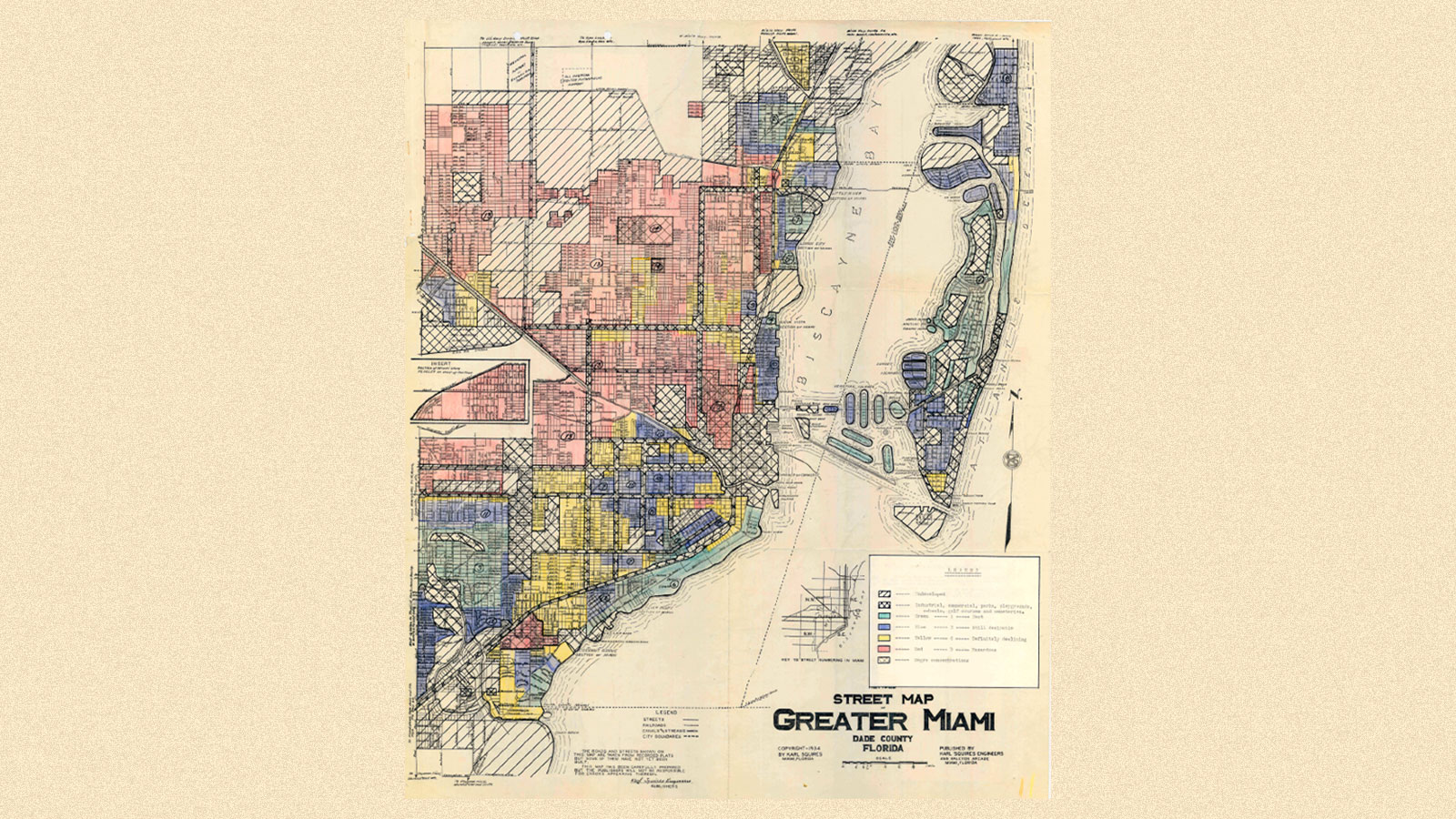

At the height of the Great Depression, when home foreclosures in the United States soared to 1,000 per day, the federal government adopted programs to keep people in their homes and make mortgages more affordable — just not for everybody. To determine who would get assistance, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, created as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, mapped out cities across the country in the 1930s. Appraisers ranked neighborhoods all over the country on a scale from Grade A to Grade D, drawing green lines around the neighborhoods deemed most desirable and red lines around the “hazardous” ones — essentially a code word for where ethnic minorities and especially Black people lived.

Even though “redlining” was banned in 1968, its legacy is still creating problems today, since urban planners saddled these neighborhoods with polluting industrial plants, airports, and highways. Historically redlined neighborhoods have fewer trees than richer neighborhoods and suffer more from air pollution and extreme heat. And according to a recent study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, they are also subject to more noise pollution, often at volumes that pose risks to human health.

Researchers at Colorado State University, along with experts in New Mexico, New Hampshire, and the United Kingdom, analyzed how exposure to transportation noise aligned with maps of historically redlined neighborhoods, looking at the consequences for human health and urban wildlife. They found that the maximum noise levels in neighborhoods coded as Grade D by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation back in the 1930s were 10 times higher than in Grade A neighborhoods, in terms of sound intensity.

While you might expect that the more crowded the city, the louder it would be, the research found that redlining grades predicted noise levels from traffic, trains, and planes even better than population size did. “What was striking to me was how clear those patterns were,” said Sara Bombaci, an author of the study and a professor of conservation biology at Colorado State University. Previous studies have found that noise pollution is worse in Black neighborhoods and in segregated cities as a whole, but the new analysis is the first to look at redlining specifically.

The Environmental Protection Agency recommends that noise levels stay below 70 decibels in order to avoid hearing loss. Nearly all redlined neighborhoods across 83 cities had maximum noise levels above that threshold, according to the study, as did most Grade A through C neighborhoods. Several redlined areas had maximum noise levels above 90 decibels, roughly as loud as a blender or power tools — a threshold that’s associated with hearing damage, higher stress levels, and physical pain. Only a handful of Grade A neighborhoods were exposed to that level of sound.

Not all noise is bad for your health — the sound of crickets, for instance, can reach up to 100 decibels, yet people still fall asleep to it. What stresses people out is “unwanted sound,” according to Erica Walker, an epidemiology professor at Brown University. Unexpected noises can disrupt your sleep and your mood and even trigger a fight-or-flight reaction. “This stress response is the same stress response that you would have if you’re walking down a dark alleyway and out jumps a man with a knife,” Walker said. Confronted with an irritating noise, your body releases stress hormones that put you at greater risk for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and mental health problems.

“Noise today is an artifact of poor urban planning policies,” Walker said, pointing to how governments built major highways right through longstanding Black communities.

According to data provided to Grist, the cities where redlined neighborhoods had the worst noise levels are Miami; New York; Austin, Texas; Chicago; San Francisco; and Denver, in that order. Some of those cities are just loud in general: In Miami and Chicago, even Grade A neighborhoods were subject to maximum noise levels above 95 decibels, Bombaci said.

Columbus, Georgia, had the quietest redlined neighborhoods, followed by Davenport, Iowa, and Jackson, Mississippi.

The researchers used data from the Department of Transportation that only considered noise from traffic, rail, and aviation. If noise from industry and construction were included, Bombaci suspects that the separation between Grade A and Grade D neighborhoods would be even more distinct.

Noise is often viewed as a first-world problem, Walker said, or simply a sacrifice of living near where things are happening. But there are plenty of ways that cities can reduce noise pollution, including lowering speed limits on roads and using quieter types of pavement to decrease friction with tires. Some cities, like Washington, D.C, have banned gas-powered leaf blowers, silencing their 80-decibel drone. The New York City Council is considering bills to minimize the blare of sirens on emergency vehicles.

But it’s not easy to move a highway or airport. “Once we go back and look at how urban planning and policies contributed to this, then we need to do justice,” Walker said. “And then we need to make sure that going forward, that we aren’t implementing policies and procedures without considering noise.”