Five miles doesn’t seem far on the vast, windblown plains of the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana. There’s a high point on the dirt road leading to Danny Barcus’ ranch on the east side of the reservation, tucked within the Two Medicine River valley. When Barcus drives up there, as he did one morning in May, he can see about that far in any direction, the peaks of Glacier National Park rising in the distance.

That’s how Barcus, a member of the Blackfeet tribe himself, spotted the buffalo — nearly 200 by his estimate — where they weren’t supposed to be that spring day, their chocolate-brown humps peppering one of his grass-green wheat fields. He called his dogs, hopped in his off-road vehicle, and sped over. The buffalo had crashed through his barbed wire fence and were nibbling on the winter wheat he was growing for his cattle. Over the last year, a punishing drought had settled over the plains, and Barcus had begun to feel helpless, worrying over bills he wasn’t sure he could pay. “My savings account is the grass I saved last year,” he said. “I can’t afford to feed it to the neighbor’s buffalo.”

In this case, Barcus’ neighbor is the Blackfeet tribe, which keeps buffalo on the pasture it owns next to his property for part of the year. The Blackfeet herd is one of many across the continent, part of a growing movement to return buffalo, once nearly extinct, to tribal lands. For many Plains tribes like the Blackfeet, buffalo used to be the foundation of diet, commerce, and spiritual life. Bringing them back represents an effort to reconnect with that heritage and, in doing so, restore endangered grasslands. But managing the wild, ever-roaming animals is complicated by the fact that the land is now criss-crossed with contemporary borders between states, national parks, and reservations.

Barcus and the dogs, Pepper and Tucker, guided the runaway buffalo back onto the tribe’s land. Then he began repairing the downed fence: a broken post here, a snarled wire there. Poor management was the root of the problem, Barcus thought. The tribe had let the herd grow too big, so the animals had eaten their way through the pasture, and when there was no food left, they ambled onto Barcus’ ranch where there was plenty more.

It wasn’t that he had a problem with buffalo. “We understand the spirituality behind the buffalo,” said Barcus, speaking of himself and his wife. Two years ago, the couple allowed the Horn Society, a spiritual organization, to host a Sun Dance on their land; buffalo are a central symbol in the Blackfeet’s most important religious ceremony. But it was a different matter when they started eating into Barcus’ business. “We also have families, employees, and our own animals to take care of,” he said.

Danny and Cindy Barcus, left pose for a photo near green grassy fields. Right, their dogs, Pepper and Tucker, rest after a long day. Courtesy Danny Barcus

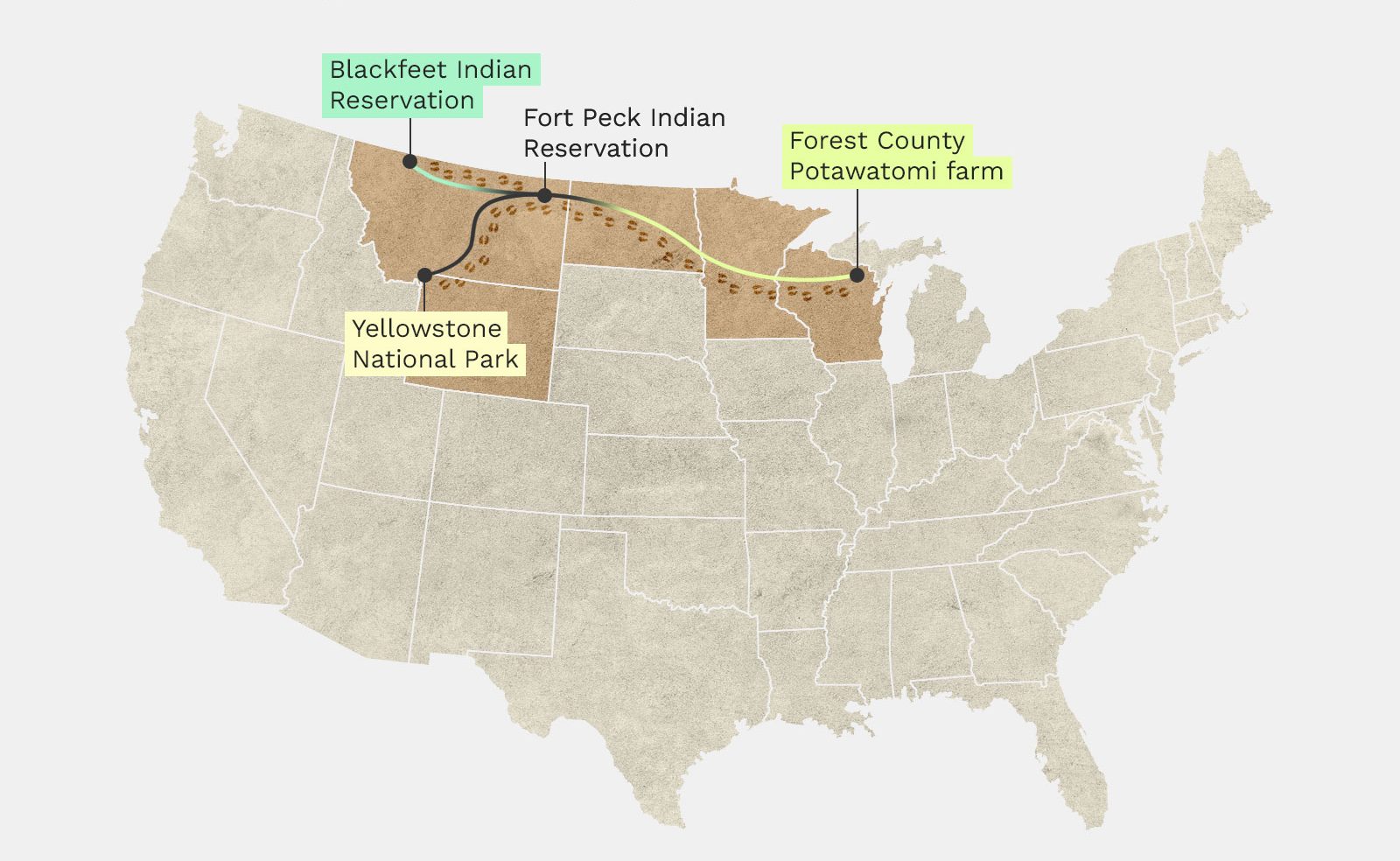

A six-hour drive south of the reservation, another herd of bison rambled through Yellowstone National Park, eating, on the move, unaware of where they should or shouldn’t be. The scientific name for the species is Bison bison, but many Native Americans use “buffalo,” a remnant of the 17th-century French fur traders who likened the creatures to the buffalo found in Africa and Asia. Yellowstone bison are central to the tribal restoration effort: Animals from the park help populate herds like the Blackfeet’s. After bison were driven to near-extinction in the late 1800s, a handful of the remaining several hundred were taken to Yellowstone for protection. Their lineage represents the last true plains bison in North America, since ranchers interbred many bison with cattle in the following years. As a result, the animals from Yellowstone are prized above all.

“Those animals were descendants of the animals that provided for our people,” said Troy Heinert, a member of the Rosebud Sioux and executive director of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, a federally chartered organization that coordinates the return of buffalo to Indian Country. “There’s a connection there between Indigenous people and those animals that can’t be replicated in other places.”

As summers grow hotter and drier and rainfall more erratic, restoring buffalo to tribal lands could provide people with a healthy source of food and boost the resilience of plains ecosystems. “When you talk about buffalo restoration, it’s also land restoration, water resource restoration, and cultural revitalization,” said Heinert, who is also a Democratic state senator in South Dakota. “This is so much bigger than just the animal itself.”

The effort will be shaped by what happens next at Yellowstone National Park, which is working on an update to a 22-year-old bison management plan — a process that will determine how many animals can live in the park and how many can be transferred to tribes. But that plan must balance growth with a slew of complications: a nasty bacterial disease, cattle ranchers and politicians in Montana, and the bison’s very own nature to wander.

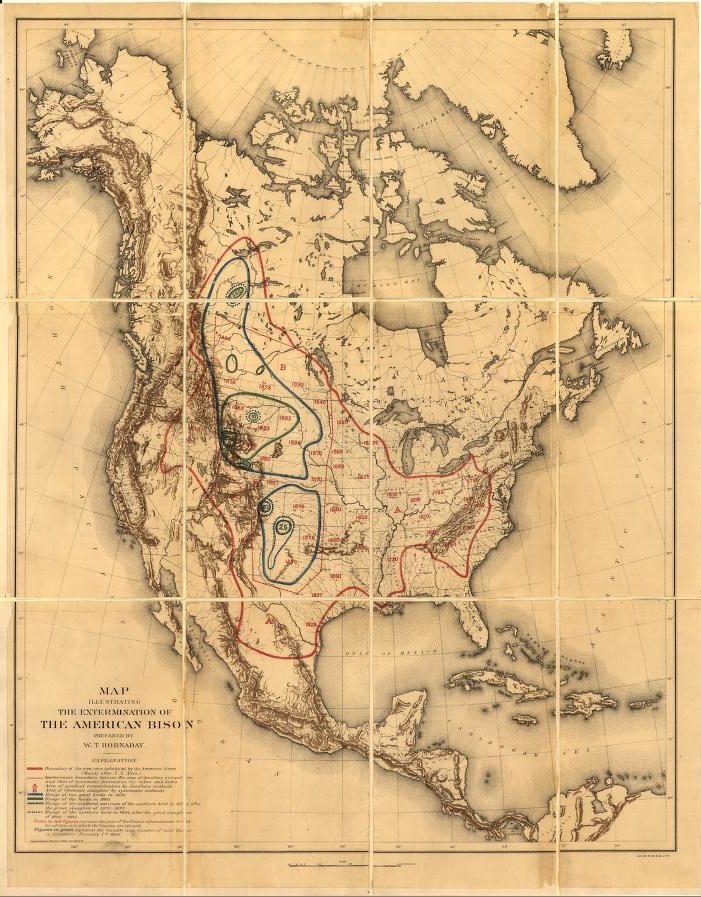

For hundreds of thousands of years, bison thundered across the continent in the tens of millions, from the dry plains of northern Mexico to the snow-covered grasslands of south-central Canada. The animals shaped the land and lives around them: By grazing, they cleared the way for a diverse mix of plants to grow and altered the path of wildfires; their droppings propelled nutrient cycles that fed a host of smaller critters; their cast-off winter coats provided insulation for the nests of burrowing owls and mountain plovers. And, for generations, Indigenous peoples hunted them across the prairies, relying on buffalo as a source of food, clothing, tools, and ceremonial objects. When Europeans arrived in North America, bison could be found across the width of the continent.

Colonization set the bison’s swift decline in motion. Livestock belonging to European immigrants overgrazed and eroded the grasslands where bison fed. European-introduced horses made bison-hunting more efficient for Plains tribes, which had previously hunted on foot and been forced from their traditional hunting territory, while booming fur and hide markets overseas encouraged indiscriminate hunting in the 19th century. The demand meant hide hunters killed millions of bison each year. Cycles of drought added even more pressure as the bison’s territory shrank.

By the late 1860s, the U.S. Army was encouraging this mass slaughter. Killing bison would undo the economies of entire Indigenous nations, part of the Army’s strategy to push Native Americans onto reservations and clear the way for railroads and westward settlement. In 1868, Major General Phillip Sheridan, tasked with forcibly relocating Great Plains tribes, wrote to a fellow general that the best strategy was to “make them poor by the destruction of their stock, and then settle them on the lands allotted to them.”

What had begun as a trend toward overhunting escalated into state-sponsored eradication. The bison population collapsed over the next decade. By 1884, just a few hundred remained in the wild.

Today, there are roughly 400,000 bison across North America, with the vast majority being raised as livestock. Since their history is intertwined with the prairies, ecologists view their re-introduction as key to restoring the country’s grasslands, an estimated half of which has already been lost to cattle, crops, and development. More bison roaming the land would mean the return of wallows, bowls in the dirt that can stretch more than 10 feet across. They’re created when the 2,000-pound animals roll and toss themselves on the ground.

Wallowing is a useful form of pest control: It keeps the number of flies and ticks down on individual animals. But it also sets off a cascade of events that benefit local wildlife. Sticky seeds often hitch a ride on bison coats, and when the animals roll around, the seeds fall and sprout into a carpet of deep-rooted grasses that lock carbon in the earth. In the spring, the dusty wallows collect water, providing a breeding ground for frogs and salamanders in a landscape where ponds are otherwise scarce.

The ecological benefits of wallows can persist for decades. Jason Baldes, a member of the Eastern Shoshone who now manages the tribal buffalo program for the National Wildlife Federation, remembers riding with his father through the Wind River Mountain Range as a child and spotting relic wallows from buffalo long gone. They were overgrown with brush and wildflowers, but the dips in the land were still easy to spot. Later, as a graduate student at Montana State University, Baldes studied old wallows and their relationship with culturally significant plants. He found that several species — yarrow, tall bluebells, and arnica — tended to thrive in them.

Baldes, who is also the secretary for the InterTribal Buffalo Council, thinks a shift in the way the United States governs land is necessary for the widespread return of buffalo. Conventional farming, the cattle industry, oil and gas companies — “these imposed systems have not been beneficial for tribal communities,” he said. “It’s probably time to try something different that incorporates more of our values and beliefs. That would be to more holistically manage our lands. We do that by restoring the keystone species.”

Since bison once lived across such a wide range of conditions, ecologists think they may be well suited for some of the challenges brought on by climate change. That’s in stark contrast to cattle, which were brought to North America by the Spanish in the 1500s. Cattle have since replaced bison’s dominance on the landscape, with an estimated 30 million living in the U.S. today. Cattle seek shade and water at much lower temperatures than bison. They tend to find a good spot to eat and stay put, mowing the grass down to a nub. Bison, which evolved on the treeless plains, are much more comfortable at high temperatures. When they cool off, they prefer to catch a hilltop breeze. They’re not inclined to overgraze because they’re always moving. As a result, they do much less damage to plants and delicate streams and rivers.

That’s not to say bison are immune to heat. Over the last 40,000 years of gradual warming, their average body size has shrunk by around 36 percent, said Jeff Martin, the research director at South Dakota State University’s Center of Excellence for Bison Studies, who has studied fossils to understand how the animals have changed over time. By contrast, cattle have swelled about that much over the last 30 years — a product of hormones, diet, and selective breeding for size. A larger animal is increasingly vulnerable to heat stress, which became sorely evident this summer after a grueling heatwave killed thousands of cattle in Kansas.

“A smaller body is thrifty in drought and heat conditions,” Martin said. “Bison, as they become smaller and smaller, become thriftier and may be able to survive some of these harsh environments.”

Given all these advantages, researchers believe bison could support ecosystems and communities well into the future — even one defined by a volatile climate. “Bison have seen warming and cooling,” Martin said. “They’ve seen drought, they’ve seen wet years. Their genetic fingerprints have the potential to reconcile those environmental differences, if we allow them to do so.” That, of course, is the hard part. As bison numbers climb, the wild animals are returning to a continent, now riddled with fences, highways, and state borders, that has gotten used to operating without them.

For most of the last century, the Yellowstone bison, recovering from near-extinction, rarely wandered beyond the park. But as the herds grew, they began to adopt their ancient migratory behavior. Every winter, they trekked from the high plateaus of the park down to the foothills and river valleys of West Yellowstone and Gardiner, Montana. At these lower elevations, less snow on the ground means food is easier to find.

By the 1990s, however, the population had climbed above 4,000 — up from 23 animals in the park nearly a century before. Ranchers and state officials in Montana saw roaming bison as an existential threat to cattle, the state’s top agricultural commodity, because bison carry brucellosis, a bacterial disease that can cause hoofed animals, including cattle, to miscarry. Montana’s brucellosis-free status was at risk: Losing it would force the government to spend millions on testing the cattle sent to other states.

Montana sued the National Park Service in 1995, and it took a court-mediated settlement to create the Interagency Bison Management Plan five years later. The plan set up a partnership between state, federal, and tribal agencies, which would, according to the agreement, “maintain a wild, free-ranging population of bison and address the risk of brucellosis transmission to protect the economic interest and viability of the livestock industry in Montana.”

The arrangement set a target population of 3,000 and requires that the partners agree on how many animals will be culled each year (it ranges from 300 to 900). Yellowstone has a few ways to manage the herd. Mostly, it ships surplus animals to slaughter. A handful of tribes have treaty rights to hunt buffalo once the animals have stepped beyond the park borders. Yellowstone also uses a transfer program — after 30 years of lobbying from the InterTribal Buffalo Council — in which bison are sent to herds on designated lands. Before they are moved, the animals must quarantine for up to three years to make sure they’re brucellosis-free.

In January, the National Park Service announced it would begin the process of updating Yellowstone’s 22-year-old bison management program. According to the federal agency, the science behind the agreement is outdated. For one thing, there’s never been a case of bison-to-cattle brucellosis, even though thousands of bison have crossed into Montana over the years. When the disease has spilled from wildlife to livestock, researchers say elk, which freely roam the area around Yellowstone, are the more likely culprit.

The Park Service now believes Yellowstone can safely sustain even bigger herds. Increasing the number of bison in the park would enhance the animal’s ability to fill its ecological roles while continuing to support tribal transfer and hunting programs.

“We are working to ultimately reduce reliance on shipment to slaughter,” Yellowstone’s superintendent, Cam Sholly, told the Associated Press. The park says its new program will guide how the animals are managed only within the park. If the herds are allowed to grow, however, that likely means more bison will venture outside its borders.

Over the years, the interagency partners have allowed Yellowstone’s bison numbers to exceed their original target. At 6,000 animals this summer, the population is higher than it’s ever been. “If you look at it cumulatively over time, we’ve made some really good strides, and we’ve achieved our objectives as a group,” Sholly said during an interagency meeting in April. “I think it is important that we do everything in our powers to continue that progress and continue to make this group relevant.” (The park declined requests for an interview with Sholly.)

The Park Service laid out a number of options for the next era of management. One sticks to the status quo: a range of 3,500 to 5,000 animals. The most ambitious would cease slaughter entirely, aiming for a population of 8,000, create more opportunities for hunting, and send more bison to tribes. The InterTribal Buffalo Council, made up of 76 member nations across 20 states, is lobbying for more transfers — to keep fostering herds like the Blackfeet’s, next to Danny Barcus’ ranch.

“Our ultimate goal, and our goal always has been, is to get as many live buffalo out of Yellowstone and to tribal lands as we can,” said Troy Heinert, the InterTribal Buffalo Council’s executive director.

Even if the park adopts a more ambitious target, major obstacles remain to expanding the transfer program. An estimated 60 percent of Yellowstone bison have been exposed to brucellosis, which first came from cattle that were brought to the area and was transmitted to local wildlife in the early 1900s. Baldes, from the National Wildlife Federation, says that means tribes need to maximize the remaining 40 percent. But Yellowstone’s quarantine facility can only handle around 80 animals, while an average of 800 bison are slaughtered each winter. “Right now, there’s animals going to slaughter indiscriminate of whether they have brucellosis,” he said. “That’s an atrocity.”

Yellowstone recently obtained funds to expand its capacity to 200. Tribes also have the ability to quarantine around 600 animals at a state-of-the-art facility on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeast Montana. At the moment, however, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services, which oversees the country’s brucellosis eradication program, only allows it to be used for the last year of quarantine — so-called “assurance testing” that comes after two years of repeated tests. The Council has advocated for Fort Peck to host the earlier phases, which would help alleviate the bottleneck posed by Yellowstone’s smaller center.

In February, Montana’s Republican governor, Greg Gianforte, rejected all of the Park Service’s proposals and told the agency to go back to the drawing board, Yellowstone Public Radio reported. The population increases, Gianforte wrote, “are absurd and unsupported by both science and lay observation.” Even the status quo option, he continued, has “proven too much for [Yellowstone] to handle.” Sholly, Yellowstone’s superintendent, offered to work with the state to develop another alternative.

Yellowstone has been frank about the messiness of bison politics. “Many people don’t like the fact that animals from a national park are sent to slaughter. We don’t like it either,” its website says. “But we cannot force adjacent states to tolerate more migrating bison.”

Some 600 miles northeast of Yellowstone, sprawled over wide, blooming prairies, the Fort Peck quarantine facility and its roughly 400-head herd are points of pride for Suzanne Turnbull, a Dakota member of the buffalo advocacy group Pté, named after the Dakota-Lakota word for female buffalo. Pté’s latest project is a four-mile trail that would wind through the 15,000-acre pasture, dotted with benches and storytelling stations where visitors could learn about the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux tribes’ relationship with buffalo. (The benches won’t be secured so that the animals, which like to scratch their heads on rocks and trees, can rub against the wood without breaking them.)

Turnbull says she feels a strong spiritual connection to the animals. She had been at the pasture on a cold and blustery day in November 2014, when a group of Yellowstone buffalo arrived in semitrucks to join the growing Fort Peck herd. A kindergarten teacher at the time, Turnbull said she’d felt called to take the day off to greet the new arrivals. The field buzzed as reporters readied their cameras and tribal members sang. “You’re back,” she thought, as she watched their approach. “We’ll take care of you so we can all get well together.” The trucks backed into the pasture, and the animals bolted out, their hooves clanging on the metal ramp before they sprinted away.

As part of her work with Pté, Turnbull often takes students and visitors, as well as her nieces and nephews, to the pasture so they can experience being with the wild, hulking animals like she has. “I see them as medicine,” she said, thinking of her own troubles, which she’d only found peace with through her spiritual practice. “I see them serving a purpose to bring back the foundation for storytelling, of our culture and language, our values, our kinship.”

On the other side of Montana, at the Blackfeet Reservation, Joe Kipp, chairperson of the Blackfeet Nation Stock Growers Association, also has a longstanding connection to the reintroduction effort. In the 1980s, he’d been involved with bringing the first wild buffalo — surplus animals from Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota — to the Blackfeet Reservation. These days, he and his wife make the drive south to Yellowstone every winter to hunt the animals; Kipp’s wife is diabetic, and the only meat she eats is bison. (Compared to beef, bison has more protein and minerals, and much less fat and cholesterol.)

Still, Kipp is unhappy with how the tribe has managed its herd in an austere landscape where many make their living raising cattle. Ranchers deal with ferocious wind storms, bitter winters, crippling droughts: Business margins are tight. He’s heard from plenty of disgruntled ranchers like Danny Barcus, who rent grazing lands for their livestock — the current rate for a cow-calf pair is around $40 a month — only to have the tribe’s buffalo break in and eat the grass intended for their cattle. “It gets to be a sore point pretty fast,” Kipp said.

Kipp worries what will happen now that bison are being considered for protection under the Endangered Species Act, a move he fears would undermine his treaty hunting rights. He’s also content with Yellowstone’s current management and doesn’t see the need to expand the park’s herd. “People envision, ‘Oh, we want bison that are running across the landscape like before,’” he said. “But we didn’t have 50,000-pound trucks and trains running and cars and all these things. It’s a beautiful concept, but I don’t think it’s based upon reality.”

This spring, Kipp, Barcus, and other Blackfeet cattle ranchers met with their tribal council and asked them to make changes to the herd’s management. After years of frustration, they felt the council had been receptive to their concerns, and this summer, the tribe began a new culling program to manage its herd.

Follow bison’s historic range east, into the heart of America’s dairyland, and you’ll find a small farm tucked in Wisconsin’s Northwoods where some Yellowstone bison have found a home. After quarantining at Fort Peck, they arrived at the Forest County Potawatomi farm through an InterTribal Buffalo Council transfer in 2020. The Forest County Potawatomi is one of the Council’s easternmost members, and it has embraced bison as a way to provide its people with a healthy source of protein.

On a bright July day, the farm’s manager, Dave Cronauer, followed a worn path between two pastures surrounded by a wall of pine. Bugs buzzed in the tall grass and wildflowers waved in the breeze. Half the fields were for cattle, the other half for bison. Once the animals had chewed the turf down to a few inches, they would be guided to the next paddock in order to give the plants a chance to regrow and deepen their roots, a practice known as rotational grazing.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in the food system, it also “proved how valuable we were,” Cronauer said. The tribe opened its farm store in March 2020 at the start of the pandemic, when shelves at neighboring grocery stores were bare from people stocking up on goods. But the farm store still had meat to sell. The ability of local, small-scale operations like theirs to withstand wider shocks, Cronauer said, could prove to be vital for a future in which warming temperatures and extreme weather will strain conventional agriculture and cattle farming.

Cronauer went searching for the cattle. Bison and cattle were fundamentally different animals, he explained. Tap a bison on the head and it charges you; tap a cow on the head and it retreats. Bison are still wild, and he admired them for it. He spotted the cattle. They were difficult to see from the path, but on that summer day, they had congregated at the water, taking sanctuary in the shade under a thicket of trees. Across the way, the small herd of bison bathed in the heat of the afternoon sun, wagging their tails.

This story has been updated to distinguish between plains bison and another subspecies.