This story was produced by Grist and co-published with Alaska Public Media.

People in Alaska’s rugged Interior have long known the hills surrounding the Native Village of Tetlin hid gold. As tribal member Kevin Gunter grew up, his elders told him such riches should be left alone. Nothing good would come of digging them up, they warned. Now, Gunter fears what might happen as an open-pit mine comes to his tribe’s land.

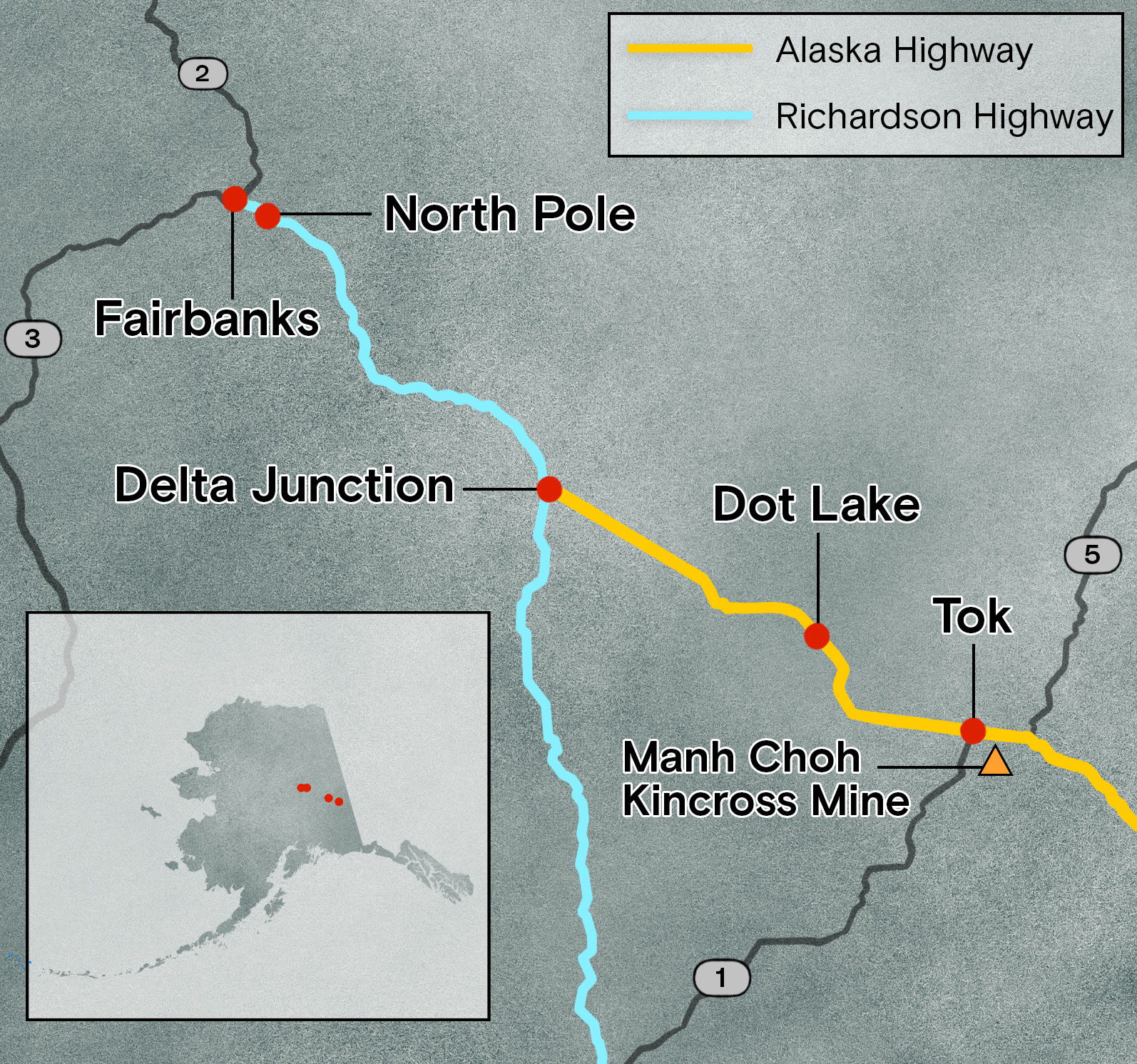

Kinross, the majority owner and operator of the project, plans to haul the ore roughly 250 miles on public roads to a mill at another mine, called Fort Knox, outside Fairbanks. To learn more about the company’s plans for the new mine, named Manh Choh, Gunter took a job as a senior electrician at Fort Knox about a year ago. He soon grew frustrated by the culture. “Nobody’s doing any quality control,” he said. “They won’t plan a job. And they won’t work the plan.”

That didn’t inspire confidence in Kinross sending 80-ton trucks rumbling down the primary highway linking Fairbanks to Canada and the Lower 48. So Gunter started digging into how and why his tribe approved the company’s lease for the land. He and other tribal officials found what they allege is a series of questionable background deals, corruption, and self-serving arrangements by the former chief and current tribal leaders.

In a written statement to Grist, Kinross insists that the company has acted in good faith and within the rights provided by its lease, while investing in things like a road to the community. But the Tetlin Native Corporation, a for-profit business owned by tribal shareholders, claims it is the rightful owner of some of the land — and that it was not party to the negotiations and did not approve the lease. It alleges that the mineral lease broke tribal laws. The corporation hopes to establish its claim to the land. This may call the lease with the tribal council into question, potentially delaying, or even stopping, the project.

The corporation’s allegations are one of two looming legal actions that could scuttle Kinross’ plans. In late October, a group of citizens called Committee for Safe Communities filed a lawsuit claiming the project violates state transportation regulations. It has asked the state to pause the truck haul pending an independent review of public safety concerns Grist previously reported.

Gunter grappled with his decision to speak out. As a single father, he worried about the repercussions for his family. The project has been contentious, as some locals cheer the jobs it promises, while others worry about the safety and environmental impacts. But one night while making his daughter dinner, he decided he had to take action. “I just thought, what kind of a s****y father would I be if I just let this happen to her,” he said.

He felt a duty to his tribe to reveal what he’d found. “When you tell the truth, it becomes a part of your past,” he added. “But if you lie, that becomes part of your future. And we’re gonna be seeing everybody’s future here real soon.”

Until 1968, vast, unbroken tundra stretched across the northern reaches of Alaska, windblown hummocks resting beneath sweeps of curving sky. Then British Petroleum — the company now known as BP — struck oil in Prudhoe Bay. That lucrative discovery created a huge problem: Building an 800-mile pipeline to a shipping terminal on the other side of the state required figuring out who owned the land it would traverse.

Much of it belonged to Native communities who didn’t rely on written documents like deeds and titles. As oil companies pushed the state, established just nine years earlier, to quickly settle the issue and get the pipeline started, activists like Iñupiaq politician Eben Hopson pointed out how long it would take to litigate claims with hundreds of villages. “This is our land,” Hopson declared in a public hearing in 1969, as the fight unfolded. “If you want it, pay fair value for it.”

That tension led to the federal Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. The law attempted to secure better treatment for the Indigenous peoples of Alaska than those in the Lower 48 had received. The federal government transferred 44 million acres — almost 10 percent of the state — to for-profit Alaska Native companies that serve tribal shareholders. These business ventures aimed to facilitate the economic development of Native communities and provide greater control over their natural resources.

The Tetlin Native Corporation received 743,147 acres. Unlike many other village corporations, it retained the rights to subsurface resources like minerals. While the corporation is responsible for the tribe’s business investments, the tribe’s chief and council govern Tetlin, overseeing things like the tribal court and social services. Ideally, the two entities work together on the community’s behalf, but things grew complicated when their leadership overlapped.

Donald Adams, whom everyone called Danny, was named Tetlin’s chief in 1989. He was also the president of the tribal corporation. Adams sported a wispy goatee, a love of cards, and a passion for sharing Tetlin’s culture. He was known to hunt ducks in the spring and live off the land. “You have to have that link to where you came from, and what your culture means to you,” he once told a filmmaker.

In 1994, Chief Adams led the council in applying for a casino license. The National Indian Gaming Commission denied the application because the corporation, not the council, owned the land. The following year, Adams’ attorney suggested transferring the tribe’s land to solve that problem. A majority of the corporation’s roughly 125 shareholders was required by state law to approve this move, but they never did so.

Nevertheless, in 1996, Adams transferred 643,147 acres to the council, leaving the corporation with 100,000 acres that was under litigation after a wildfire. The move rendered the corporation insolvent, leading dissenting shareholders to sue for “breach of fiduciary duties.” In 2006, the state Supreme Court ruled that Adams abused his authority in the “wrongful transfer.” The corporation removed Adams, but the tribal council allowed him to remain chief.

Before a new deed could be drawn up restoring the corporation’s ownership of the land, Adams met Brad Juneau, a clean-cut businessman fond of purple ties who owned a prospecting company in Texas. In June 2008, Adams brought Juneau to a tribal council meeting, where Juneau proposed exploring for minerals, gas, and oil. Roy David, a council member at the time, and others expressed wariness at the idea and requested more information. He believed Juneau should answer the council’s questions before any further action was taken.

But the following month, Adams unilaterally signed a mineral lease for 780,000 acres — more land than Congress ever allocated to the corporation — during a closed-door meeting with Juneau’s exploration company. Adams “manipulated and controlled all transactions outside of the council’s knowledge,” David later said in notarized testimony.

Although tribal law requires a council majority to approve all contracts, David and at least one other council member said they never knew about the lease. He began hearing rumors about something happening with a mining company, and was disturbed when Adams refused to provide details. Frustrated by the stonewalling, he resigned from the tribal council.

Juneau went on to form a joint mining venture with several companies, eventually including Kinross, the Toronto-based mining business that now manages the operation. The details of the contract remained a closely guarded secret until 2015, when it was filed with the state Department of Natural Resources. When he finally saw it, David said, “the mineral lease from the first page on had false information.”

In the midst of all this turmoil, Roy David walked into the Wings of Healing Church in Fairbanks. The pastor, David Flenaugh, often turned to Scripture when his congregation was facing trouble. “Hell and destruction are never full; So the eyes of man are never satisfied,” he said, quoting Proverbs 27. But if greed isn’t serving you, he said, “we need to do something different.”

Flenaugh’s sermon resonated with Roy David, who invited the minister to Tetlin. Flenaugh, who runs a construction company, was struck by the lack of playgrounds there and offered to build some. Over time, he grew more involved with the community, eventually becoming the corporation’s general manager in 2011, paying its bills out of his own pocket. As he dug into the corporation’s finances to help it return to solvency, he discovered it couldn’t borrow money or use its land for collateral because the title remained clouded by Adams’ transfer. “It became our goal to clean that up,” Flenaugh said. He hired researcher Loretta Smith to help.

It turned out the mining deal Adams brokered had included an initial payment of $50,000 to Tetlin for negotiating expenses. The SEC filings don’t show who received that money, and the contract expressly stated “Tetlin shall not be responsible to [Brad] Juneau to account for the expense payment.” The mining venture named one of the project’s most promising areas the “Chief Danny Prospect.” Chief Adams also approved a finder’s fee to Rickey William Hendry, another Texan who brought Juneau to Tetlin in the first place: As a “friend of the tribe,” Hendry and his heirs would receive 10 percent of any future net profits from mineral exploration on the land in perpetuity. It is unclear whether anyone else knew at the time that the tribe had surrendered so much of its profits. As Grist previously reported, Tetlin will receive royalties of just 3 to 5 percent from Manh Choh, though similar endeavors elsewhere in Alaska often give tribes much higher returns, as well as partial ownership. Red Dog, for example, is a large zinc mine leased from the Iñupiat in northwest Alaska, who now receive 35 percent of its net profits.

Juneau’s company Contango ORE — which now owns 30 percent of the Manh Choh mine — later hired Adams as a consultant for $60,000 a year, citing his “special knowledge and experience with governmental affairs and tribal affairs issues.” Roy David later said in an affidavit that, “[Neither] I, nor any other council member were aware of this and would never have consented as this practice is prohibited under our governing laws.” Although the contract said that none of Adams’ work would relate to a “certain mineral lease” he had approved, it allowed for discretionary bonuses — payments which totalled an additional $80,000. All told, the payments to Adams came to more than $250,000. Chief Adams may have needed the money: Before he died in 2015, he had a federal $157,042 tax lien, according to the IRS.

Pieces of mining machinery drive through Fort Knox, Alaska. Courtesy of Kinross Gold

A conveyer belt, left, carries ore in Fort Knox, Alaska. Kinross plans to transport ore more than 250 miles from the Manh Choh mining site, right, to Fort Knox for processing. Courtesy of Kinross Gold

When Adams passed away, the tribe elected a man named Michael Sam to be chief, and a slate of new members joined the council. But fresh leadership didn’t help resolve the dispute with the tribal corporation. When Flenaugh sat down with Chief Sam in 2016, meeting notes show Sam didn’t know much about the joint venture, though he “stressed that it was his preference to see the miners leave.” Subsequent conversations proved difficult, and it appeared his attitude changed. The corporation’s emails and calls went unanswered. When Flenaugh sent a certified letter to the council, Kristie Charlie, the tribal administrator, returned it to the postmaster unopened. “We have no idea as to why our mail was refused,” Flenaugh later wrote to Sam, who did not respond to Grist’s interview requests.

According to Kevin Gunter, Sam recently has been seen driving new trucks and recreational vehicles and taking vacations that suggest to him an unusual increase in income. “Tetlin is a small village, but when tribal members see something out of place — word will spread,” Gunter wrote in an open letter he distributed among tribal members in October. “Is it possible the KINROSS mining partnership is paying Chief Sam for his tribal position like they did Chief Adams?”

Kinross declined to be interviewed for this story, but in a statement to Alaska Public Media, Grist’s publishing partner, four days after publication, Kinross stated, “For the past two years, Sam has worked as a heavy equipment operator for Qayak, a general contractor at the mine. As such, he has earned an income from the Manh Choh project.” The company also said “it has never paid Chief Sam a single penny.”

Gunter is now collecting signatures from tribal members, asking Kinross to publicly reveal if they are providing any compensation to Chief Sam or any other tribal officer. Gunter claims tribal council officers visited the homes of those who signed his letter, in what he considers an attempt to intimidate them into removing their names from the petition.

Gunter, who spent his own money consulting lawyers as he tried to parse the tribal council’s dealings, was furious. “You’re gonna sell your whole people out for a $90,000 pick-up truck? And give away all their resources just so you can feel special for a moment?” He scoffs. “Good Lord, you’d live forever if you just fought for your people — they’d always remember you. But that’s just not the choice that was taken.” If the mine’s going to move forward, he says the tribe should at least benefit. “Right now, we’re in generational poverty, and it’s just a dirty cycle,” he said. “It becomes — mentally, physically, spiritually — who you are.”

Questions about the Tetlin Tribal Council’s financial dealings go beyond the Kinross lease. Federal records show that in 2020 and 2021, the council received nearly $10 million in federal grants and contracts, including $4,841,963 in coronavirus relief funds for roughly 380 members. As the pandemic stretched on, tribal members repeatedly called the Tetlin Native Corporation, asking for help tracking down their checks. Since the tribal council received and distributed that cash, the corporation didn’t know anything about it. Under federal law, anyone who disburses more than $750,000 of federal assistance in a fiscal year must obtain an audit. Based on data from the Federal Audit Clearinghouse, it appears the council has never done so. “What happened to the money?” Gunter asked.

Tribal members aren’t the only ones posing such questions of the council; in May, the federal Office of Family Violence Prevention and Services sent the Tetlin Native Corporation a delinquent notice regarding a grant awarded to the council. Flenaugh told the agency that the corporation was not involved, and asked what services the grant was meant to provide. “Tribal shareholders living in Tetlin, when asked, report knowing little to nothing about your grant,” he wrote in a response to the office’s inquiry.

With these financial inconsistencies as a backdrop, the Tetlin Native Corporation is trying to raise awareness about how the mining companies have portrayed their relationship with the tribal council. The joint venture misrepresented the tribal council to both the state and the SEC as a village corporation — something anyone familiar with ANSCA knows is not possible. The corporation alleges this “misappropriation of the Corporation’s ANSCA status [was] to entice investors,” who are often leery of dealing with tribal governments, given the sovereign laws and courts that entails.

When confronted, the joint mining venture wrote a letter saying it “inadvertently suggest[ed]” that status and amending its permit application — directly contradicting the language in its own lease. At that point, though, “they already got what they wanted, and did what they wanted to do,” Smith said. In a statement sent to Grist, the tribal council, which supports the mine and wants the project to proceed, said, “The Tribe reserves all of its legal rights and remedies with respect to the false and defamatory statements” by the corporation.

But the biggest problem may be much more fundamental. Eight years ago, the Tetlin Native Corporation conducted a licensed survey of the 100,000 acres it retained after the council’s 1996 takeover. It alleges some of the Manh Choh mine is on land it still owns. A surveyor the corporation hired earlier this year concurred. Indeed, in 2012, the joint venture that Kinross has since joined admitted in an SEC filing, “We have no assurance of title to our Properties.”

Kinross, of course, disagrees, and told Grist in a written statement “the Manh Choh mine is entirely on this Tetlin [Council]-owned land.” In a 2021 letter to Flenaugh, a lawyer for the mining venture denied any encroachment on any of “the lands reserved to the TNCorp in the 1996 Deed.” In its statement to Grist, Kinross said the council “owns in fee the surface and subsurface rights of their land” and that “[o]ur mineral lease with the Native Village of Tetlin provides access to explore and develop mineral resources on Tetlin Tribal lands.” It also said the venture has acted in good faith with all existing agreements with the tribal council, and that it has invested $600,000 in amenities for the area.

Yet the Tetlin Native Corporation insists that that 1996 deed is defective because the council and the corporation were still disputing the land rights when the lease was signed. Smith says this is an example of “tortious interference,” a legal term for when a third party wrongfully interferes in a business relationship. The tribal corporation wants to quiet the title, a legal process that would clearly establish its ownership of at least the 100,000 acres everyone agrees it retains, and possibly revisiting the wrongful transfer of the 643,147 acres to the council..

In part because its financial resources are limited — Flenaugh continues paying the corporation’s expenses — the corporation has had difficulty asserting its claims. Many lawyers have conflicts of interests; the state of Alaska has invested in the project, and it’s difficult to find a law firm that hasn’t previously worked for the state. Some environmental groups that might normally get involved have stayed quiet, not wanting to tread on tribal sovereignty or dampen fundraising by appearing to take sides against a tribe. But the impression that Tetlin was united in its approval of the mine is mistaken, Gunter said. “We keep our shame. We may talk about it with each other, but we won’t — culturally, we just don’t really go after the leader.”

On a chilly day this fall, Barbara Schuhmann was watching her granddaughter at home in Fairbanks while fielding calls and emails about Manh Choh. A retired lawyer, Schuhmann’s concerns about the ore haul’s threat to public safety led her to join Tracy Charles-Smith, the president of Dot Lake, another tribe on the trucking route, and Patrice Lee, a retired teacher who’s been fighting chronic air pollution in Fairbanks. They founded the non-profit Committee for Safe Communities to demand greater safety and accountability for the project. “All we’re doing is asking a court to order the DOT to follow the law, and its own rules,” Schuhmann said. In October, the Committee sued the Alaska Department of Transportation, seeking an injunction requiring the agency to follow all state regulations before allowing Kinross to haul ore on public roads.

As Grist previously reported, the agency plans to use federal highway funds for road and bridge construction and improvements to accommodate the Kinross trucks — without conducting an environmental impact statement. The Committee also alleges that the 95-foot long trucks violate state restrictions governing vehicle length on roads that aren’t specifically designated for industrial use. A state consultant hired to conduct an independent review found that, contrary to previous DOT statements, bridges between the mine and Fort Knox cannot withstand the mining traffic. In some cases, the trucks will be twice as heavy as the federal maximum vehicle weight. The winding highway only has two lanes, and in some places the massive vehicles’ top speed will be about half the posted speed limit, creating dangerous traffic situations.

The DOT did not follow the necessary procedures and public process for adding these bridge replacements to the statewide transportation plan. As a result, this fall, the Federal Highway Administration told the agency to remove them — and froze federal funds for 2024 highway projects for the entire state until this is resolved. “This is extremely rare that a state DOT has ever been in this situation,” says Jackson Fox, executive director of Fairbanks Area Surface Transportation Planning. “It’s a pretty significant issue.” The local planning committee voted Nov. 8 to reject adding the bridge replacements to the DOT’s transportation plans, saying it pushed more urgent projects down the priority list — a move which will make it more difficult to resolve the DOT’s problem with the federal agency.

Darrel VanDeWeg, who recently resigned as the chief of the Salcha Fire and Rescue department, said “anytime somebody puts more vehicles on the road, that’s concerning.” The majority of the first-responders on the route are volunteers. As more commercial vehicles drive on the state’s roads, the risks grow. “It’s not just this road, it’s all the roads in Alaska,” he said. “I just don’t know what the limit is.”

Meanwhile, this fall Governor Mike Dunleavy named DOT Commissioner Ryan Anderson to the board of trustees for the Alaska Permanent Fund, which has invested $10 million in Manh Choh. “Like he doesn’t have enough to do, running the transportation system and the railroad and airports and ferry system and the roads and bridges,” Schuhmann said with a laugh.

Despite the concerns of people like Schuhmann and Gunter, and the pending lawsuits, the mine is slated to begin production by the end of the year. There is less and less time for those who oppose the project to make their voices heard. And though he died eight years ago, Adams’ influence still looms. In a video filmed shortly before he passed away, Adams sat in a camo jacket in a rough-hewn log cabin, reflecting on being a Tetlin tribal member in changing times. “Our everyday, simple goals [are] being challenged by this lack of knowing who we are and where we should be,” he said.

Though he sees things differently, the same questions spur Gunter. For him, the Manh Choh project and the council’s signing away the land is another in a long list of examples of how his tribe has been slowly pushed from its home and its ways of being in the world. “There’s no people without the land. It’s who they are,” he said, part proud, part frustrated at having to explain. “And a lot has already been lost.”

Editor’s note, December 6, 2023: This story has been updated to include an additional statement from Kinross.

Lois Parshley is an award-winning investigative journalist. Follow her reporting @loisparshley on social media.