Stacey Branscumb didn’t know anything was wrong with the water in his Benton Harbor, Michigan home until a local faith leader, Reverend Edward Pinkney, alerted him that several families in his neighborhood had found dangerous levels of lead coming out of their taps. After that, Branscumb began to wonder if his home had been affected too — it would explain his pets getting sick and in some cases, dying unexpectedly.

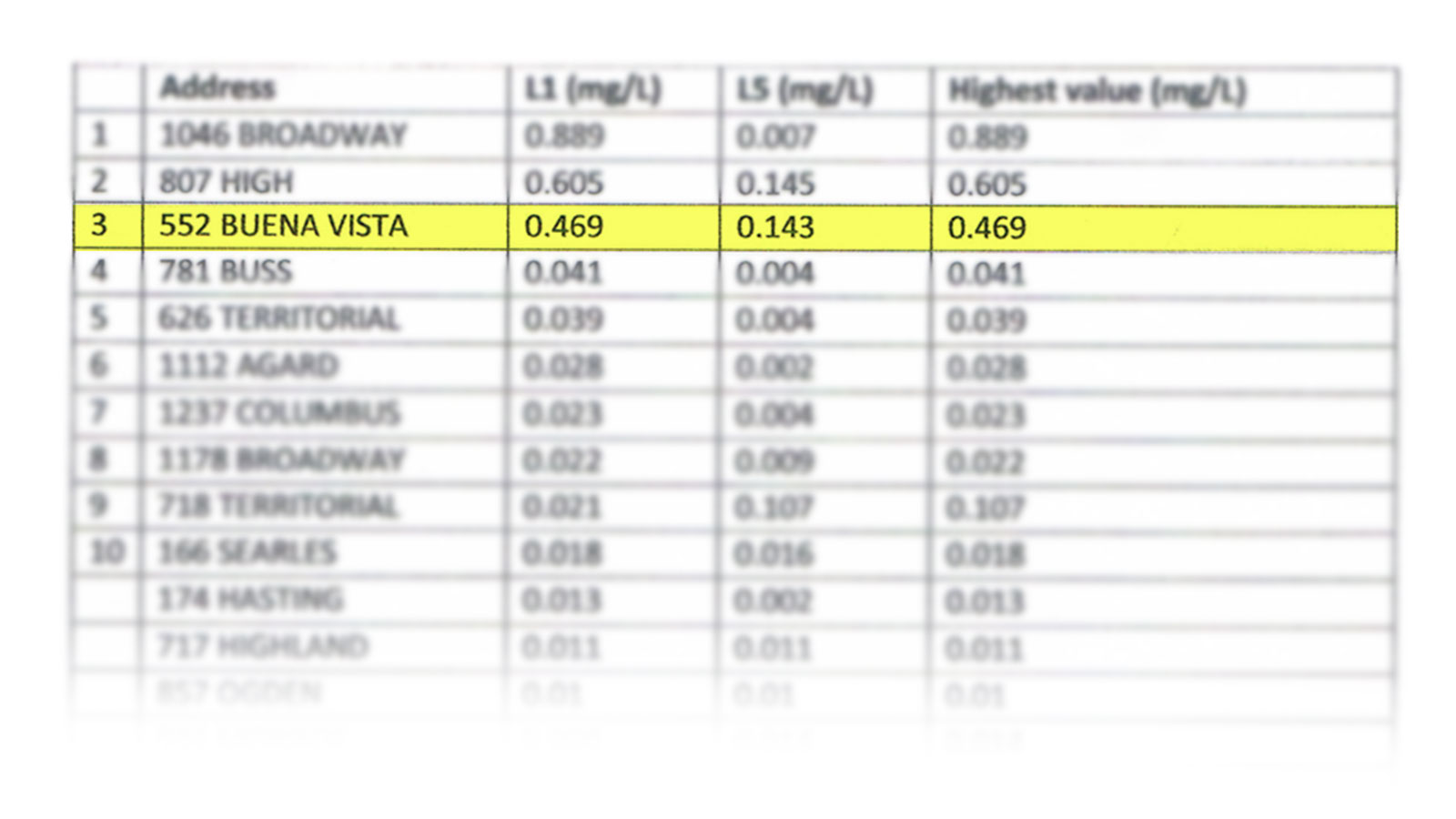

Branscumb got his water tested in 2019 and found high levels of lead. The next year, his water tested high again. Then this June, the tests came back showing a lead concentration of 469 parts per billion (ppb) — almost 32 times higher than the federal limit of 15 ppb.

“Every year he always had high lead levels, but this time it was ridiculous,” Pinkney said. “Just by looking at Stacey’s water, we knew right away that there was a major problem.”

For at least three years, Benton Harbor residents have had high levels of lead in their drinking water. Yet still nothing has been done to fix the problem. The water in Branscumb and his neighbors’ homes remains undrinkable today, with levels of lead rivaling those found in Flint, Michigan, seven years ago.

To force action on the issue, 20 environmental and advocacy groups filed a petition earlier this month to the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, citing an “imminent and substantial endangerment of public health.” Lead exposure for kids can result in long-term health effects, from brain and nervous system damage to learning and behavioral problems. In adults, it can cause high blood pressure, joint and abdominal pain, and miscarriage.

The petition calls on the federal government to provide clean water for Benton Harbor’s 10,000 residents and for the removal of 6,000 lead pipes. Signatories of the petition — which range from local groups like the Benton Harbor Community Water Council to national organizations like the Natural Resources Defense Council — say the situation has become a clear environmental and racial justice issue: The EPA took swift action this summer to fix lead contamination in the drinking water of a majority white city in West Virginia. But it hasn’t acted yet for Benton Harbor, where 90 percent of residents are people of color, and 45 percent live below the federal poverty line.

“It’s a simple matter of law and justice that the people of Benton Harbor deserve safe water, regardless of their race or income,” Nick Leonard, executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center and one of the petition’s organizers, said in a press release. “It is time for the federal government to step in to protect this low-income community of color from toxic water.”

Benton Harbor is not alone in being left behind. As lead pipes age across the country, communities of color are most often the ones being stuck drinking contaminated water. An analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council, or NRDC, last year found that communities of color and low-income neighborhoods are more likely to be in violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act, and in violation for longer periods of time. In Michigan, Highland Park, Harper Woods, and Eastpointe are all majority communities of color that have also struggled in the last two years with high lead levels. Nationally, cities like Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Chicago, Illinois are being affected.

In July, after sampling in Clarksburg, West Virginia showed high levels of lead in drinking water, the EPA issued an Emergency Administrative Order. The order required the city to identify homes and businesses with lead service lines and provide alternatives for clean drinking water. Clarksburg is the inverse of Benton Harbor — 92 percent of its residents are white. “The situation in Benton Harbor is at least as extreme, and could be more extreme, than the case of Clarksburg, West Virginia,” the new petition argues.

When asked about its action in Clarksburg and inaction in Benton Harbor, Tim Carroll, a spokesperson for the federal EPA told Grist, “[The] EPA has received the petition and is carefully considering the issues and concerns raised by this community. We are closely monitoring lead-related health issues in Benton Harbor.”

The elevated levels of lead in Benton Harbor’s drinking water are being caused by the corrosion of old pipes — a natural process as this infrastructure ages. Residents point out that while nothing has been done to fix Benton Harbor’s lead problem, its mostly white neighboring city, St. Joseph, which also had lead pipes, doesn’t have any issues with lead in its water. St. Joseph’s water plant superintendent says the disparity could be for several reasons, including the chemicals used to treat the water and total water use. Others, like Pickney, say it’s because of St. Joseph’s resources to resolve the issue. The city of St. Joseph has a poverty rate of just 7 percent, compared to more than 45 percent in Benton Harbor.

Cyndi Roper, a senior policy advocate for the NRDC and one of the petition’s signatories, told Grist the groups filed the petition because, “we were increasingly concerned about the lack of urgency with the staff at EGLE.”

EGLE, or the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, is the state agency responsible for regulating issues like water contamination in Michigan. The agency was made aware of the elevated lead levels in water in 2018, during routine water testing. Following that, they advised residents to let their water run first before using it, and to use a lead reducing water filter provided by the county health department. The city also installed corrosion control technology at its water plant in March 2019 and began the process of replacing some of its lead lines.

“The conversation was focused on treatment techniques and how they were going to control corrosion in the water,” Roper said. “That is absolutely important, but we have to be sure that residents aren’t drinking high levels of lead while they experiment with their corrosion control.”

In the absence of state-provided clean drinking water, Pinkney and other activists hosted a water giveaway in September, distributing 500 gallons of water to residents.

The Lead and Copper Rule, part of the Safe Drinking Water Act, is a federal regulation that limits the concentration of these metals in drinking water. Michigan has the strongest state-level version of the Lead and Copper Rule in the country, after revisions were made in 2018 following the Flint water crisis: It bans partial lead distribution lines, requires water utilities to pay for the entire length of the pipe being replaced, and uses a more accurate method of testing the water.

“If Michigan’s stronger-than-other-states’ Lead and Copper rule still allowed this to happen, then we have serious problems with the way that we are approaching lead and drinking water,” Roper told Grist.

The federal government is partly to blame as well.

The federal rule only requires cities to test drinking supplies every three years, and only 10 percent of homes need to be tested. Cities aren’t required to notify the public of a lead issue until levels reach the federal limit of 15 ppb, although public health experts stress there is no safe amount of lead in water. And it’s all based on city wide data, so if at least 90 percent of homes test within the limit, a water utility is in compliance. If harmful levels of lead are found, it can trigger a required replacement of lead service lines, but the federal rule allows 33 years for that replacement to happen.

The EPA is currently deciding whether or not to reissue the Lead and Copper Rule, or make revisions to it. Over the summer the federal agency held roundtables across the country to get feedback from communities. Benton Harbor was one of the cities that participated.

Among several changes to the federal Lead and Copper Rule, Roper is advocating for a 10-year limit on replacing infrastructure, and to reduce the action incompliance level of lead in water from 15 ppb to 5 ppb. The EPA is expecting to announce next steps before mid-December.

Earlier in September, Michigan’s Governor, Gretchen Whitmer, proposed spending federal pandemic relief money on replacing lead lines — $20 million of which would go to Benton Harbor to replace all lines within 5 years. The proposal would still need to be passed by the state’s legislature. “That’s a process,” Pinkney said. “We can’t wait six months for [Governor Whitmer] to do something. We can’t even wait another day. We have to start thinking about our children and their future and clean this water up — and do it now.”

At the federal level, the U.S. Senate passed a bipartisan infrastructure bill this month that would provide $15 billion for lead service line replacement across the country. Estimates show the price tag on the project, however, is between $28 and $47 billion. According to a survey conducted by the NRDC, there are up to 12 million lead service lines across the country that are, or might be, lead and will need to be replaced in the coming years.

“Until we get all of these lead pipes out of the ground all the way from the curb to the inside of the home, we’re going to continue having extensive problems with lead in drinking water,” said Roper. “Each community that has these lead pipes is only one mistake away from potentially having their own water crisis.”