A community-supported agriculture (CSA) share can be a culinary battle royale. Every other week, it’s you versus a mystery box. No tap outs, no substitutions. Just a bitter melon so fresh, you wouldn’t dare toss it out. And while there’s something to be said for experimentation, sometimes you just want something a little more familiar, something easy to pack for lunch, something the kids will touch. Or maybe you’re just having a mad craving for heirloom radishes?

That’s where Plovgh enters the picture. The online marketplace soft-launched in November 2011, and hopes to offer an alternative to the traditional CSA and farmers market systems by allowing customers to order exactly what and how much they want from local farms while still getting it delivered to their neighborhood. Sites like Local Dirt and Local Harvest connect online customers to farms, but neither will bring groceries to your neighborhood bar. And while food hubs can distribute food to schools, restaurants, and other groups with big local food needs, Plovgh (pronounced “plow”) brings all those perks to individuals — even those who might only cook once a week.

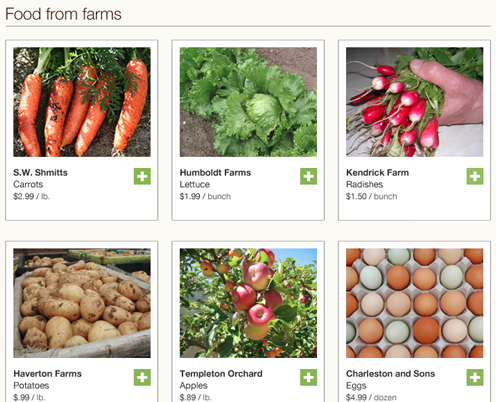

Here’s how it works: Farmers report what they’ll be harvesting for the week on Monday afternoon and customers order exactly which foods they want from Tuesday through Thursday for weekend pick-ups. The website will undergo plenty of spruce-ups through the summer, but the basic functions are up and running. Organic produce, pasture-raised meat, and foodie extras like pickles, maple syrup, and honey are listed based on the pick-up spot (usually bars or cafes — nothing washes down local produce like a noontime beer), and sorted by neighborhood and time. You click, pay, and voila: A few days later your food arrives down the block.

The system works for farmers, too. Often, they plant and harvest food to bring to market without a guarantee that it will sell. As farms with CSAs work to provide more flexibility for consumers, that’s shifting for the better. In the case of Plovgh, the company has also coordinated transportation efforts, so that they can essentially carpool their food. (Sadly, this still wouldn’t qualify solo drivers for the carpool lane.) Sometimes an area farmer does the driving; other times, it’s just someone who lives in the neighborhood and is looking for extra income.

“Nothing is harvested until it is sold, so we waste less produce and labor than harvesting for a farmers market,” says Amoreen Armetta, who runs the New Paltz, N.Y., farm Partners Trace with her partner Tierney Dearing Medick. “Plovgh also picks up our orders so we don’t have to drive the two hours down to the city,” she adds.

The food is offered at the same or lower prices than one would find at the farmers market. That’s because like food hubs, this process cuts down on time spent selling food and prevents waste. Plovgh doesn’t need a building to operate out of, either; it relies on existing public spaces like restaurants and community centers. By using technology for many of the logistics — like taking and organizing orders, scheduling pick-ups, and delivering to the customer — Plovgh is able to cut down significantly on costly people power.

“The supply chain mentality is emblematic of an old way of doing business that is becoming irrelevant,” says founder Elizabeth McVay Greene. “Food hubs take the supply chain notion and apply it to local food. We’re trying to blast that whole notion of a supply chain out of the water.”

Currently, Plovgh is only operating in pilot mode, with approximately a dozen farms in the greater New York City area. But Greene hopes to fully develop the website by the end of the year, so don’t be too surprised if Plovgh networks start popping up in other U.S. cities soon. (Look out, Atlanta! Greene is in talks with nearby farmers.)

New York is a great testing ground for the program because several aspects of traditional CSA drop-off programs — like large upfront payments — make them “especially hard in big, urban areas,” Greene says. The weekly commitment and lack of choice with CSAs throw red flags up faster for New Yorkers than most other eaters, especially younger urbanites. “It’s a lot to ask of someone whose life is ever-evolving,” she says. “That lack of flexibility is weird because we’ve become used to an age of choice.” It helps, at least, that many New Yorkers are already aware of CSAs and comfortable buying food directly from the farmer ― which isn’t necessarily the case, she says, in states like Mississippi.

The final goal for Plovgh is to provide a technological platform for farmers, customers, transporters, and potential pick-up sites across the U.S. and beyond, which would allow them to coordinate amongst themselves. “The notion is that a farmer in India could use this and sell to people in Mumbai,” Greene says. In fact, she was inspired to create Plovgh after working with rural cotton farmers in India to help bring their products to urban markets. “It’s a very distributed model. We’re taking resources that already exist at the farm and neighborhood level and putting them to use.”