A veil of dust covers the windowsills of Ray Kidd’s home. Outside, in his backyard, particles coat a lemon tree, sticking to the fruit’s pimpled, yellow skin.

“Diesel pollution,” says the 72-year-old Kidd, who has lived in West Oakland since 1973. “It’s just pervasive.” Across town, close to Lake Merritt — a more affluent part of the city — his mother’s backyard lemon tree grows untarnished.

West Oakland sits directly across the water from San Francisco, putting it effectively in the center of the Bay Area. It’s bounded on all sides by freeways — the 880, 980, and 580 — and hugs the Port of Oakland. The bustling docks hold the distinction of being the city’s economic heartbeat, and its worst enemy.

Adjacent to the port is the former Oakland Army Base. The outpost was once “a city within the city,” says community activist Margaret Gordon, who lives nearby. It provided jobs and services, giving residents a reason to look past the diesel fog that spewed into the air from the base, the port, and the trucks that served each.

The base shuttered in 1999. For more than a decade, both the port and the city of Oakland, which divided the land, have contemplated how to use the 310 acres — twice the area of the Washington Mall. The city has considered a Costco, a casino, and an auto mall. At one point the famous Wayans brothers even proposed a movie studio and amusement park.

The city and port eventually settled on a mix of warehouse complexes and shipping infrastructure that will expand the capacity of the port — currently the fifth busiest in the country.

Google Earth

Many residents, including Kidd, saw the redevelopment as an opportunity to invest in West Oakland, where more than 30 percent of the residents live in poverty. “It seemed like the most reasonable thing to do,” says Kidd, who is part of the West Oakland Community Advisory Group.

But more warehouses and shipping mean more trucks, and that all leads to more pollution. Other residents opposed a plan that presented further risks to their health; West Oakland already has some of the highest asthma rates in the state.

Now that construction has started, it might be too late, says Brian Beveridge, who has lived in the area since being driven out of San Francisco by rising rents in the late ’90s. Local activists say their concerns about the redevelopment project continue to fall on deaf ears.

“Having a seat at the table doesn’t really mean anything,” Beveridge says, if decision-makers don’t listen. “That just means they let you in the room.”

This spring, the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project, a community group cofounded in 2004 by Beveridge and Margaret Gordon, reached its breaking point.

In April, the group filed a federal civil rights complaint against the city and the port.

Aided by attorneys at Earthjustice, the group alleged that the city of Oakland has, for decades, systematically ignored input from West Oakland residents, favoring industry over the community’s health.

Under Title VI of the U.S. Civil Rights Act, entities that receive money from the federal government, like the port and the city, cannot discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin. The Environmental Indicators Project claims that both the port and Oakland have violated that tenet by neglecting the concerns of residents in this historically African American enclave.

Eighty-five percent of West Oakland’s approximately 40,000 residents are people of color. For decades, they have coped with the fine diesel soot on their windows, fruit trees, and, more importantly, in their bodies. The number of emergency room visits due to asthma in West Oakland is nearly two times the rate of Alameda County as a whole.

Three generations of Gordon’s family have asthma. And Kidd talks about his neighbor’s daughter, whose breathing is fine when she stays with her mother in San Leandro, a city to the south of Oakland. But when she’s in West Oakland, she has to use a special device to help her breathe.

Margaret Gordon Encore.org

“It’s a widespread problem,” said Kidd, who doesn’t experience breathing issues. “All you can do is sympathize.”

Air pollution-related deaths from heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer are higher in West Oakland than in both the city and county. A white child growing up in the Oakland Hills, living on its winding streets overlooking the Bay, can expect to live more than 12 years longer than a black child born in West Oakland, part of the city’s “flatlands.”

“West Oakland wasn’t a place that people were standing in line to live,” says a nearly 100-year-old member of the community advisory group who has lived in the area for more than a half-century (and asked to remain anonymous). She attributes a lot of the health problems in West Oakland to activity at the army base.

But it was just the beginning. In 1957, freeway construction obliterated whole blocks and physically divided the area. Over the next two decades, a giant post office distribution center and an elevated Bay Area Rapid Transit station wiped out more homes and businesses, including many along historic 7th Street.

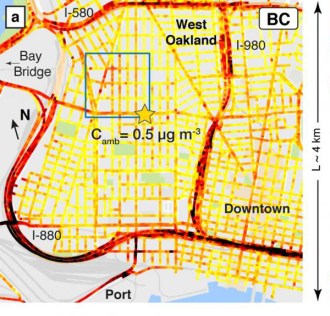

A study mapped the prevalence of black carbon in the air around the Port of Oakland. The highest concentrations, denoted in black, are at the interface between the port and the community of West Oakland. American Chemical Society

Today, while the shells of former warehouses have become art collectives, heavy industries like metal recycler Custom Alloy Scrap Sales, which Beveridge says supplies high-end car manufacturer Tesla, operate catty-corner from homes. And the port keeps hauling in cargo — 2.37 million 20-foot containers in 2016 — and shuttling trucks through West Oakland’s neighborhoods and onto the freeways.

The proximity of industry to homes naturally has its hazards: A study released in June, which used Google Street View cars to monitor air pollution for a full year, identified hotspots of black carbon throughout West Oakland’s neighborhoods. Black carbon is a tiny molecule found in soot, and a major contributor to climate change. In maps from the study, crimson lines denoting high black carbon levels follow the border that the port shares with adjacent communities.

Even after the closing of the army base nearly two decades ago, the port has continued to shuttle big money through West Oakland. But little gets reinvested in the local economy, says Beveridge. Truckers may stop at a repair shop or a convenience store, but residents say the traffic makes it difficult for local businesses to thrive.

“It’s the economic engine of the region,” Beveridge says. “It’s just not the economic engine for West Oakland.”

Before it closed, the army base — which at one point employed 7,000 people — provided plenty of jobs for locals. The city has estimated its redevelopment project would bring thousands of new opportunities to an area that desperately needs economic investment.

But Beveridge, Gordon, and other residents worry that the promise of jobs is intended to assuage the community’s environmental opposition. (Positions are not guaranteed to go to West Oakland residents though the city has a goal of hiring half employees from Oakland.) The city, the Environmental Indicators Project team asserts, refuses to adequately invest in a comprehensive analysis of the increased pollution from truck traffic and industry — or develop a plan for how to reduce emissions.

“I’ve seen the community used over and over again to get what other people want,” says the anonymous community advisory member, who is in her 90s. “Most other people have been winners. We’ve been losers.”

Other community members seem reluctantly supportive of any investment in West Oakland, even if it centers on industry.

Steve Lowe, a 77-year-old property developer and member of the community advisory group, says he’s “more or less” happy with the army base plan. But he, too, recognizes the environmental challenges facing the area — and supports calls for more air-quality monitoring and pollution mitigation. It’s not the first time the city has ignored input from West Oakland residents, he adds.

“Little by little,” Lowe says, “the ideas that we wanted to see happen were compressed, or eventually cut out.”

Oakland says it will use some federal funds for air-quality monitoring and environmental remediation. The last environmental review of the project, however, occurred before the city settled on logistics operations for its section of the site. Warehouses, like ports, attract a whole lot of vehicle traffic.

The mayor’s office did not comment before this piece was set to publish. But Mike Zampa, a spokesman for the Port of Oakland, says that over the years, it has upgraded to newer, cleaner trucks and reduced vehicle-idling time, so its operations emit less. Some residents also mentioned improvement in recent years.

“These folks are our neighbors,” he says. “We breathe the same air they do.”

Apart from cleaner air, residents simply want to see some response to the public health concerns they’ve lodged over the years. The civil rights complaint asks the U.S. Department of Transportation and the Environmental Protection Agency to investigate potential discrimination. But under the Trump administration, the federal government’s already dismal civil rights-investigation record is unlikely to improve.

Still, Earthjustice and the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project say they’re hopeful the complaint will jolt the city and port into taking their concerns more seriously. (Update: The day we published this story, the Department of Transportation and EPA informed the city and the port that they had opened an investigation into whether the approval process for the army base development was discriminatory.)

Brian Beveridge stands at Middle Harbor Shoreline Park Grist / Emma Foehringer Merchant

On a sunny Friday in June, Beveridge drives me down to the port in his white Ford pickup truck. “Usually there’s trucks in both lanes and in four directions,” he says above a classical symphony on the radio, as we turn towards the ocean.

A few minutes later, we stop at 38-acre Middle Harbor Shoreline Park, a slice of picturesque land sandwiched between port terminals where cranes stack royal blue, mustard, and rust-colored corrugated containers. The port built the park as part of its “Vision 2000” initiative, during an earlier expansion of operations. It opened in 2004.

“As beautiful as it is,” Beveridge says, standing in the grass and looking across the water to San Francisco, “it couldn’t be more surrounded by the port.”