More than 150 years ago, a renowned physician named John Snow walked the gritty streets of London’s working-class Golden Square neighborhood, not far from his office in the city’s Soho district, knocking on the doors of residents felled by the cholera epidemic. Why Soho was so hard-hit had vexed London’s health officials, but Snow, known today as the “founding father of modern epidemiology,” used maps, public records, and his sleuthing skills to find the source of that devastating outbreak: contaminated water from a public water well pump on Broad Street. To find answers, he became an intrepid, Victorian-era medical detective who went door-to-door collecting information on residents’ water sources to determine how the deadly disease spread. (Steven Johnson recounts these steps in The Ghost Map, his book on the 1854 epidemic.)

It was no accident that Snow, the son of a coal yard laborer, was the person who made this breakthrough. Though he had reached the heights of British society as Queen Victoria’s anesthesiologist, as well as a respected surgeon and brilliant inventor, at his core he was a researcher who built bridges across disciplines and classes, notes Johnson. He was as comfortable in the Queen’s palace as he was on the bleak streets of Golden Square. Snow brought not just his insights as a working physician, but also the social connections he had with residents, his roots with the working poor, and his local knowledge of the streets that he canvassed. (The epicenter of the Golden Square outbreak was a mere six blocks from his home.) By examining the patterns of how people lived and died at the neighborhood level, Snow found solutions that were grounded in science, rather than superstitious moralizing.

“Nowhere in Snow’s writings on disease does one ever encounter the idea of a moral component to illness,” writes Johnson. “Equally absent is the premise that the poor are somehow more vulnerable to disease thanks to some defect in their inner constitution…. The poor were dying in disproportionate numbers not because they suffered from moral failings. They were dying because they were being poisoned.”

Today, as COVID-19 continues its deadly march across the world, the U.S. is emerging from a politically divisive election that gave few indications that the country can find the common ground needed to bridge its social differences in service of a common good. We’re a country at a crossroads, facing a reckoning on the heels of a nationwide movement for racial justice that has left much unresolved. Our immediate focus is rightfully on finding ways to effectively slow the spread of COVID-19, which has been disproportionately suffered by communities of color and the poor. Preventing such devastation in the future will require that we address long-standing economic and environmental inequalities facing these same communities. The larger question is whether we can, at last, bridge a geographic divide created by the legacy of segregation, which has resulted in our separate and unequal America.

Recent research by Jessica Trounstine, a professor of political science at the University of California, Merced, has found that the effects of segregation and local public policy decisions across the country have produced unequal access to basic city services and public works — a form of inequality that’s become embedded in the fabric of American cities. This inequality — where the haves and the have-nots are divided by street, by neighborhood, and by city, and where the poor and communities of color receive fewer and lower-quality public services — has in turn contributed to the racial political polarization of our country, according to Trounstine.

In her 2018 book Segregation By Design, Trounstine details how local public works in the early 1900s significantly reduced outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and typhoid fever. The infectious disease mortality rate dropped by 75 percent between 1900 and 1940, and part of that decline was due to the development of public water and sewer systems by local municipalities. These benefits were far from universal, however, and from the beginning low-income residents and communities of color received fewer of these types of services. Even when they did receive them, the services were of lower quality. “They were less likely to be connected to sewers, to have graded and paved streets, or to benefit from disease mitigation programs,” Trounstine writes.

These inequalities persist today, with some neighborhoods having access to clean water, ample green space with playgrounds, and functioning sewers, while others don’t. Segregation, both official and de facto, allowed for that unequal provision of public goods and services. Trounstine argues that local governments have deepened this divide by shaping residential geography through local land use policies, such as zoning laws. It’s what she calls “segregation by design.”

During the second half of the 20th century, as white flight left urban centers with a reduced tax base, those inequalities widened — and, with them, the politics of the advantaged and disadvantaged diverged, too. In advantaged places, Trounstine found that residents are politically conservative and vote at higher rates for Republican presidential candidates, favor lower taxes and limited spending, and see inequality as a result of individual failings. Ultimately, by regulating land use, planning, zoning, and redevelopment without taking into account the challenges faced by marginalized communities, local governments have deepened segregation along lines of race and class — a process that has benefited white property owners at the expense of people of color and the poor, Trounstine concludes.

The consequences of this divide have been far-reaching and long-lasting. Researchers have found that racial segregation influences a broad spectrum of factors that determine a person’s life outcome, leading to higher poverty rates, lower educational attainment, and higher rates of incarceration. Segregated neighborhoods become communities where this disadvantage compounds, leading to an entrenched inequality that is difficult to escape and is passed from each generation to the next, according to Harvard Professor Robert Sampson, who explores this in his book, Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Sampson concludes that this inequality can be broken through the type of structural intervention that governments are equipped to handle. History, however, has shown us that those with political power have failed to take action to eliminate these inequalities, leaving communities of color asking whether the American dream of equality for all will ever be within reach during their lifetimes.

Throughout his life, the writer James Baldwin questioned whether the United States would finally confront the hypocrisy of a democracy that was founded on principles of equality, but had in fact created a system that valued white lives above all other lives. At the height of the civil rights movement in the early 1960s, Baldwin cautioned his nephew of the perils ahead for him in a country that placed him in a ghetto, intending for him to “perish.” In his essay “A Letter to My Nephew,” which became part of his 1963 book The Fire Next Time, Baldwin decried the conditions into which his nephew was born: “conditions not far removed from those described for us by Charles Dickens in the London of more than a hundred years ago.” The 1960s was an era of violence and resistance to the calls for change — a dark moment in our history, as freedom fighters lost their lives in this battle for civil rights and equality. “I know how black it looks today for you,” Baldwin wrote his nephew. Yet despite all of his trepidations, Baldwin held out hope that we collectively could “make America what America must become.”

James Baldwin poses during a portrait session on September 23, 1985. Grist / Ulf Andersen / Getty Images

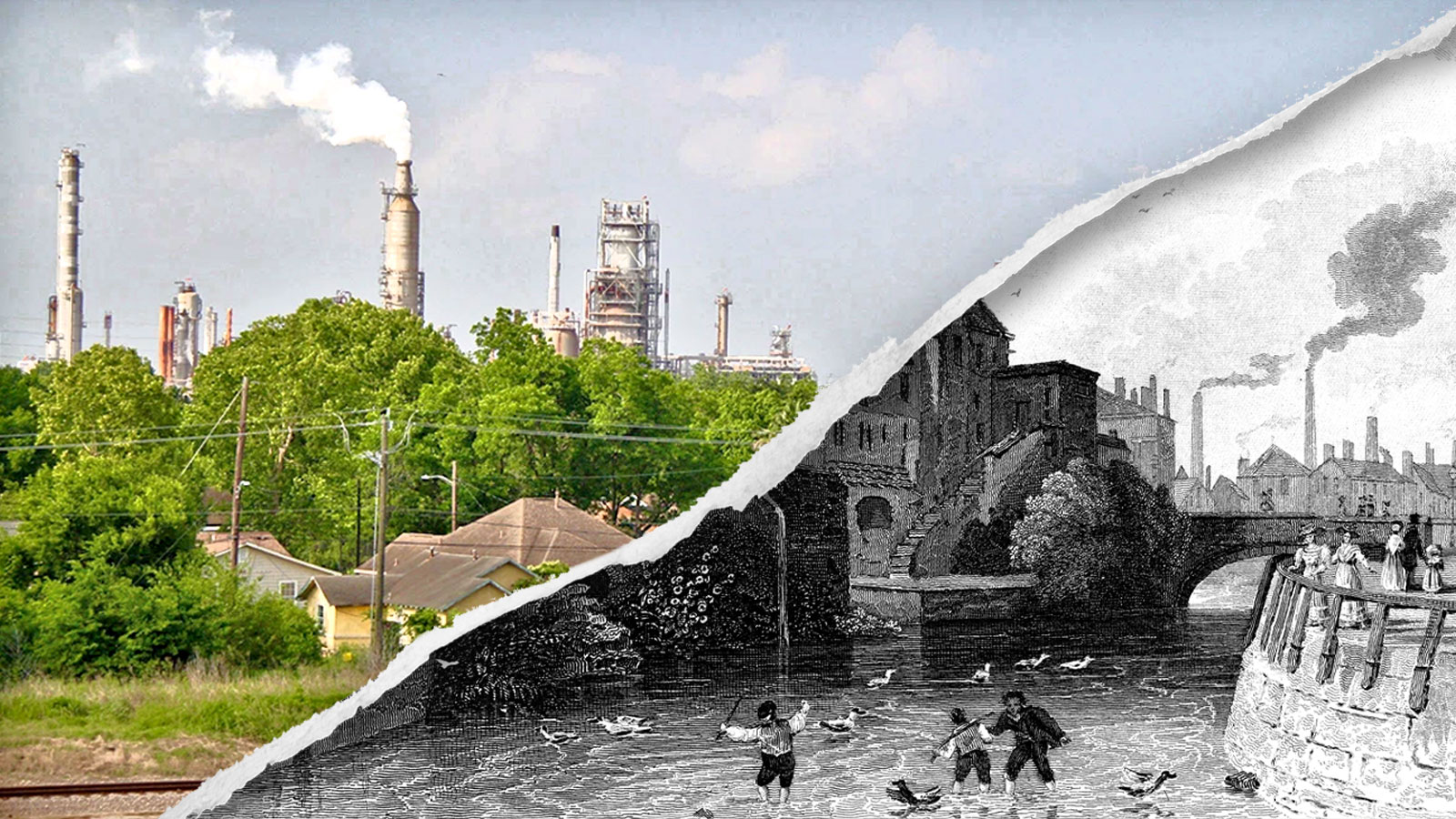

Time and again, we have been faced with those same choices Baldwin identified, but have failed to make the right choice. The U.S. is hardly alone in this regard. In 1843, Charles Dickens visited the industrial city of Manchester, England. Walking the streets he saw a polluted, poverty-stricken city that would later be dubbed the “chimney of the world” because of the coal-fired, smog-emitting factories that clouded its skies. The pollution was so thick that residents commonly suffered from rickets because the darkened skies prevented vitamin D-producing sunlight from piercing through, according to author Les Standiford. In his book The Man Who Invented Christmas Standiford explains how Dickens’ trips to Manchester informed his writing of A Christmas Carol.

At the time, Manchester’s laborers and their families lived in squalid districts with unpaved streets and without common sewers. Their poorly ventilated homes had dirt floors and lacked windows and doors. Part of what inspired Dickens to write A Christmas Carol was the sense of outrage he felt upon witnessing the destitution of the working class in Manchester and beyond. Dickens crossed social boundaries to bridge the divide in an unequal British society, and every holiday season we celebrate that spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood by recounting his tale of generosity and love toward others. Nevertheless, the disparities we allow to exist across America today tell a very different story about our society.

Nearly 200 years after Dickens walked the streets of Manchester, England, children living in another Manchester right here in the U.S. — this one a roughly six-square-mile working-class Latino enclave in east Houston, Texas — are so accustomed to looking up into the sky and seeing billowing grey smoke from the 19 nearby industrial facilities that they’ve come to describe them as “cloud-makers.” Despite research showing excessive levels of air pollution in Manchester, public officials have done little to hold polluters accountable.

“We have the proof here, but it’s like [elected officials] are blind. They don’t want to admit it,” said Juan Parras, the founder and executive director of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (t.e.j.a.s.), an organization that provides residents with the tools to protect themselves and the environment through legal action, community awareness and education, and stronger government policies and regulations. Despite a lack of government action, t.e.j.a.s. plans to continue to amplify the findings of academic and scientific researchers who have found, for example, that the cancer risk in Manchester and an adjoining neighborhood is 22 percent higher than it is in the overall Houston urban area. “We have all the proof, the research, yet nobody wants to follow up on the recommendations,” said Parras.

A Valero oil refinery in the Manchester neighborhood of Houston, Texas. LOREN ELLIOTT / AFP via Getty Images

Decades ago, environmental sociologist Robert Bullard’s groundbreaking research on the siting of landfills and polluting industries near communities of color in Houston led him to conclude that not only does a person’s zip code predict their health outcomes, but also that race is a more potent predictor than income of how pollution is distributed. Researchers have concluded that the best way to reduce these inequalities is by reducing residential segregation. One way to achieve this is by increasing political representation of the marginalized, the poor, and people of color. Trounstine found that, in urban areas where marginalized residents participated in politics and asserted power by voting or holding elected office, they received more public services and benefits from municipal governments,” “Where and when people of color had political voice, segregation and inequality were lessened,” she writes in Segregation By Design.

By reducing segregation, we can likewise reduce political polarization. Trounstine has found that the people we regularly interact with influence who we vote for, our views on policies, our political affiliations, and how we process information. “Simply put, segregation affects our social networks. And segregation affects tax rates, wealth acquisition, and educational opportunities, which in turn affects political preferences,” she writes. “Increasingly, people feel hostile toward those on the other side of the political aisle.”

Trounstine suggests that state governments are best-equipped to tackle this problem, given the authority that constitutions provide individual states to address public issues like preserving the natural environment, providing health care, regulating water, and caring for society’s most frail residents. “What is clear is that if we do nothing about this design, politics will continue to polarize, and inequality in wealth, education, safety and well-being will continue to worsen,” she writes. “Much is at stake.”

Recently updated maps from the 19th century have shown how pockets of poverty in Victorian-era London have persisted in contemporary London. Is there something to be gleaned from the way John Snow investigated the cholera epidemic of 1854? Johnson, the author of The Ghost Map, points out that the problems Victorian-era British residents faced are still relevant more than a century later. They too wrestled with the question of how a society could industrialize in a humane way. Snow’s insights came from a confluence of factors that together led to his breakthrough: his working-class upbringing, his dogged pursuit for answers, and his time spent questioning residents on the streets of his neighborhood. By doing this, he was able to see beyond the biases of his society and connect the dots between the plight of cholera patients and the broader social structure of society.

As we face our own 21st century Manchesters in the U.S., will we see beyond our own biases and dismantle the practices that have placed race and racism at the center of local policies? It’s clear that residents in communities with the least access to clean water, healthy air, and uncontaminated soil are the most susceptible to the ravages of COVID-19. Rebuilding a just America means redesigning cities and towns, cleaning up contaminated and polluted neighborhoods, and creating spaces where we can coexist, learn from each other, and discover solutions that will protect all lives from the ills that plague us, whether it’s coronavirus, environmental contamination, or poverty.

In an excerpt from his memoir, former President Barack Obama emphasizes the necessity of coming together to raise up the voices who will carry us forward and create a united America, one that fulfills its promise of equality and justice for all. “I’m convinced that the pandemic we’re currently living through is both a manifestation of and a mere interruption in the relentless march toward an interconnected world, one in which peoples and cultures can’t help but collide,” Obama writes. “In that world — of global supply chains, instantaneous capital transfers, social media, transnational terrorist networks, climate change, mass migration, and ever-increasing complexity — we will learn to live together, cooperate with one another, and recognize the dignity of others, or we will perish.”

In this world of instant connections and constant communication, perhaps we’ve overlooked the one element that can help us transform our divided America: understanding. The most dangerous disease is the one that robs us of the ability to empathize with others, to understand their situation and find a way to help, no matter what their station in life. That was the gift that John Snow carried with him every time he stepped out of his London home to help his patients. Sometimes, the deepest wounds require old-fashioned medicine, the kind that doesn’t come in a bottle — the kind that helps one see the world with compassion.