Photo by Lauri Kolehmainen.

My friend Emma Marris wrestles with giant Burmese pythons. Well, OK, not literally. But in her book Rambunctious Garden (which you should all read this very minute), she takes on the long-held idea of nature as a pristine, unspoiled, and distant place.

She asks if we can learn to see nature almost everywhere — in highway medians, urban parks, even an Everglades infested with exotic, predatory snakes. She argues that while we can and should continue to push for the protection of large, relatively unaltered landscapes, we shouldn’t necessarily try to restore them to pre-Columbian conditions — and we definitely shouldn’t allow the fight for big parks and wildernesses to limit our notion of nature. For if we see nature only as a place apart from us, she says, we’ve already lost it to climate change and any number of other forces. And who wants to join a lost cause?

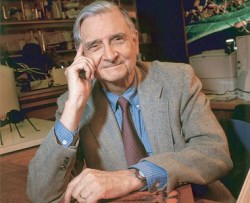

This summer, Emma had another public wrestling match, not with a Burmese python but with the preeminent biologist and conservationist E.O. Wilson.

During a panel at the Aspen Environment Forum in Colorado, as she describes here, Emma piqued Wilson with her talk of making more nature — of expanding our definition of the natural world to include places humans have invaded, altered, and restored. Spending billions trying to restore “purity” to places like the Everglades, she said, was a lost cause. Better to invest in upslope reserves, and learn to admire the tenacity of invasive species.

E.O. Wilson: not amused.

“Where do you plant the white flag that you’re carrying?” Wilson asked irritably.

Emma, who got the last word, quoted Joseph Mascaro, an ecologist she interviewed for her book. Mascaro studies the ecological attributes of “novel” ecosystems heavily influenced by human activities. “When people accuse him of admitting defeat,” said Emma, “he says, ‘I never took up arms. I’m playing a different game here.'” His message, she says, is “I’m here for nature, not for 1491.”

Me, I had the luxury of watching from the audience. At times, Emma and Wilson seemed to be arguing over a false dichotomy. After all, both spoke passionately about the importance of all types of nature, from macro to micro to humble to grand, and they agreed that all deserve appreciation. What’s so wrong with defending a few pythons, then, especially if it means bringing nature a little closer to our everyday experience?

But from Wilson’s perspective, Emma’s view is heretical. By arguing that the project of conservation should extend from the peaks of national parks into the sloughs of Seattle, treating different places in different ways for different reasons, Emma risks diluting its urgency. If nature really is found almost everywhere, one might well wonder why we need to work so damn hard to save the best bits.

The deepest divide may be generational. Wilson, now in his 80s, has explored some of the most biodiverse places in the world. He knows, from long experience, how much effort it’s taken to protect and begin to restore just a handful of them. He may worry that Emma is leading younger conservationists into a kind of moral relativism, asking them to bestow equal value on vegetable gardens and old-growth forests. Emma, in her 30s, doesn’t want to do that — but neither does she want to simply inherit her predecessors’ endgame, and watch the few remaining places free of human footprints change, shrink, and disappear.

Wilson may sound like the idealist and Emma the realist, but in the end Emma is the true optimist. She hopes that conservationists of her generation will have the energy and money and numbers to work for nature on many fronts: not only by protecting our largest and richest reserves of biodiversity but also by restoring prairies, transforming urban rivers, and experimenting with old and new ways to save species, habitats, and the water we drink and air we breathe. To Wilson, that might sound naïve, or impossible, or a lot like giving up. To Emma, it sounds like a lot of hard work — and a hell of a lot of fun.