Photo by Verena Radulovic.

“See that, see that?! … Oooh, something is going on. They are spraying tonight.” A large cylindrical truck whooshed past us.

I am driving along a state road with Becky, a local activist, who is narrating from behind the wheel. “I once stuck around to see them spray and I had to turn the car around and get out of there, the smell was so overpowering.”

We pull over and I hop out to get a close-up look at the orange groves. I am in California’s Central Valley, America’s fruit basket, where agriculture is king.

Becky Quintana is waiting patiently in the car for me as I crouch down to inspect an orange tree. The leathery green leaves were splashed with white pesticide residue, like a Jackson Pollack canvas would be. It is early December, close to the holidays, one would be forgiven for mistaking the white splotches that covered the trees for Christmas flocking. But it turns out it’s like this year round — the chemical flecks a reminder of the high economic stakes involved in delivering an end product that is shiny, bright, and perfectly spherical.

‘There’s a lot riding on it.” Becky explains. “The fruit pickers bring them to the warehouses where the oranges are washed and waxed to look the way you see them in the supermarket. But most of the time,” she nods towards the fields, “they don’t come off the tree looking like that.”

Decades of applied pesticides and fertilizers have delivered high yield, immaculate-looking fruit to many of the supermarkets in the U.S. and to the far corners of the globe, but not without a local cost. Heavy pesticide and fertilizer use in Central Valley orchards that produce household staples such as oranges, peaches, nectarines, grapes, olives, and walnuts has contaminated local community drinking water.

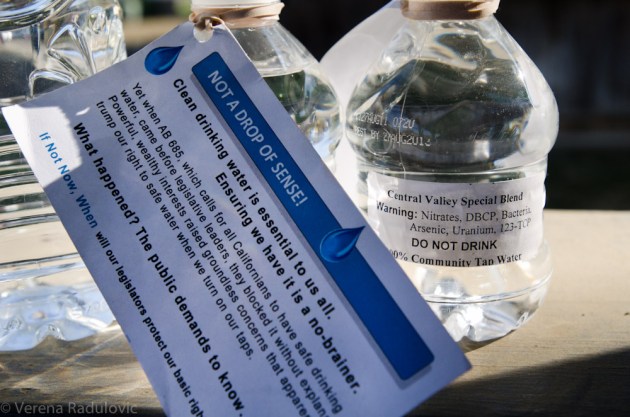

But pesticides and fertilizers are only part of the problem. The primary groundwater contaminant in the region is nitrate, which can also be traced back to Central Valley’s other reigning ruler: Dairy. Interspersed between the acres of golden fruit, behemoth factories house hundreds, sometimes thousands, of cows. This combination of fertilizers, animal factory waste and old, leaky septic systems cause high levels of nitrate that exceed state and federal health standards and can cause death in infants and cancer in adults. The groundwater is also infused with arsenic, DBCP, dangerous levels of chlorine, and bacteria — all of which cause short and long-term illnesses.

Valeriana, a local resident from Tooleville, in her kitchen. (Photo by Verena Radulovic.)

Years ago, my good friend Laurel Firestone co-founded an organization called the Community Water Center (CWC) to bring attention to the water contamination in the region and to advocate for change. I finally visited her and learned more about the impacts of CWC’s work.

She picked me up from the Fresno airport late in the afternoon. By the time we headed south to her home, the sun had already departed the sky. As we drove along the inky highway, a sudden stench, the kind that exercises your gag reflexes, filled the car.

“Dairies,” she said, smiling as we drove alongside one. “Sometimes you can see the manure practically spilling out of the pens onto the road, there is so much of it.”

“I think we should have a scratch and sniff sticker to hand out so others can really experience what it is like to live near one,” said Susana De Anda, CWC’s other co-founder.

So, what does contaminated drinking water look like? Frighteningly, in most cases, no different from safe drinking water. The tap water in Laurel’s kitchen in Visalia, Calif., looked clear and inviting but was laced with 123 Tricholoropropane, a carcinogen. Bottled water is a fixture in almost every home, regardless of income level, yet those who are impacted the hardest are usually low-income Latinos, mostly farmworker immigrants who are the backbone of the area’s agricultural labor force. Almost 20 percent of the population lives in poverty and many residents spend up to a fifth of their income on bottled water, which is in addition to the $60 a month they must spend to have contaminated “drinking water” delivered to their home in the first place. In some cases, residents pay an additional $70 monthly water fee for sewage.

“My kids used to get rashes after taking a shower,” relayed Veronica Mendoza, a local resident and activist from Cutler. And even if you don’t break out in welts after bathing, “you are still inhaling the toxins through the steam of the shower,” said Rose Francis, an attorney at CWC. To make matters worse, as Becky noted, many people think that boiling the water will rid it of nitrates when in fact doing so triples the concentration.

Veronica in her home, preparing dinner. (Photo by Verena Radulovic.)

The difference between water delivery systems intended for crops and those intended for people is stark. Take the town of Seville as an example. Within the same two square miles, one reservoir for crop irrigation is a wide human-made river filled with clear water ready to be dispersed by an automated dam. The water delivery systems for homes in this particular community, while recently retrofitted, is still surrounded by thigh-high weeds leading to a dirty stream, where makeshift PVC piping inches along the muddy, shallow bottom.

Reservoir intended for crops, not residents. (Photo by Verena Radulovic.)

View of local drinking water delivery system in Seville. (Photo by Verena Radulovic.)

Drinking water pipe with unfunded infrastructure applications in the bacground. (Photo by Verena Radulovic.)

The drinking water infrastructure in such communities is often expensive to retrofit. Many towns have decentralized septic systems, which are cumbersome and costly to link to a more centralized water delivery system — or simply costly to replace. Since water infrastructure projects are so politically charged, marginalized communities often find their drinking water improvement projects tangled in the bureaucratic fray. It can take years to get a project approved.

CWC has stepped in at all stages of effort to improve drinking water quality in the Central Valley, from testifying to policymakers to community organizing to working to get local projects funded. CWC’s work is especially challenging because of the delicate social and economic relationship between the agricultural industry and local communities whose jobs depend on it.

Messaging as part of the Community Water Center's recent campaign. (Photo by Verena Radulovic.)

In the five years since CWC opened its doors, small wins have started to emerge that are significant for creating lasting solutions to some of these entrenched problems. CWC staff told me they are beginning to see changes in the way Big Ag approaches the issue of contaminated drinking water and the way residents come together to advocate for changes to improve their livelihoods.

While I was flying home and had time to digest what I saw, two things stood out to me. First, I was struck by how residents who lived in towns with contaminated drinking water were not afraid to work with CWC and advocate for change, despite the fact that they, or their families and neighbors were often undocumented workers. Second, I wondered whether or not we consumers, who are far removed from seeing the firsthand impacts of how our food is grown, would change our purchasing habits if we really knew the full story. As soon as it was time for me to go to the grocery store; this time I veered straight for the organic section.

A version of this post originally appeared on Verena Radulovic’s blog.