This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

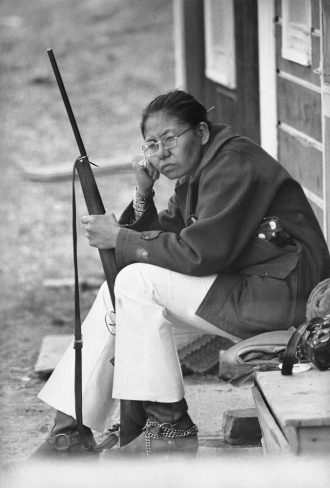

Regina Brave remembers the moment the first viral picture of her was taken. It was 1973, and 32-year-old Brave had taken up arms in a standoff between federal marshals and militant indigenous activists in Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Brave had been assigned to guard a bunker on the front lines and was holding a rifle when a reporter leaped from a car to snap her photo. She remembers thinking that an image of an armed woman would never make the papers — “It was a man’s world,” she says — but the bespectacled Brave, in a peacoat with hair pulled back, was on front pages across the country the following Sunday.

Brave had grown up on Pine Ridge, where the standoff emerged from a challenge to the tribal chair, whose alleged offenses included scheming to accept federal money for Paha Sapa, also known as the Black Hills. Brave’s great-grandfather Ohitika had helped negotiate the 1868 treaty preserving Lakota stewardship of the hills, but after white settlers found gold there, the lands were wrested away. Ohitika fought alongside his son, Brave’s grandfather, in an unsuccessful battle to save the Black Hills. Half a century later, the U.S. government agreed to pay $17.5 million in belated compensation.

Traditional Lakota of Brave’s generation believed that the chair’s bid to accept a settlement was sacrilege, and pressed their leaders not to accept the money, despite the tribe’s financial destitution. The 71-day Wounded Knee occupation ended with two natives dead and one federal marshal paralyzed. The chair remained in power for another three years, but the money remained untouched; no tribal council has yet accepted it, demanding instead, under the rallying cry “The Black Hills are not for sale,” that the land be returned. (The fund is now worth more than $1 billion.) The incident at Wounded Knee — on the same site where the U.S. Army massacred several hundred mostly unarmed Lakota nearly a century earlier — helped launch the American Indian Movement, and Brave’s career as a native rights activist.

Regina Brave sits with her rifle at ready on steps of building in Wounded Knee, South Dakota, 1973. AP Photo / Jim Mone

Now 79, Brave lives in a one-story house in a small town on Pine Ridge. Out front she parks the blue 2008 Grand Caravan she bought with her prize money from the ACLU’s highest honor, the Roger N. Baldwin Medal of Liberty, which she received in recognition of her leadership during the Standing Rock protest. After camping through a brutal winter, Brave was one of the last people arrested in the demonstration against the Dakota Access pipeline when police cleared their camp in early 2017. A photo of “Grandma Regina,” bundled in a blanket and wearing bright pink gloves, being led away by two police officers, was shared online as a symbol of indigenous resistance.

Today, Brave and other Lakota elders are staring down yet another encroachment on their historic lands: a 10,600-acre uranium mine proposed to be built in the Black Hills. The Dewey-Burdock mine would suck up as much as 8,500 gallons of groundwater per minute from the Inyan Kara aquifer to extract as much as 10 million pounds of ore in total. Lakota say the project violates both the 1868 U.S.-Lakota treaty and federal environmental laws by failing to take into account the sacred nature of the site. If the mine is built, they say, burial grounds would be destroyed and the region’s waters permanently tainted.

A legal win for the Lakota would represent an unprecedented victory for a tribe over corporations such as Powertech, the Canadian-owned firm behind Dewey-Burdock, that have plundered the resource-rich hills. And it could set precedents forcing federal regulators to protect indigenous sites and take tribes’ claims more seriously. The fight puts the Lakota on a collision course with the Trump administration, which has close ties to energy companies and is doubling down on nuclear power while fast-tracking new permits and slashing environmental protections — even using the coronavirus pandemic as an excuse to further roll back regulations. All of this makes Black Hills mineral deposits more attractive than they’ve been in decades.

For Brave, the Dewey-Burdock mine is just the latest battle in a long war to stop settlers’ affronts to Lakota lands and sovereignty. “They’re taking so much from [the earth] and not giving anything back,” Brave tells me, a hand-rolled cigarette dangling from her fingers. “I’m thinking we should say to them, ‘Get the hell off. Your rent is over.’”

The Lakota call Paha Sapa “the heart of everything that is.” Tribal origin stories say there was a Great Race between all the two-legged and four-legged creatures to determine who would eat whom. In one telling, the animals raced around the cedar-covered hills, and the magpie narrowly defeated the buffalo, establishing not only the dominance of the two-leggeds, but their responsibility to care for all living beings. Another tale says the Lakota emerged from a cave in the Black Hills following catastrophic floods. Lakota spiritual practices still center on the region.

Their people belong to a confederacy of tribes called Oceti Sakowin, the Seven Council Fires. Historically, the alliance’s range spanned parts of what’s now Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. Today, most of the 20,000 residents of the Pine Ridge Reservation, in the southwest corner of South Dakota, hail from the Oglala band of Lakota and are represented by the Oglala Sioux Tribe. (“Sioux” is an old French misnomer for Oceti Sakowin.)

When white frontiersmen blazed through these lands in the 1860s, an Oglala chief named Red Cloud led a war against the United States. The ensuing 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie created a Great Sioux Reservation that encompassed large swaths of the region, including the Black Hills, as the Lakota’s “permanent home.” Yet the deal was quickly broken. In 1874, “Indian killer” General George Armstrong Custer led an expedition that found gold in the Black Hills. Thousands of white settlers invaded the reservation in violation of the treaty, while also eyeing the hills’ timber and planning a new railroad through Lakota hunting grounds.

By then, many Lakota depended on government rations because the army, working with settlers, had virtually exterminated their primary food source, the buffalo. Fighting between Lakota holdouts and the Army culminated when Congress attached a “sell or starve” rider to the Indian Appropriations Act of 1876, cutting off rations to the Lakota until they agreed to cede the hills. By 1890, the Great Sioux Reservation, which had once covered about half of South Dakota, was fractured into six parcels constituting less than one-third of the area that many Lakota still consider their rightful “treaty territory.” The United States had seized the Black Hills.

When the gold rush petered out, mining companies pivoted to silver, tungsten, iron, and limestone. In 1951, uranium was discovered. Within 20 years, there were more than 150 uranium mines centered on a small boomtown called Edgemont, in Paha Sapa’s southern foothills, where the Oglala once made their winter camp.

On my drive west from the pale slopes of Pine Ridge, the Black Hills, whose crowning thickets of juniper and pine give the range its dark appearance, look like the ramparts of another world. The southern foothills are rocky and quiet, but just north, bikers and families in RVs clog the highways to visit abandoned gold mines, old-timey saloons, and the main attraction, Mount Rushmore, which was carved into a sacred mountain known to the Lakota as the Six Grandfathers. “We call it the Shrine of Hypocrisy,” says Tonia Stands, an Oglala Lakota who has been one of Pine Ridge’s most persistent voices against uranium mining.

KEREM YUCEL / AFP via Getty Images

For decades, Lakota activists have raised alarms about the risks uranium mining poses to their communities. In 1962, radioactive material seeped from a broken dam into the Cheyenne River, upstream from Pine Ridge. Mining ceased in 1973, but the reservation continues to grapple with epidemic levels of birth defects, cancer, and kidney disease. Today, Pine Ridge has the lowest life expectancy of any U.S. county. The rampant health issues help explain why reservation leaders took swift action to stem the spread of coronavirus before they even confirmed their first case.

While no evidence has definitively linked their health problems to mining, many Lakota believe that uranium contamination is partly to blame, and they point to the Environmental Protection Agency’s settlements in response to the effects of mining in the Navajo Nation, which acknowledged links between high levels of uranium in soil and drinking water and cancer, kidney disease, and reproductive issues on the reservation.

In 2012, Stands and other Lakota women supported efforts to lobby the EPA to clean up the open pits around Edgemont. As the agency began to investigate the source of the contamination, non-native landowners barred agents from taking samples at defunct mining sites. The EPA had to rely on sampling data that Powertech collected while preparing its application to open the Dewey-Burdock mine. Based on that data, regulators concluded in 2016 that the region’s water naturally contained high levels of uranium and did not require cleanup.

Stands wears her hair in a single black braid reaching all the way down her back. Her grandmother was a “uranium fighter,” as was her late uncle Wilmer Mesteth, who helped found the Oglalas’ Tribal Historic Preservation Office. In 2010, three years after Powertech began the process of licensing Dewey-Burdock, Mesteth and the tribe filed a petition with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), which oversees uranium mine permitting, to stop construction. They argued that the project was moving forward in violation of their sovereign will as well as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the landmark 1970 law requiring federal agencies to document the impacts of all projects they build or license. According to the tribe and local geologists, Powertech failed to collect enough data to prove that the mine would not contaminate groundwater, and did not adequately assess how it would affect sites of cultural importance.

In 2015, a panel that adjudicates claims against the NRC dismissed the environmental arguments against the mine and allowed its license to continue. Yet tribal members claimed a battle victory in the “paper war” because the board ruled that more tribal input on cultural sites would be necessary to satisfy NEPA.

Since Mesteth’s tenure, the Tribal Historic Preservation Office has been occupied by a revolving cast of officials who have not always sustained resistance to the mine. So Brave and Stands convened a group of women called Magpie Buffalo Organizing to keep the fight alive. “We are the women that have learned, and we are the leaders,” Stands says. “When we get depleted, when there’s nothing else to give … it’s just like lightning, or like magic. We’re going to strike something back.”

Adding a layer of oddity to the whole situation, Powertech is so far a mining company only on paper. It has never produced an ounce of ore and can only keep litigating as long as investors remain convinced that footing its bills will eventually pay off. Powertech anticipates the mine will net about $150 million, yet it says it’s already sunk $10 million into the NRC license, not including litigation or staffing costs. Its parent company, Azarga Uranium, trades as an underregulated penny stock; investment firm Haywood Securities rates its risk factor as “very high.”

For years, it seemed like the Lakota could drag out the case long enough to make Powertech’s prospects no longer worth the fight. The price of domestic uranium was on a steady decline: The federal government already had vast stockpiles, and nuclear energy producers could import it more cheaply from places like Australia and Canada. By the end of 2018, all but five U.S. uranium mines had been shut down or suspended. Yet today, Powertech is just one of several companies applying to open new mines, anticipating that an administration bent on deregulation, and the appeal of nuclear power as a climate-friendly energy source, could increase profitability.

In July 2019, after lobbying from uranium producers, President Donald Trump convened a Nuclear Fuel Working Group to devise policies that could throw a lifeline to the struggling industry. Released in April, the group’s report won applause from Powertech’s parent company by recommending renewed federal investment in uranium. Though many experts say the U.S. already has more of the mineral than it can use, Trump’s proposed 2021 budget would allocate $150 million to stock a new reserve with domestically mined uranium. The share prices of U.S. mining companies jumped after the report’s release, while factors related to COVID-19 caused the global price of uranium to surge throughout March and April.

Trump has found other ways to boost mining and energy interests in and around reservations and sacred native sites. During his first week in office, he fast-tracked approval of permits for the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines, which are opposed by members of hundreds of tribes. He later ordered federal agencies to prioritize projects that limit domestic reliance on foreign sources of 35 “critical minerals,” including tin, lithium, and uranium. And he has opened the floodgates for oil, gas, and mining claims on millions of acres by removing protections for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and Bears Ears National Monument, which is also sacred to native people, while his EPA has nixed Obama-era rules requiring mining companies to clean up their sites and restore contaminated groundwater.

He’s also waging war on the cornerstone of environmental law: NEPA. A 2017 executive order establishing a One Federal Decision process for infrastructure projects, which would limit the redundancy of multiple agencies reviewing the same project, has been praised for boosting efficiency, but more ominously would accelerate the timeline for environmental impact analyses by directing agencies to complete reviews within two years instead of about four and a half. The Council on Environmental Quality, which oversees NEPA compliance, is considering formal limits on the length and scope of reports.

Under Trump, the Department of Interior has limited its NEPA reviews to one year and 150 pages, which may be long for a term paper but not for these highly technical and consequential reports. A study on drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which Alaska natives have fought against for decades, was criticized by government scientists for omitting possible harms to polar bear habitats and indigenous communities. Trump intends to open the region for drilling anyway. A similarly hurried impact assessment has greenlighted the Pebble Mine, a project previously considered untenable due to the harm it poses to salmon spawning in Alaska’s Bristol Bay. In the Black Hills, three companies are now working with the Forest Service to review prospects for gold mining. As Claudia Nissley, a Colorado-based corporate NEPA consultant, puts it, Trump’s executive orders “have pushed us back to the old days.”

Last August, Brave and a dozen tribal members gathered in a hotel ballroom in Rapid City for the latest hearing in their case. The NRC judges, three white men, sat at one end of the room, a photo of Mount Rushmore at their backs. Having lost their claims about environmental harm, the tribe’s lawyers are still trying to convince regulators that the uranium mine would irreparably damage Lakota burial grounds, places of ceremony, and other sacred sites.

The problem is that while NEPA technically requires agencies to consider a project’s potential impact on cultural heritage sites, such reviews rarely take place. (The same is true of environmental impact reviews. According to the Council on Environmental Quality, less than 6 percent of federal projects receive any environmental assessment.)

“There’s a lot of political pressure for these projects to go forward,” says Kelly Morgan, a NEPA consultant who is Lakota and testified at the hearing. Federal agencies “are falling back on ‘We’ve met the minimum requirement.’ But have they really?”

Before it first submitted its proposal, Powertech commissioned its own study. In it, archaeologists remarked on the “sheer volume” and “high density” of cultural sites in the hills, including possible human burials. After the Lakota filed their NEPA complaint, the NRC invited them and other tribes to help with a new survey of the proposed project area. Mark Hollenbeck, Powertech’s Dewey-Burdock project manager, says the company “surpassed” NEPA requirements by offering to pay tribes for participating in the survey. The Lakota declined to participate, and they say they won’t take part until the NRC engages them as a sovereign nation with an approach that’s more culturally sensitive.

Nissley, who teaches seminars on NEPA at the National Preservation Institute, a professional training organization, says she uses Dewey-Burdock as a case study of “what not to do.” In her view, the NRC waited too long to involve tribes in the project’s review. “The tribes have not been shy about saying what a sacred area this is,” she adds. “Any tourist guide would say this. But had the Oglala Sioux Tribe not intervened, everything would have just kept moving.”

Even when cultural reviews do happen, they can be skimpy and ineffective. In her decade of working in this field, Morgan has seen agencies and companies assign the task to junior staff who lack the necessary archaeological background or cultural training. And a finding that sacred sites would be compromised rarely results in a project’s rejection. At best, a tribe or community might win “mitigation,” slightly amending the project to bypass a heritage site, even if the project restricts access to that site or renders it unrecognizable.

More often, the NRC defers to the company’s interests, as happened in the case of Dewey-Burdock: Though it agreed that the tribe was right to ask for a better study, the agency spent years defending Powertech’s claim that it should not have to fund the Lakota’s request.

Energy and mining companies are treated “like clients instead of regulated entities,” says Jeff Parsons, one of the tribe’s lawyers. The NRC and its permittees “are in absolute lockstep, opposed to citizen and tribal involvement” in a process designed to protect exactly that.

It’s not just the NRC. After the agency rejected the tribe’s environmental arguments, Parsons filed an appeal with the D.C. Circuit Court. In 2018, the court agreed that the NRC violated the law by licensing Dewey-Burdock even after its own review panel found “significant deficiency” in the cultural review. But the court declined to vacate the license, citing Powertech’s lament that its stock price “would plummet.”

In Morgan’s view, settler heritage sites are commonly protected while tribes must fight “tooth and nail every step of the way” to win minor concessions as their sites are destroyed “at an astounding rate.” During the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline, for example, multiple burial grounds were bulldozed.

“We’re not talking about Mesopotamia. We’re talking about living, breathing nations of people,” says Morgan, who has close-cropped hair and wore a masculine vest and tie to the hearing. “Their medicine people still make the trek to these areas every year. The cosmology is intact, the cultural lifeways are intact, and we practice our ceremonies by going to specific locales within that concentric area” where Powertech wants to build a mine.

At the August hearing, the NRC argued that it had gathered as much information as it could without funding an “exorbitant” survey, while Powertech’s counsel decried the many years already spent, adding, “We fully support [the] NRC staff’s position.”

Sounding exasperated,Morgan jumped in. “It’s our job to save as many of these sites as possible,” she said, “because they are finite. They are a map, and they tell a story. It’s a very sensitive personal thing to us as Lakota people.”

After the hearing, Brave and Stands met in a nearby park with the other Lakota who’d driven from Pine Ridge. Sharing their huge pot of stew with homeless people there, most of the group concurred that their case looked strong. But the judges were unmoved: In December, they ruled that the NRC had satisfied NEPA’s requirement to take a “hard look” simply by making a “reasonable effort,” resolving the last objection to the license. “The system is set up to fail our people,” Stands says.

When Brave was just a kid, her grandfather made her memorize the text of the violated 1868 treaty. That came in handy when tribes and the Army Corps of Engineers, which issues permits for projects that cross waterways, were fighting over the Dakota Access pipeline. “When we were at Standing Rock, they said, ‘This is Army Corps of Engineers land.’ And I said, ‘Bullshit. This is treaty territory. The Army Corps of Engineers is not a country and cannot make a treaty with us. We’re sovereign.’”

For the Lakota, sovereignty means the right to determine for themselves what happens on their lands. As the COVID-19 threat grew, the Oglala Sioux and other Lakota tribes exercised sovereignty by closing their borders to non-residents. Statements, memos, and executive orders from presidents Reagan through Obama proclaimed that Washington would approach indigenous tribes on a “government-to-government” basis, directing federal agencies to engage in “regular and meaningful consultation and collaboration” with tribes regarding policies and projects that affect them.

Yet in 2017, after 60 tribes filed federal complaints about the Dakota Access pipeline, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, an independent government body, surveyed many tribes that decried the consultation process as hollow. “Many tribal commenters felt that unless federal agencies are willing to reject project proposals based on tribal objections, tribal input is essentially meaningless,” its report said.

A shift from merely consulting tribes to making projects contingent on tribes’ involvement and input, a central tenet of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, would represent a monumental change. Under such a policy, the Keystone XL pipeline would likely be blocked by the tribes whose lands it would cross. In 2019, the state of Washington became the first to require the “free, prior, and informed consent” of recognized tribes on any project that “directly and tangibly affects” their people, lands, or sacred sites. In both federal and state supreme courts, tribes are beginning to win more rulings in favor of their long-forgotten treaty rights.

The Oglala Sioux’s drawn-out legal challenge to Dewey-Burdock is pushing regulators to acknowledge that federal laws require the tribe’s meaningful consultation in the review of all projects in the Black Hills. The tribe has appealed the NRC board’s ruling, and Parsons, the Oglala Sioux’s lawyer, suspects that if the agency finally involves tribal members in a cultural survey, it’ll find enough sacred sites and burials to make a uranium mine much less likely. “If they do the surveys and still want to mine, then at least we can fight about whether it’s a proper place,” he says. “Right now we’re fighting just to get the data.”

In October, Brave spoke at Magpie Buffalo Organizing’s inaugural “No Uranium in Treaty Territory” summit, which offered a crash course on tribal sovereignty. The activists are closely tracking the various Keystone XL permits, which the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is challenging in court as a treaty violation. As the threat of both uranium and gold mining looms, there’s talk of occupying land in the Black Hills, as the American Indian Movement did in 1981.

For most of her life, Brave hadn’t understood why her grandfather made her memorize the treaty. It didn’t stop the Black Hills gold rush in the 19th century or the uranium boom in the 20th. Nobody knows how many sacred sites were destroyed — but now there’s a chance to protect those that remain.

Brave’s grandfather said the Lakota would one day need to return to the caves in the Black Hills where they rode out the last great flood. That’s “the reason that we really try to treat it as a sacred area,” she says. “We have to go back to it when the time comes.”

“I always imagine a rope with all these different knowledges on the string that brings it down through the generations. And I see ’em as broken — a lot of strings are broken coming down,” Brave says. “They fenced us in as prisoners of war, but now we’re talking treaty. I’d like to see how they’ll handle that.”