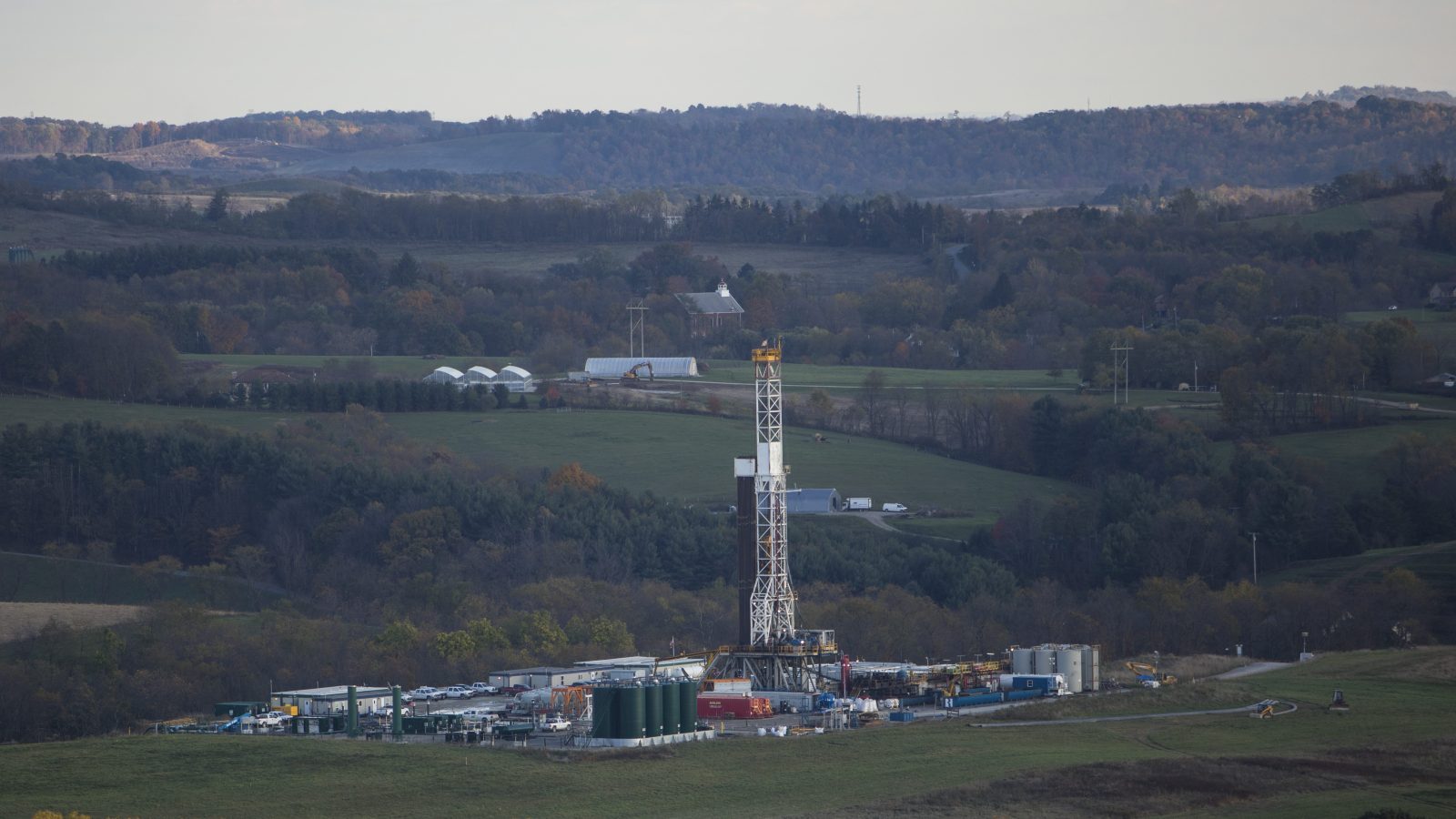

For years, residents of Belmont County in Eastern Ohio suspected something was wrong with their air. Their corner of rural Appalachia was far from the vehicle exhaust and heavy industry of big cities, but many regularly experienced headaches, nausea, and fatigue, as well as trouble breathing. They suspected that fracking operations, which are heavily concentrated in this part of the state, might be releasing toxic compounds into the air.

When monitoring by state air regulators didn’t detect anything out of the ordinary, some residents decided to take matters into their own hands. They installed portable air sensors — which test for pollution by shooting a laser beam into the air and measuring the light that bounces back — throughout the county, thanks to funding and research support from several universities and nonprofit organizations.

The results confirmed some of their worst fears: Air quality in the area frequently exceeded standards set by the World Health Organization, according to a study published last month in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The citizen-run sensors picked up high levels of benzene, toluene, and fine particulate matter, contaminants linked to elevated risks of cancer and heart disease.

The Belmont County project is part of a wave of community air monitoring efforts taking off around the country, from Chicago to St. Louis. In recent years, low-cost air sensors like those deployed in Ohio have become significantly cheaper and easier to use, while more residents have started to realize that federal and state monitoring programs can’t capture the true scope of air pollution in their towns or neighborhoods. These localized projects, in turn, have revealed worrying levels of pollutants in areas that the federal government otherwise deems safe.

Last year, low-cost monitors installed at a convent near Pittsburgh helped pick up emissions of volatile organic compounds, or VOCs – a pollutant not tracked by EPA monitors – near a new ethane cracker plant used in plastics manufacturing that Shell was constructing in the area. Community sensors in San Francisco’s Outer Sunset neighborhood have consistently detected levels of particulate matter that exceed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s average daily exposure standard.

Garima Raheja, a PhD candidate at Columbia University and lead author of the Belmont County study, said she’s been in touch with other community groups, from Louisiana’s Cancer Alley to the Bronx in New York City, to help them design their own air monitoring projects.

“There are attempts to do this all over the world,” Raheja said. “And the more we talk about it, the more we publish, the more we broadcast that it’s happening, it really helps those movements connect to each other.”

Under the Clean Air Act, the EPA is required to monitor the air for certain types of “criteria” pollutants, like particulate matter, ozone, and sulfur dioxide. If levels exceed federal limits, the agency can declare the area in “non-attainment” and require local authorities to bring down air pollution levels. On a large scale, this system has led to drastic improvements in air quality, with levels of the most common pollutants dropping by 78 percent in the 50 years since the Clean Air Act was introduced.

But traditional air monitors are costly and require time, expertise, and laboratory access to use, meaning that regional air quality agencies typically rely on a small number to cover an entire city or county. Belmont County has only three sensors for an area that covers nearly 550 square miles, with hills and valleys that can concentrate pollutants in wildly different amounts depending on the location. The existing monitors, Raheja said, didn’t reflect the “heterogeneity of the different levels of air pollution experienced by people living in different parts of the community.” At the same time, residents have grown increasingly alarmed by the proliferation of fracking in the area, with Ohio’s oil production more than five times higher now than it was a decade ago.

Two local advocacy groups, Concerned Ohio River Residents and the Freshwater Accountability Project, applied to collaborate with the American Geophysical Union’s Thriving Earth Exchange, a program that pairs scientists with communities seeking their expertise. Working with researchers from Columbia University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, they installed 60 low-cost air sensors designed by PurpleAir, a for-profit company, and nearby Carnegie Mellon University in homes, schools, and churches. The sensors, though less precise than the EPA monitors, are simple to use and upload their readings to a real-time map that can be accessed with an internet connection. They also cost tens of thousands of dollars less than EPA monitors.

Over the next two years, the sensors detected spikes in fine particulate matter and VOCs, some of which correlated with increased reports of headaches, nosebleeds, and other health effects from residents. These didn’t show up on the regional EPA monitors, which only take readings at certain times and might not be close enough to catch the worst of the polluted air. Raheja and her team were also able to map plumes of pollution coming from a nearby natural gas plant, showing how wind patterns could influence which homes experienced spikes and when.

Most critically, the devices put a number to the air quality on a hyperlocal level and helped residents understand when it was unhealthy or dangerous, said Lea Harper, managing director of the Freshwater Accountability Project. Prior to the study, many in Belmont County downplayed their own symptoms, feeling that nothing could be done about them. Others denied that fracking – a major economic force in the region – had any negative impact on Belmont’s air quality, Harper said. Finally having numbers gave advocates like her a new tool to organize residents, as well as prepare for potential legal action against the companies emitting these pollutants in the future.

“To have at least some ability to verify and validate people’s concerns has been much more empowering than anything I was able to do before,” Harper said. Using the results, she convinced many residents to install air filters for when pollution levels spike.

With concrete data to support their gut feelings, community members could take action to protect themselves, said Yuri Gorby, a microbiologist and volunteer scientist with the Thriving Earth Exchange. Gorby, who grew up near Belmont County, helped set up the sensors and interpret the results, and was able to develop close connections with residents because of his own roots in the region. One couple in their 70s, Gorby said, called him after they woke up in the middle of the night with headaches; the monitor inside their home showed a spike in VOC levels, and he advised them to leave the house for their own safety.

Raheja said that this kind of partnership between residents and scientists helped differentiate the project from other examples of “citizen science,” when researchers enlist the help of locals to help them gather data, but leave once the results are finalized. These types of studies rarely take into account what the residents themselves want to learn about their surrounding environment. In contrast, “the community pitched this project,” Raheja said. “The goals are set by the community, and we follow suit and help them make it happen.”

The EPA itself has started to embrace citizen science. These projects, according to an EPA spokesperson, “can help fill data gaps and can be important tools for local residents in working with their state, local, or tribal nation governments to improve the quality of the air that we breathe.” One example is the AirNow Fire and Smoke Map, which sources air quality data from nearly 13,000 sensors managed by individuals or local groups. It provides smoke and pollution information during wildfire events to communities that might live far from an official EPA monitor.

Monitoring on its own, though, won’t be enough. Currently, the EPA does not use data from low-cost sensors like PurpleAir to make regulatory decisions, such as declaring that an area is in non-attainment. Raheja said agencies with the power to reduce emissions and penalize polluters need to take the results of studies like the one in Belmont County into consideration, and begin including community members in the decision-making process. Attempts to do so in states like California, where a 2018 law established air monitoring programs that incorporate data from sensors located in environmental justice communities, have so far failed to deliver the results that many advocates pushed for.

Another entrenched problem is the EPA’s own standards for air pollutants, which are less stringent than many health experts believe are necessary to protect human well-being. The World Health Organization, for example, recommends capping annual levels of fine particulate matter at 5 micrograms per cubic meter, while the EPA allows three times that amount. Some types of VOCs, meanwhile, are not regulated by the EPA at all.

“The goal is to reduce these emissions, and the goal is to help the communities breathe better,” Raheja said. “We need to do the science, but we also then need to do the policymaking to change something based on the science.”