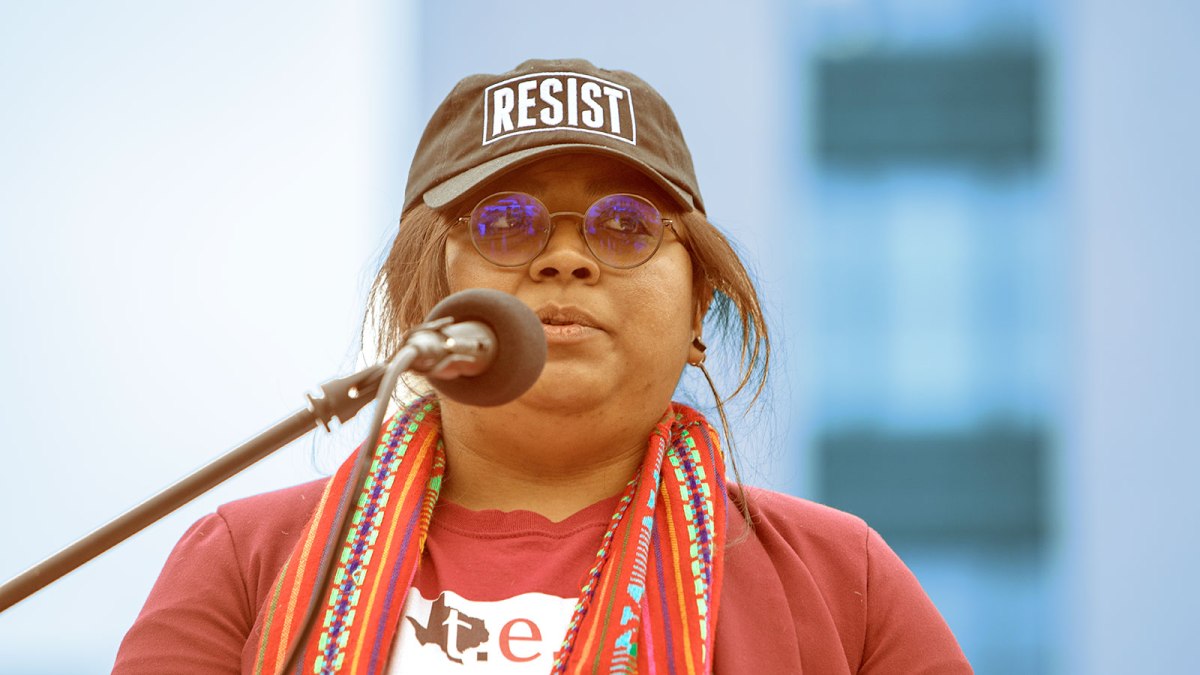

Yvette Arellano has fought for years against the oil, gas, and petrochemical infrastructure that has inundated her home state of Texas. For her, the fight is personal. Two months ago, she was diagnosed with a reproductive health condition, joining the many Texans — particularly children and people of color — that have experienced cancer, respiratory disease, and developmental problems that they believe are associated with fossil fuel industry pollution.

Arellano, a political analyst for Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services, has led several campaigns over the years to fight the industry’s expansion in the Lone Star State — and she credits a significant amount of her success to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a law that requires federal agencies to consider the environmental impacts of proposed federal actions, including the construction of major highways, airports, and pipelines. Passed in 1969, NEPA allowed Arellano and many other community advocates in oil-friendly states like Texas to participate in the decision-making process of major projects.

But earlier this year, the Trump administration proposed an overhaul of key elements in the 50-year-old law — elements that vulnerable communities have long utilized to protect their health and the environment. In particular, the proposed revision would limit requests for community input prior to decision-making by federal agencies. This Tuesday is the final day for members of the public to submit comments on the rollback.

Last month, the White House Council on Environmental Quality held two public hearings to gather feedback on the administration’s proposed revision of NEPA. Though Arellano was unable to secure a spot in the hearings themselves —an Eventbrite link that the government required for RSVPs quickly reached capacity — she still traveled thousands of miles to the hearing locations in Denver, Colorado, and Washington, D.C., to tell her community’s stories.

Yvette Arellano speaks at a rally in Washington D.C. against the Trump administration’s proposed rollback of the National Environmental Policy Act. Grist / Moving Forward Network / Antonio Hernandez

“Why is it that CEQ just has the hearing here [in Washington] and the hearing in Denver? Why not have a hearing in Texas or [California’s] Inland Empire, where this process also matters?” Arellano told Grist outside the hearing in February. “I don’t know how much it matters to folks who are simply striking all of this with a simple penswipe.”

Others who couldn’t enter the Interior Department building where the hearing was held rallied outside in the rain, arguing against the proposed rollbacks through a loudspeaker as government employees walked by on their lunch breaks. Inside the building, people lined up to grab their badges and enter the large hearing room. From construction workers to university professors, many testified against Trump’s proposed rollback before a panel of White House officials who scribbled notes — and only occasionally looked up at the stakeholders standing at the podium below.

Advocates have critiqued the proposed revision for narrowing the scope of the review process, limiting consideration of project alternatives, and no longer requiring an evaluation of any given project’s impact on climate change. These critics argue that new exemptions for “smaller projects” and added requirements that public comments be “specific” and “timely” are meant to fast-track projects at the expense of community concerns.

Low-income communities of color across the country have long invoked NEPA to fight major projects that would damage the environment, threaten public health, and occupy indigenous lands. Recently, activists were able to leverage NEPA to throw up significant roadblocks to the construction of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline.

A truck drives past a Keystone pipeline pumping station near Milford, Nebraska. Grist / AP Photo / Nati Harnik

An intergenerational fight

Taylor Thomas, who was raised two blocks away from the 710 freeway in Long Beach, was playing outside her home when she had her first asthma attack at 7 years old. For a while, she had to use an in-home nebulizer machine to control her breathing. In Southern California, she’s hardly alone: Thomas joined the 15 percent of children in Long Beach who had also been diagnosed with asthma, which many trace back to the dirty air they breathe.

The 710 freeway, which stretches from Long Beach to East Los Angeles, has been dubbed the “diesel death zone” because of the massive amount of diesel emitted from freight trucks, ships, trains, and industrial facilities that blanket the busy corridor, which culminates in one of the country’s busiest ports. For over a decade, Los Angeles County leaders have pushed for a major project to expand the freeway, despite residents’ concerns about displacement and pollution. Thomas and others in the Long Beach area invoked NEPA in response and were able to force the consideration of various project alternatives that focused on sustainable architecture that could limit displacement, in lieu of the highway expansion.

“It’s been a multi-year fight, but it’s also been an intergenerational fight. It’s been a whole type of community fight,” Thomas, now 29 and a research and policy analyst for East Yards Communities for Environmental Justice, told Grist before she delivered her testimony at the D.C. hearing. “We’re part of a coalition made up of folks up and down the corridor, so NEPA has been like a bridge for us to be able to come together against this really big project.”

In the end, Los Angeles County transportation officials did an about-face and halted the 710 expansion project. Thomas’s victory might not have been possible if Trump’s revisions had been in effect at the time of her fight: The proposed rollback would limit the consideration of project alternatives, with stricter language stipulating that such alternatives must be “technically and economically feasible.”

50 years of NEPA

NEPA, signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1970, was the first significant piece of federal environmental legislation in U.S. history. It established the White House Council on Environmental Quality, made it a requirement for major federal projects to produce environmental impact statements and environmental assessments, and ultimately led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Environmental activists protest against the Trump administration’s proposed revisions to NEPA. Grist / AAron Ontiveroz / The Denver Post

NEPA regulations have not been extensively updated in over 40 years. The policy requires a thorough environmental review of a broad range of federal actions, such as federally-funded construction projects, plans to manage federal lands, and other corporate projects requiring federal approval for licenses and permits.

But in 2017, President Trump issued an executive order that included a two-year goal to complete environmental reviews for pending major infrastructure projects and an order to revamp NEPA requirements for future projects. The proposed revamp would make it easier for the government to consider public comments and objections “exhausted and forfeited.”

In addition, the rollback also proposes to establish a one-year limit for environmental assessments of projects and a two-year limit for environmental impact statements, which are more strict. As these statements and assessments have sometimes required four or more years to complete in the past, approvals seem likely to accelerate if the revisions go through. The proposed regulations have been celebrated by industries arguing that major infrastructure projects are subject to too many delays under the current rules.

Fostering climate denial

Coming out of the civil rights movement, Mildred McClain has long fought for justice in her hometown of Savannah, Georgia. But it wasn’t until a nearby nuclear facility began leaking radioactive chemicals into the Savannah River that she became immersed in the environmental movement.

Dr. Mildred McClain speaks at a rally against the Trump administration’s proposed revisions to NEPA. Grist / Moving Forward Network / Antonio Hernandez

McClain, now 70, has leveraged NEPA to rally her community and call for public hearings on controversial infrastructure projects. For decades, she spoke out against polluting industries and became known as an environmental justice pioneer. Most recently, she’s been working to push against a major project to expand the Port of Savannah, another of the country’s busiest seaports. Cargo ships are a significant source of global air pollution, and the expansion’s impact on increasing greenhouse gas emissions — and its contribution to climate change — was at the core of the opposition.

“Had it not been for NEPA, we would have totally been excluded from the discussion and the environmental assessment process, and we would not have been able to mobilize residents,” McClain told Grist. “We were able to get the voices of local neighborhoods, which we call the ‘environmental injustice communities.’”

McClain calls the predominantly black neighborhoods adjacent to the port environmental “injustice” communities because the fight is still ongoing. Last month, President Trump’s budget proposal included $93.6 million of funding to continue dredging Savannah’s harbor to allow bigger container vessels. This means McClain and the rest of the community have just a few more months to leverage NEPA before the revisions get finalized. (A finalized version of the revisions will be announced in the fall, before the 2020 presidential election.)

Through NEPA, McClain has argued against the expansion project by citing data about the long-term climate impacts of diesel emissions. NEPA currently requires federal agencies to examine and disclose a proposed action or project’s direct, indirect, and overall impacts on climate change, including its potential carbon footprint and contribution to global temperatures. However, Trump’s revision alters the definition of the “cumulative impacts” of a project — which includes climate change — and eliminates the terms “direct” and “indirect,” which could prevent the disclosure of this information to the public.

President Donald Trump proposes changes to the National Environmental Policy Act in January 2020. Grist / Drew Angerer / Getty Images

“If Trump gets back in, the will to change is not going to be there, and we’re going to be in a fight for our lives,” McClain said. “He has weakened things that we have fought for for the last 30 years.”

As climate change accelerates and the Trump administration continues to roll back environmental regulations, low-income communities of color will be the first to suffer the ramifications, Mcclain argues. The proposed NEPA revisions simply aggravate existing systemic burdens.

“People in environmental justice (or injustice) communities are overwhelmed by their everyday lives,” McClain said. “They are inundated with issue after issue, so to propose to roll back or eliminate a tool that is part of that democracy is just unacceptable.”

“In democracies,” she added, “people are supposed to have a voice.”