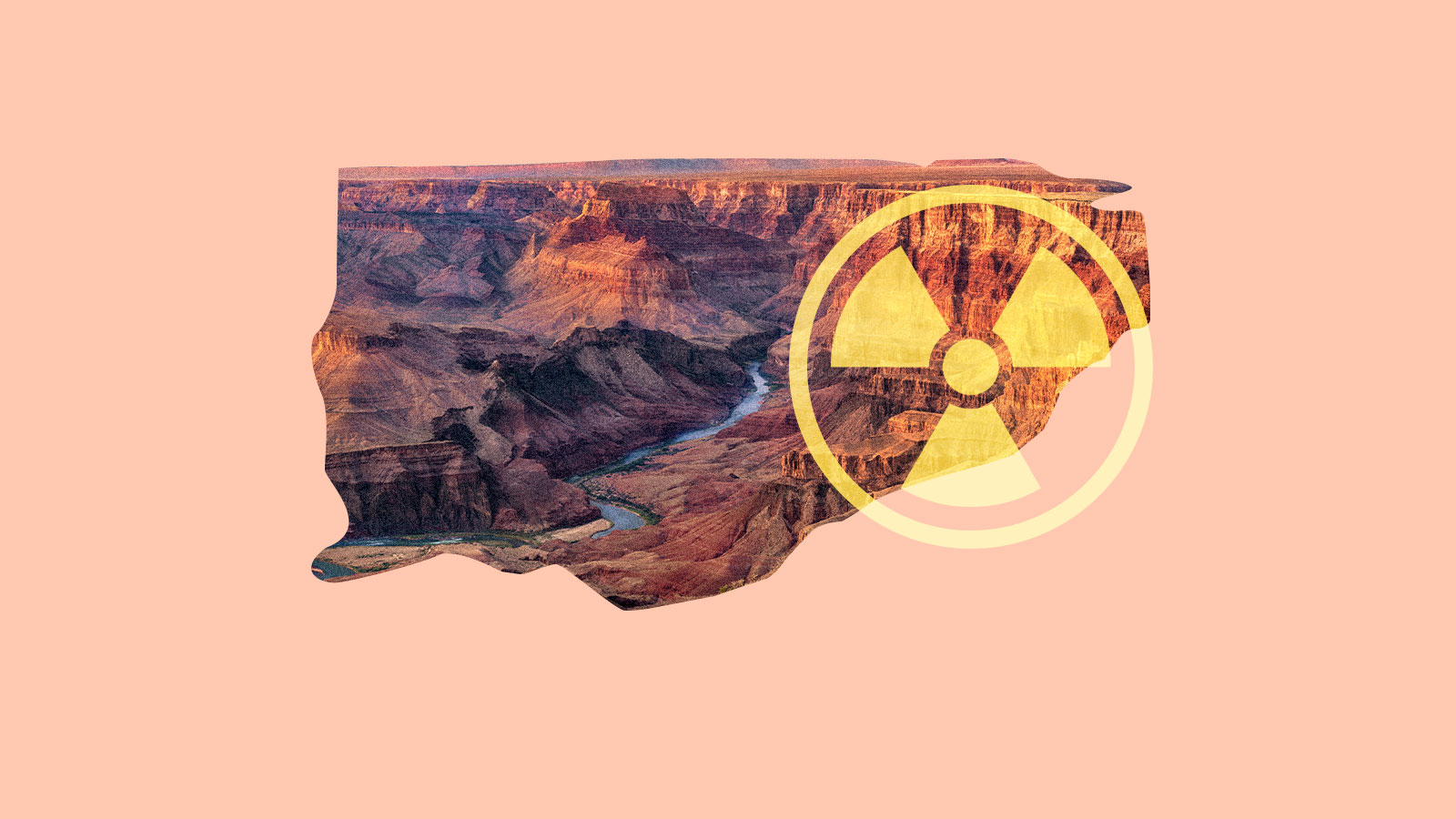

On a windy day last August, President Joe Biden signed a proclamation protecting the canyons, cliffs, and plateaus surrounding the Grand Canyon National Park, nearly a million acres abutting the Navajo Nation and Havasupai Indian Reservation.

Biden said the new national monument was part of his commitment to Native peoples to protect their sacred lands. “Preserving the Grand Canyon as a national park was used to deny Indigenous people full access to their homelands,” Biden acknowledged.

To Carletta Tilousi, one of the leaders of the Havasupai Tribe who have called the Grand Canyon home for more than 800 years, Biden’s presence and his words felt momentous. “Finally, the small voices of Indigenous people have been heard in the White House,” she thought.

But she knew the fight was not over. The monument prevented hundreds of mining claims, but two uranium mines were grandfathered in, in part due to an 1872 law that guaranteed their right to operate. And now, nearly 40 years after first gaining permission to extract uranium, a Colorado-based company is cashing in.

On December 21, Energy Fuels Resources announced it had started mining uranium at Pinyon Plain Mine, which lies within the borders of the national monument and has lain dormant until now.

The company’s decision was influenced by favorable federal policies supporting nuclear energy, high prices for uranium ore, and greater demand for domestic nuclear fuel. The U.S. purchased 12 percent of its uranium from Russia in 2022, and there’s growing political pressure to stop those imports in the face of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

The 17-acre Pinyon Plain Mine is 12 miles from the Grand Canyon, six miles from the Grand Canyon National Park, and four miles north of Red Butte, a site sacred to the Havasupai people where Biden gave his August address. The Havasupai Tribe sued along with environmental groups to prevent the mine from starting production, but lost its case in 2022.

Energy Fuels plans to operate the mine for three years to six years and estimates that it will generate 2 million pounds of uranium, says Curtis Moore, senior vice president of marketing and corporate development.

“After mining operations are complete, the Pinyon Plain area will be fully reclaimed and returned to its natural state,” the company has promised. “There will be virtually no evidence a mine ever occupied the site.”

Amber Reimondo is doubtful. She’s energy director at the Grand Canyon Trust, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the Grand Canyon and the Colorado Plateau that sued to prevent the mine along with the Havasupai Tribe, and says uranium mining threatens the aquifer in the greater Grand Canyon area.

“Of course we want to reduce carbon emissions, [but] we want to make sure that we do that in a way that doesn’t continue to impact Indigenous communities,” she said.

According to Reimondo, water systems in the landscape are complex and interconnected. Energy Fuels’ mining process involves drilling a mine shaft through shallow aquifers into uranium deposits, and water flows into the shaft, mixing with the ore, before being pumped out. The concern is that contaminated water will be mixed back into the groundwater.

To date, the company has removed about 49 million gallons of water from the shaft, leaving it to evaporate in an aboveground pool or sharing it with local ranchers for their cattle once treated to EPA standards. Reimondo worries that water could eventually contaminate not only drinking water sources but the creeks and waterfalls throughout the Grand Canyon.

“It’s really, really difficult for researchers to understand exactly what that risk is, because the region is so highly fractured and because we don’t know exactly where water flows to and from,” Reimondo said.

Energy Fuels’ Curtis Moore thinks that concern is overblown. He said that the water that the company pumps out of the shaft is already highly concentrated in uranium because it has been in contact with the rocks long before their mining operations started.

“Their implication is that we are contaminating groundwater, which is simply false — it’s naturally not appropriate for human consumption,” he said. He pointed to a 2022 permit from the state of Arizona that concluded the geology of the mine site — like the slope of the land and type of rock — are “expected to prevent any potential impacts to groundwater resulting from mining operations.”

A separate 2021 study by scientists from the U.S. Geological Society found that the type of uranium mining conducted at Pinyon Plain Mine has historically had no confirmed effects on uranium levels in the groundwater sampled in and around the Grand Canyon. But the study also noted that it could take many years for any related pollution to reach the groundwater.

That potential for negative long-term effects are what Havasupai Tribe members are concerned about. Dianna Uqualla, a Havasupai Tribal Council member, says if there’s pollution in the aquifer years from now, she doubts anyone will take responsibility.

“Who’s going to pay the price?” she asked. “Who’s going to be the one to say, ‘Yeah, I did it’? I don’t think anybody’s going to do that. They’re just going to say, ‘Well, one less tribe, and we’re happy for that,’ is what the non-Natives will probably think.”

Uqualla is familiar with the long history of damage wrought by uranium mining on Native lands. In the nearby Navajo Nation, years of uranium mining caused lung cancer and a decadeslong struggle to get compensation. The mining was so widely harmful that the Navajo Nation has banned the transport of radioactive and related materials through their lands.

Despite that ban, once mined, the uranium ore from Pinyon Plain Mine will be trucked to the White Mesa Mill in southern Utah along state and federal highways, including through Navajo Nation. Navajo President Buu Nygren has implored the federal government to step in on the matter.

Once the ore makes it to White Mesa Mill, the company will extract natural uranium concentrate from the uranium ore, before selling the powder to U.S. nuclear power facilities, which arrange for the concentrate to be sent to other facilities for conversion and enrichment.

Moore says that uranium mining is much safer and better regulated than it was decades ago, and trucking the uranium ore is safe. Uqualla and Tilousi remain skeptical.

Tilousi wishes that Congress would update the 1872 mining law that allowed Energy Fuels to continue operating a mine on a national monument. That’s something the Biden administration has recommended too, in part because the law allows companies to hold mining rights for long periods of time, which sows distrust among local communities including Indigenous peoples.

Tilousi is hopeful reform can happen but doesn’t expect it anytime soon.

“As a Native American living in this country, we are always fighting something,” Tilousi said. “It seems like we are always fighting for our existence.”