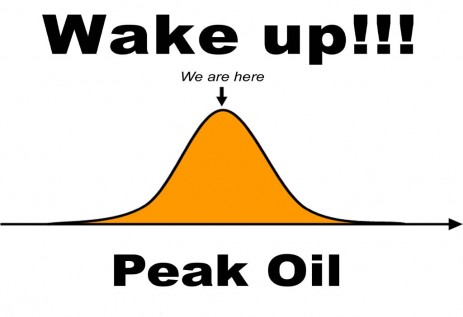

The further into the post-carbon age we grind, the more mainstream the notion of peak oil becomes. Long derided because it runs contrary to the only two things more American than football and corn syrup — that would be endless economic expansion and our right to commute 90 minutes a day, should we so choose — the recent uptick in gas prices has got the Canadians, at least, waking up to the reality of dwindling supplies of cheap oil.

A prominent energy scientist blames record-high gas prices on the approach of peak oil — a point when the world’s oil fields will pump out their maximum amount of oil, then gradually decline.

"There's no question that's what's causing it," says David Hughes, a recently retired geoscientist, who worked with the Geological Survey of Canada for 32 years.

His view defies conventional wisdom that turmoil in Libya is to blame.

…

"If we were not close to peak oil, [Libya] should not have made any difference," Hughes said. "There should have been enough spare capacity in Saudi Arabia to easily offset what's happening in Libya.

"That tells you something about how tight oil production is."

Hughes’ thinking on peak oil is a particularly tough sell in Canada, which is the No. 1 exporter of oil to the U.S. and has large, albeit difficult to extract, reserves in the tar sands of Alberta. Vaclav Smil, an expert on energy transitions and a professor at the University of Manitoba, says the result of peak oil will not be collapse, as pundits like Howard Kunstler argue, but a transition to alternative fuels.

"Most fundamentally, whenever any peak comes it will not be the end of the world as so many uninformed catastrophists insist.

"Natural gas can do anything oil can (except for flying, but that, too, after liquefaction), to say nothing about our inefficient use of gasoline," Smil wrote in an email to CBC News.