Datu Kaylo Bontolan, an Indigenous Manobo leader in the Philippines, was killed during a military assault in northern Mindanao in April 2019. For decades, the Talaingod-Manobo peoples have fought against industrial companies pushing for commercial logging and mining on their land. As industry moved in, so did the military. Bontolan was one of the 43 land and environmental activists killed in the country last year.

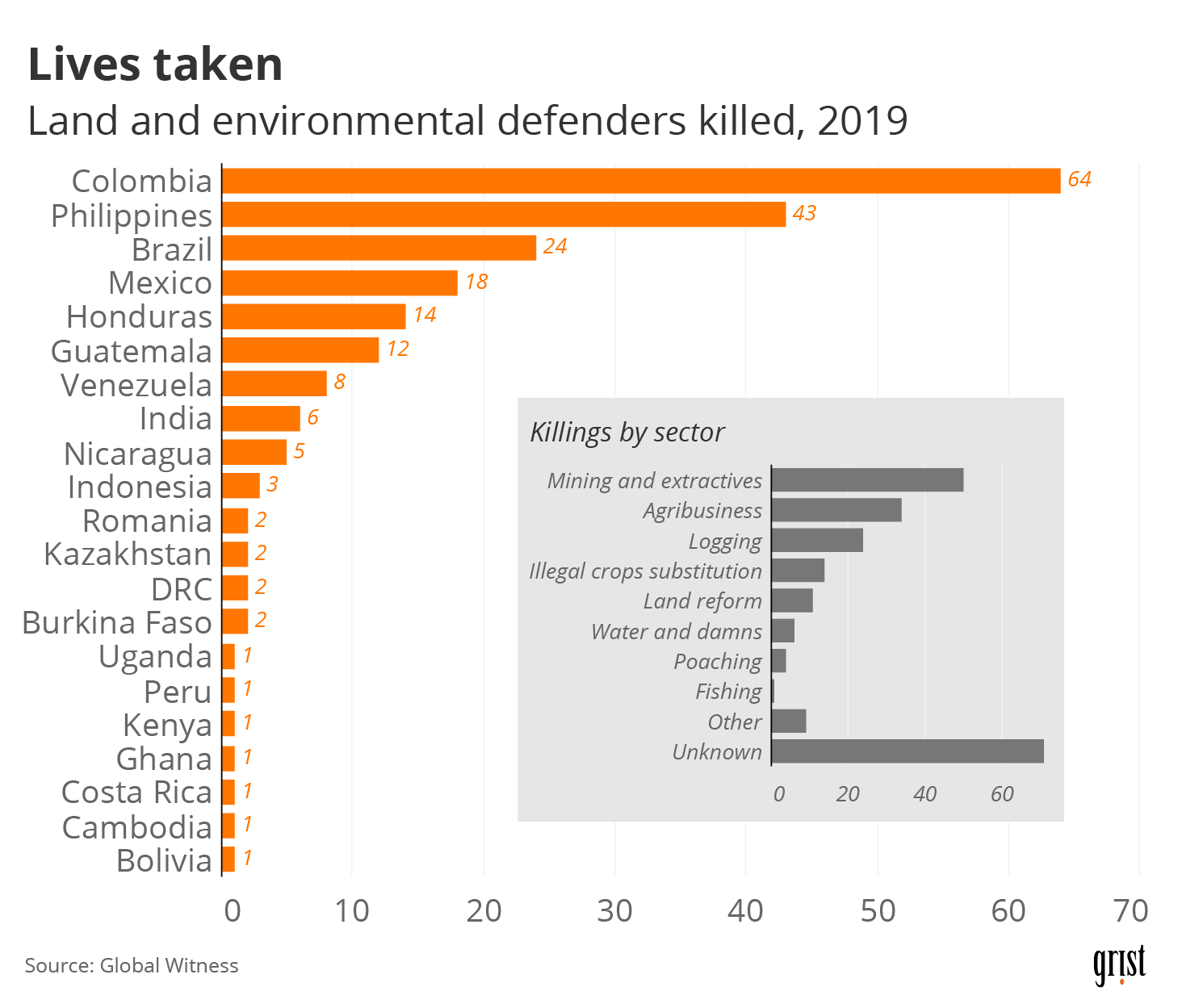

A comprehensive new report from the human rights and environmental watchdog Global Witness found that about 212 land and environmental defenders were killed in 2019 worldwide — a nearly 30 percent rise over 2018 data. The Philippines and Colombia were two of the deadliest countries for environmental activists. More than half of the total reported killings last year took place in those two countries. More than two-thirds of the killings took place in Latin America, which has consistently ranked as the deadliest region overall. The countries with the highest number of killings per capita were Honduras, Colombia, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and the Philippines. About 40 percent of victims were from Indigenous communities, while over 10 percent of defenders killed were women.

The mining industry continues to drive most of the deadliest attacks on environmental activists like Bontolan — about 50 defenders were killed in mining-related conflicts in 2019. Agribusiness and logging were also major sources of conflict. While Global Witness has been documenting environmental attacks since 2012, the group noted that their data almost certainly doesn’t capture the full scope of the problem, because many parts of the world are restricted and difficult to monitor.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

When Francia Márquez was meeting with other environmental activists in the Colombian town of Lomitas in May 2019, they were attacked by armed military men. Although a grenade went off, her group managed to escape. Last year, 64 defenders were killed in Colombia, a total that accounts for 30 percent of killings globally. In addition, the United Nations documented a roughly 50 percent surge in the killings of female activists between 2018 and 2019. According to the report, women are more likely to face violent and abusive tactics than men.

“The attack that we leaders were victim to yesterday in the afternoon invites us to continue working towards peace in our territory,” Márquez said on Twitter the day after her attack, according to the report. “There has already been too much bloodshed.”

The Philippines appears to be the deadliest place in Asia when it comes to attacks against environmental activists. For years, Filipinos have suffered rising temperatures, landslides, and deadly typhoons. No one feels the impacts of these climate disasters more than the country’s Indigenous peoples, including the Talaingod-Manobo tribe. On top of extreme weather events, the country’s rainforests are being razed for mineral extraction and private profit, destroying biodiversity and fueling climate change. The country’s president, Rodrigo Duterte, has called environmental activists “terrorists.”

The Philippine island of Mindanao has always been a military hotspot. According to the report, almost half of all Filipino environmental defenders killed last year lived on Mindanao, a trend that escalated under Duterte’s presidency. As violence against defenders in the Philippines intensifies, Indigenous schools — which are teaching children to protect their culture and their ancestral land — are under attack from the government. In October 2019, the country’s education department ordered some of these schools to shutter, alleging that the schools are linked with “rebels and terrorists.”

“For all Indigenous people around the world, our culture is rooted in our land,” Rius Valle, a spokesperson for Save Our Schools Network, a nonprofit working to defend Indigenous children’s right to education, told Global Witness. “If these lands are taken away from us, it will not just hurt our tribe and culture, but also our future. That is why the creation of our Indigenous schools is an expression to defend our ancestral land and the environment.”

The United Nations Human Rights Council recently published a report that concluded that the Duterte regime’s “overarching focus on public order and national security” — which includes his unending war on drugs and terrorism — has come “often at the expense of human rights.” A new anti-terror bill, which Duterte signed into law earlier this month, is one of the most controversial examples due to the law’s vague and expansive definitions of terrorism. Filipinos worry that the new legislation could be used to target and arrest government critics, especially environmental activists and journalists who are holding power to account.

When it comes to protecting the land and resources that stand between the world and climate catastrophe, environmental defenders — many of them Indigenous — have been the first line of defense for decades. As climate change accelerates, it looks like these activists will continue to face greater and greater risks.