argue, but an example of how a specific historical and cultural context created “an atmosphere conducive to violence as a response to stress,” with deep economic inequality, endemic warfare, and religious fundamentalism as backdrop.

The study also suggests that migration may be a healthy adaptation to a changing world. While migration is often painted as a scary, unnatural force, some say it might be time to reframe the phenomenon, envisioning it as a way to move out of harm’s way and actively seek better living conditions. For instance, during times of high aridity in sub-Saharan Africa, migration offered “a successful strategy for dwindling local resources,” the study says.

It’s a reminder that, even though the scale of modern-day climate change today is unprecedented and frightening, people have dealt with environmental problems before. You could say that some lessons for how to deal with climate change are written in their bones.