At the urging of one of the country’s main agricultural unions, farmworkers across the country walked out on their jobs in fields, vineyards, and orchards on Monday for 8 minutes and 46 seconds — the same amount of time George Floyd was choked under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. This protest was a part of a nationwide “Strike for Black Lives” in which a coalition of essential workers demanded justice for Black communities, including fair voting rights, health care, and sick leave for workers affected by COVID-19.

“Most farm workers, living and laboring in remote rural regions, have difficulty engaging in mass urban protests,” said Teresa Romero, the president of the United Farm Workers union, on Twitter. “But the movement in which we now take part stretches beyond city streets to the fields, orchards, and vineyards that feed this country.”

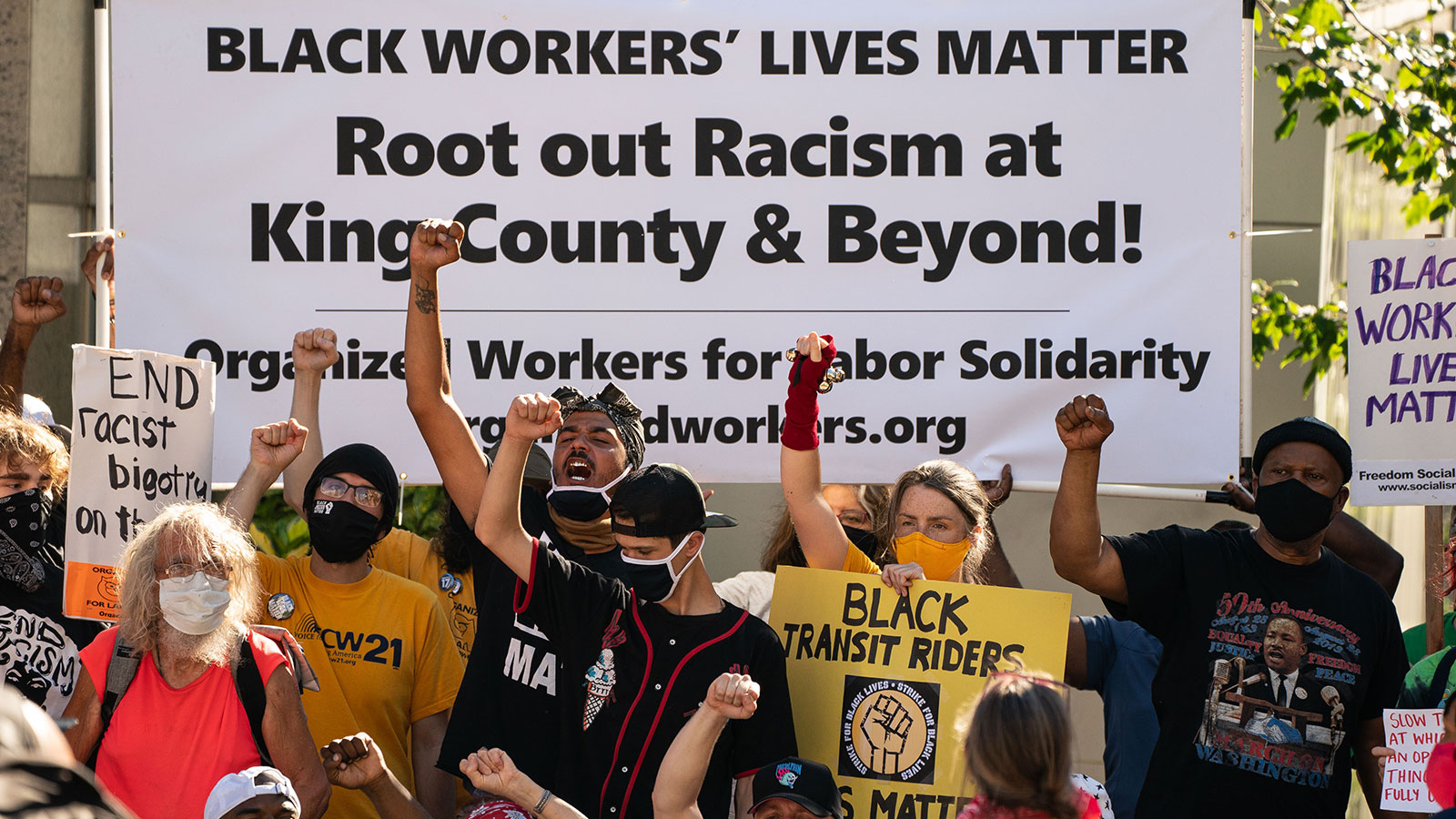

Tens of thousands of workers in health care, transportation, food services, and other fields joined the protest against racial injustice on Monday. The Strike for Black Lives website described it as a movement to “withhold our most valuable asset — our labor — in support of dismantling racism and white supremacy to bring about fundamental changes in our society, economy, and workplaces.”

This partnership between the UFW and the Black Lives Matter movement draws on a long history of alliances between farmworkers and racial justice advocates. Martin Luther King Jr., for instance, sent telegrams to famed agricultural labor leader Cesar Chavez in support of the 1965-1970 Delano grape strike and boycott, which was inspired in part by King’s Montgomery bus boycott. “Our separate struggles are really one,” King wrote, “a struggle for freedom, for dignity, and for humanity.”

The Delano grape strike, led by Chavez and Dolores Huerta, the founders of the UFW, fought for wage increases and labor protections for farmworkers. Later in life, Chavez fought for environmental health protections for farmworkers, raising awareness of the danger of pesticides in his famous 1986 speech, The Wrath of Grapes.

The UFW also has a deep history of collaboration with the Black Panther Party; in 1969, the two groups teamed up to boycott Safeway when the grocery store chain continued to sell California grapes. The UFW also supported the Black Panthers when the organization became a target of COINTELPRO, an FBI intelligence program aimed at surveilling and suppressing political figures and organizations deemed subversive, including King and Malcolm X.

Today, farmworkers and Black communities face similar structural injustices. Farmworkers, like the Black and Latino communities as a whole, face disproportionate risk associated with coronavirus, pollution, and climate change. Farmworkers have also long been left out of major labor protection legislation since the 1930s, in part because at that time, the majority of the nation’s farmworkers were Black.

The nationwide strike was organized by Service Employees International Union and supported by over 60 labor unions and social justice and racial justice organizations, including environmental organizations. The U.S. Youth Climate Strike Coalition stated on their website that Monday’s strike was an “opportunity to present a united front in the fight for racial, environmental, and economic justice as well as healthcare and immigrant rights.” 350.org, the Sierra Club, the Climate Justice Alliance, and the Union of Concerned Scientists also signed on in support of the strike.

“The farmworker movement and the civil rights movement has always stood together,” Romero said in a video on Twitter. “Only together can we move powerful forces, from boardrooms to the White House.”