This week, the United States government and leading climate researchers from institutions across the country released the Fifth National Climate Assessment, a report that takes stock of the ways in which climate change affects quality of life in the U.S. The assessment breaks down these impacts geographically — into 10 distinct regions encompassing all of the country’s states, territories, and tribal lands — and forecasts how global warming will influence these regions in the future.

Unlike other climate change-focused reports that are released annually, the National Climate Assessment comes out once every four years. The length of time between reports, and the volume of research each report contains, allow its authors to make concrete observations about climate-driven trends unfolding from coast to coast and island to island.

In the previous installment of the report, released in 2018, the government warned that rising temperatures, extreme weather events, drought, and flooding threatened to unleash a surge of fungal pathogens, toxic algal blooms, mosquito- and tick-borne illnesses, and other climate-linked diseases. The new report, published on Tuesday, demonstrates that this prediction is unfolding right on schedule.

“Health risks from a changing climate,” the report says, include “increases in the geographic range of some infectious diseases.” West Nile virus, dengue fever, Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, rabies, and Valley fever, carried by mosquitoes, ticks, mammals, and soil, are among the infectious diseases the report has identified as “climate sensitive.” Climate change isn’t the only reason more people are being affected by these illnesses — urban sprawl, deforestation, cyclical environmental changes, and other influences are also at play — but it’s a clear contributing factor.

Here are a few of the diseases that the Fifth National Climate Assessment warns are spreading into new parts of the country as a changing climate sends their carriers creeping into different areas.

Ticks

In the U.S., the vast, vast majority of reported cases of vector-borne disease — defined as diseases spread by blood-sucking invertebrates such as ticks, mosquitoes, and fleas — can be traced to ticks. Lyme disease, which has long been prevalent in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic, is becoming endemic to the Midwest as winters in that region become milder. Western black-legged ticks, which can carry Lyme, are even creeping into Alaska, where conditions have historically been too harsh for the eight-legged bloodsuckers to survive. The costs of treating Lyme, which can cause effects that range from flu-like symptoms to neurological disorders, are “substantial,” the report says. One analysis puts the annual cost of treating Lyme, which affects some half a million Americans each year, at $970 million.

Lyme isn’t the only tick-borne illness expanding in range and severity across the U.S. The Gulf Coast tick, which carries multiple diseases, has been expanding through the Southeast. Deadly illnesses such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever, babesiosis, and alpha-gal syndrome, all spread by different kinds of ticks, could reach new areas as temperatures continue to rise, the report says.

Mosquitoes

Much like ticks, mosquitoes are benefiting from milder winters and longer breeding seasons. The uptick in flooding across major swaths of the country, brought on by a warmer, wetter atmosphere, can also be a boon to the winged insects. Every part of the contiguous U.S. is seeing changes in the geographic range and prevalence of mosquito-borne illnesses.

West Nile virus, a disease carried by Culex mosquitoes, is expanding in the Northeast and becoming a bigger threat in other parts of the country, like the Southeast, as the planet warms. “Black and under-resourced neighborhoods in Chatham County, Georgia, were identified as hotspots for West Nile virus,” the report says. The majority of people who contract West Nile experience no symptoms, but people who are immunocompromised, elderly, or pregnant, or who have comorbidities, often have severe symptoms and can even die.

Dengue fever, a deadly viral infection, is becoming a bigger risk in the contiguous U.S., Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Hawaiʻi, and the U.S.-affiliated Pacific Islands. Malaria, a parasitic mosquito-borne illness that was eradicated from the U.S. in the 1950s, is now a burgeoning threat in the Southeast and Pacific Islands regions.

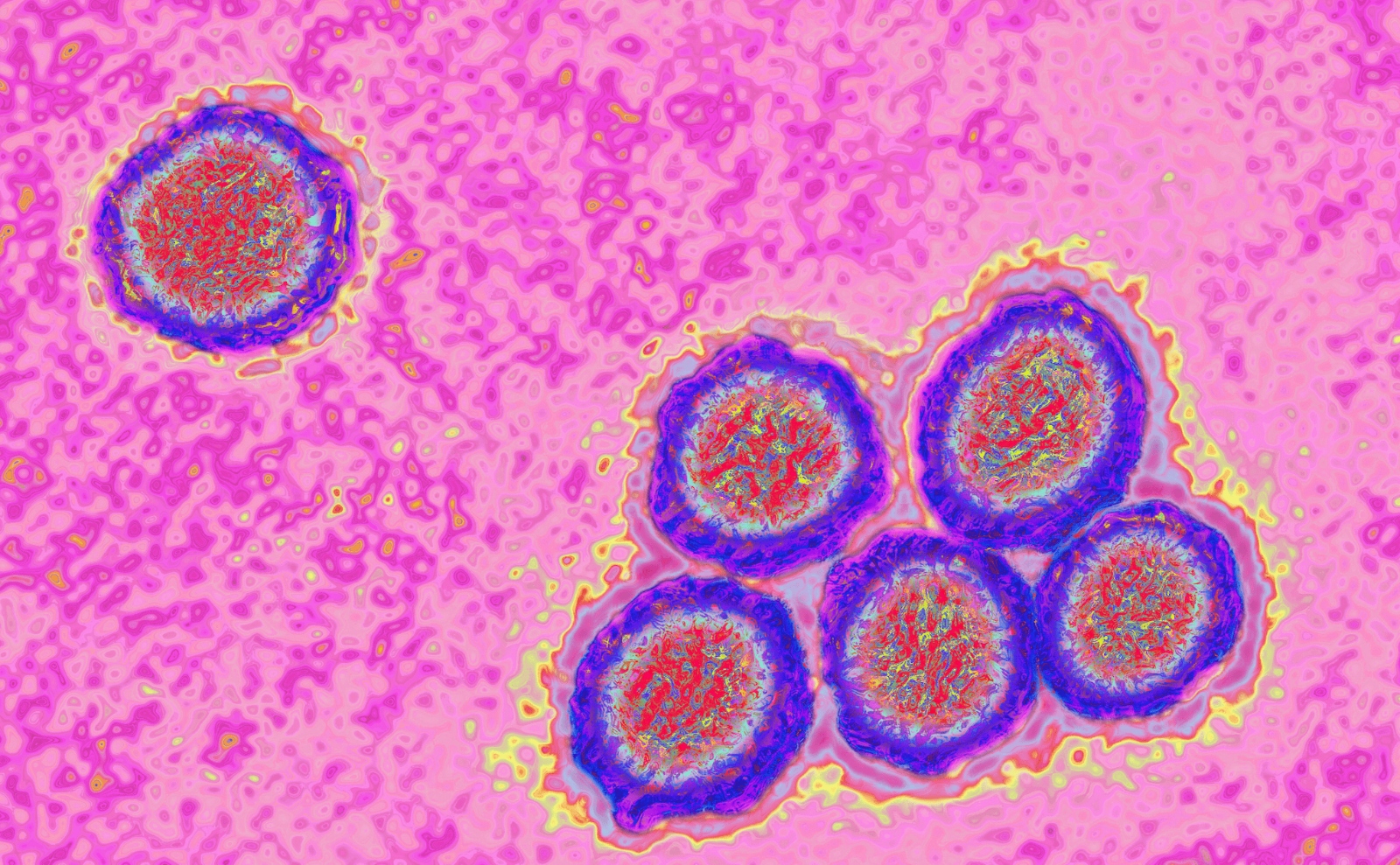

Bacteria

Climate change is helping to spread a bacteria called Vibrio, which proliferates in warm ocean water and causes an illness called vibriosis. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, and a rash that can progress into an infection called necrotizing fasciitis, or flesh-eating disease. Bad cases, usually caused by eating contaminated shellfish, can lead to death. You can also get sick by swimming with an open wound or accidentally splashing contaminated water into a cut.

Under an intermediate warming scenario where temperatures rise up to 2.6 degrees Celsius (4.7 degrees Fahrenheit), climate change-associated cases of vibriosis are expected to rise 51 percent by 2090. Warming ocean temperatures along the coasts of the continental United States are allowing Vibrio to flourish and expand further north, particularly in the Northeast and the West. Three people died in New York and Connecticut this past summer after contracting the illness.

But Vibrio isn’t the only type of bacteria benefiting from rising temperatures. Leptospirosis, an illness caused by a waterborne pathogenic bacteria that can infect humans and other animals, is spreading in Hawai‘i and the U.S.-affiliated Pacific Islands as ocean temperatures rise and tropical storms challenge this region’s water and sanitation infrastructure. Fecal coliform bacteria, which can lead to dysentery, typhoid fever, and hepatitis A, are also a climate-driven risk in this region, according to the report.

Foxes, fungi, and amoebae

The report also identifies some unexpected drivers of illness that are cropping up in states from Texas to Alaska.

In the Southwest, a fungal disease called Valley fever, which occurs when fungal spores take root in people’s lungs and cause painful symptoms such as lumps, rashes, fever, and fatigue, is spreading. As the continental U.S. warms, the fungus will move north into states where it has rarely been seen before, such as Oregon and Washington. If climate change continues completely unabated, cases of the disease will rise 220 percent by the end of the century, according to the report.

In Alaska, rabies is popping up in foxes and other animals, raising concerns about the potential for human cases. There is no cure for rabies and the fatality rate, nearly 100 percent, is the highest of any disease on earth. In the winter spanning 2020 and 2021, Alaska reported 35 cases of rabies in animals, up from an average of four to five cases in the preceding years. Researchers say melting sea ice and changing prey patterns could be reasons for the spike.

Naegleria fowleri, often referred to as the brain-eating amoeba, causes a deadly brain infection when the amoeba gets into the nose canal and, from there, into the brain. A toddler in Arkansas died after contracting the disease playing in a splash pad in September. An adult in Texas also contracted a fatal case of disease this year. Based on these limited cases and other scattered deaths that have occurred in recent years, the authors of the Fifth National Climate Assessment think the disease may be spreading north. “More research is needed,” they write.