The effect of Tamiko Thiel’s augmented reality installation, which you view through your phone a la Pokémon Go, is fantastical. There are giant, whirling umbrellas of kelp floating overhead; planes of red algae swirling toward you at all angles; and massive purple blooms exploding out in infinite fields. When it comes to imagining our climate-changed future, Thiel’s vision is decidedly less post-apocalyptic wasteland, more Alice-in-Wonderland.

The setting for Gardens of the Anthropocene is arguably even more spectacular than the installation’s wild animations. Seattle’s Olympic Sculpture Park perches on the edge of the Puget Sound, and you’d be forgiven for missing the titular sculptures for the views of cerulean ocean, violet mountains, and jade-tinted islands. (I always do.) So it’s a bit counterintuitive to wander around staring into your phone when there’s that much jaw-dropping natural beauty at all angles.

But then, of course, if you do look up from your phone, you realize that the exquisite surroundings are everything that climate change threatens: Trees, water, air — and not least, all the people milling around you, phone-merized or not.

Thiel — who’s a Seattle native — has long straddled the line between artist and scientist, as she has engineering degrees from both Stanford and MIT. “It’s very hard, if you’re not a scientist, to get emotionally excited about scientific ideas.” And it can also be hard, as an artist, to get scientific concepts exactly right — which is why Thiel consulted with University of Washington ecologists Josh Lawler and Julian Olden for the project.

So it’s a scientifically accurate fact that in, say, 2100 we’ll be subsumed by armies of algae the size of a human head? No, but we will be seeing a lot more of it — and the havoc it’ll wreak on our seafood — than we are today.

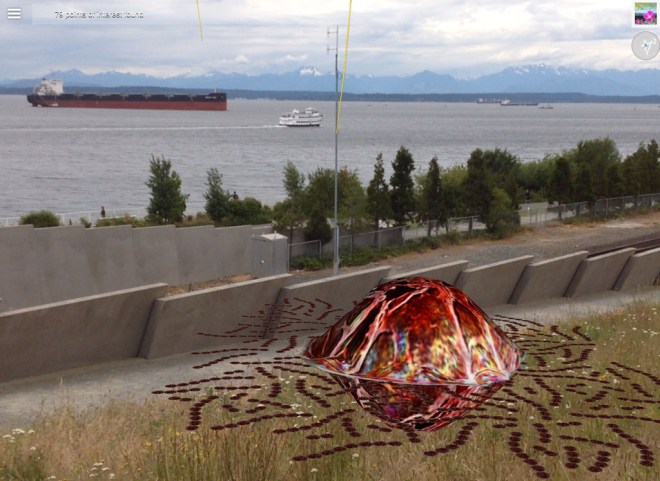

Red algae floating alongside the Puget Sound.Tamiko Thiel

“All my projects try and mix beauty with terror,” says Thiel. When did the terror hit her personally? When she was working on the design for the magnified Alexandria Castanela, or red tide: It makes shellfish poisonous, she tells me, and thrives in warming water.

“It was literally scary to me when I started working with this and looking at microscope images of the [algae’s] structure — it looks evil.”

When you consider that that algae could wipe out oysters as we know them — and all the cuddlier creatures that depend on them to live — they do seem more terrifying. As does the airborne bull-whip kelp, meant to suggest that the sea level could rise well over onlookers’ heads. But — as is Thiel’s self-described MO — the spectacle of them is also very beautiful.

“People who would not go into an exhibit that’s ugly and scary and only shows destruction,” she says. “I hope they’ll engage with this piece.”

I asked Thiel about her own emotional response to researching the destruction of Earth as we know it.

“I chose to work on my art instead of putting that energy into having kids,” she says, “I don’t have to confront my own personal children with the guilt [of screwing up the planet].

“I can take a long view and say, ‘The Earth has survived a lot of extinctions, and guess what? The Earth doesn’t give a damn. Other life forms will survive, and they will propagate and they will repopulate the Earth. There won’t be any humans. If we can’t save our planet, we don’t deserve to survive. But if I had kids, I would probably have a very different view of that.”

Bull whip kelp and Radar Camas blooms floating around Alexander Calder’s “Eagle.” Tamiko Thiel

And there, Thiel hit on — as much to my surprise as anyone else’s — my own emotional response to climate change. If there’s anything more powerful than the human ability to deny impending disaster, it’s the evolutionary devilry that’s recently been at work on my late-20s hormones. The most affecting thing I saw at Gardens of the Anthropocene wasn’t the animated blooms sprouting up around my feet or the exquisite vistas of the Olympics, but a young couple bouncing their cheerfully chattering child down the park path. “That — I want it,” my limbic system piped up.

The ethical dilemma of whether to have children is a real one — both from the standpoint of the additional carbon impact they might have on the planet (child-bearing increases your own carbon footprint by a factor of 5.7) and also subjecting a human to an uncertain-at-best planetary future. As Travis Rieder, a bioethicist who studies population ethics, said on an episode of the podcast The Adaptors: “For every child that we have, I think we ought to notice that the reasons against having a child absolutely swamp any reasons we have in favor of that child.”

But that reason — as Rieder, himself a father of one, experienced — tends not to win out against the force of instinct. Which leaves us in a seeming catch-22: How can we have our kids and a planet for them to live on, too?

Gardens, with its playful, brilliant animations, portrays a Wonka-esque world that children might love, so it’s a cruel irony that it would also be one that they would find very difficult to live in. In the end, it’s a sinister message: Play with that cute, bouncing algae all you like — you might as well have fun with the arbiter of your own demise.

If you’re in Seattle, Gardens of the Anthropocene will be on display at the Olympic Sculpture Park until September 30.