The signs of climate change are hard to miss. The apocalyptic sight of a hazy, red-orange sky has become all too familiar as forests go up in flames. Mountains just don’t look the same after a summer of heat waves has melted their once-permanent glaciers, leaving strange, rocky bald spots. Some places are getting way too little rain, while others are getting rained on way too much, submerging basements and subway stations.

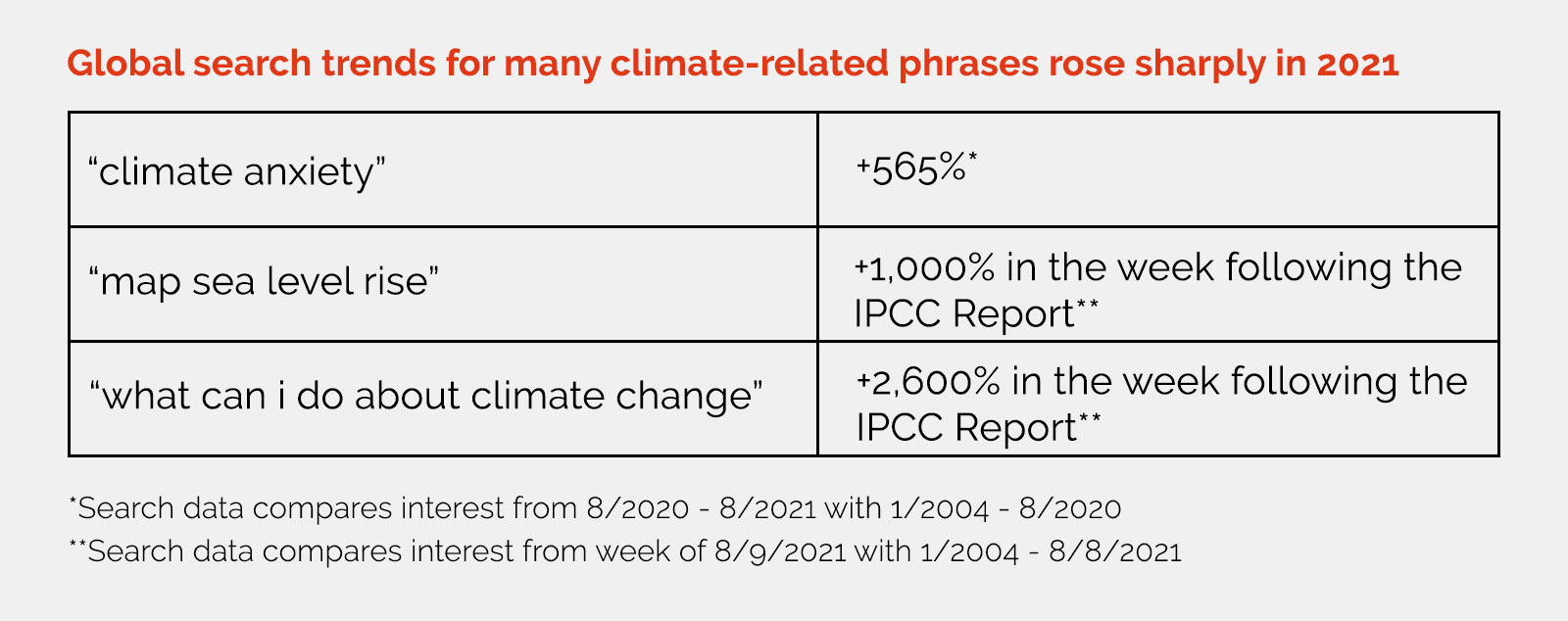

It’s enough to provoke a crippling anxiety, a deep dread about the future of our overheating planet. The proof: Google searches for “climate anxiety” have soared 565 percent over the past 12 months, according to data Google provided to Grist.

This sharp increase is “unusual,” said Simon Rogers, Google News Lab’s data editor. “There really seems to be this kind of existential fear.” Over the past year, he said, he’s seen big changes in what people have been Googling about climate change, a shift that reveals a public increasingly trying to grapple with what the crisis means for their lives and looking for answers.

“Whereas maybe before it felt like the climate was this abstract thing, now with fires and the floods and heat waves and so on, it’s become this real thing for people that they can see in a way that they haven’t felt before,” Rogers said.

There’s a growing recognition that climate change is here and happening in the United States. An all-time high of 70 percent of Americans are worried about it, according to a recent survey from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, which has been tracking levels of concern since 2008.

In September, the largest survey of its kind found that the climate crisis was causing widespread psychological distress for young people in 10 countries across the globe. Some 45 percent of teens and young adults said that climate anxiety was affecting their daily lives and ability to function; 56 percent said they thought that “humanity is doomed.” The average 6-year-old today will likely live through about three times as many climate-enhanced disasters — fires, crop failures, droughts, floods — as someone born in 1960, according to another recent study.

Search results offer a unique glimpse of the public’s mood, a window into private thoughts rather than ones tailored for public display on Twitter or Facebook. “There’s ubiquity to the way that people search which takes you beyond the echo chamber,” Rogers said. “When people are searching, it’s not about how they’re presenting themselves — it’s about something they genuinely care about and want to find out more about.”

Given the number of people Googling stuff every day, his team can’t analyze the total number of searches — instead, they use a measure called “search interest,” which shows how significant a specific query is compared to the overall volume of searches (globally or in a specific region).

This summer, search spikes coincided with extreme events happening around the world. In Greece, where thousands of islanders evacuated from fires in July and August, search interest for wildfires was up 40 percent compared to the average over the past 17 years, according to Google News Lab. Interest in heat waves also increased, going up by 6 times in the United Kingdom, where the national weather service issued its first-ever extreme heat warning in July, and 24 times in Russia as heat shattered temperature records in the Arctic Circle.

In August, a dire report from a United Nations-backed panel of scientists declared that climate change was “unequivocally” caused by humans and warned that greenhouse gas emissions were quickly destabilizing Earth’s ice, ocean, and land systems, with “irreversible” consequences. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report led to alarming headlines, with the BBC warning that this was “code red for humanity.” Interest in “what can I do about climate change?” hit an all-time high that week, increasing 27 times over the average since Google started keeping track in 2004. Rogers said that “personal action queries” like these — searches that start with “what can I do …” or “how can I …” have increased in the past year around climate change and other weighty problems, like the COVID-19 pandemic.

While climate change “feels like this huge, scary thing” you don’t have much control over, Rogers said, these practical “what can I do?” searches could be a way to exercise some amount of control over an uncertain future (even if it feels tiny in comparison to the scope of the crisis). People may be finding their own way to what many psychology researchers recommend as an antidote to climate anxiety: taking action.