The vision

“People have spent time bobbing their heads to our stories of this despair and not seeing it as a call to action. Now, I think, is this generation’s opportunity to go back and look at 50 years of these unsolicited, sometimes unfiltered and raw stories of environmental injustices and climate change.”

Michael Ford, “Hip Hop Architect”

The spotlight

Earlier this month, hip hop marked its 50th anniversary with a massive concert at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx — the New York City borough where the genre was born. As the hip hop community celebrates half a century of music, culture, and innovation, for many it’s also a moment to reflect on the genre’s long history of activism.

Hip hop has always been an inherently political movement. Although some of the genre’s hits focus on party culture and conspicuous consumption, its verses have been used to speak out about racism, oppression, police brutality, and a host of other issues, including environmental justice.

Writer Zack O’Malley Greenburg has been covering the business of hip hop and its stars since 2007, including authoring the 2015 Jay-Z biography Empire State of Mind. During that time, Greenburg says, hip hop has received attention for the wealth it has generated for communities of color, especially as some of its most prominent moguls have begun investing and launching companies. “What’s gotten less notice is how major artists — and not-so-major-artists — have been very effectively advocating for social justice and action, notably around climate,” he says. But hip hop stars who have spoken out or donated large sums to climate causes haven’t received the same recognition as the Leo DiCaprios of the world.

Greenburg wrote a feature for Grist exploring the often underappreciated history of hip hop and environmental advocacy — as well as the construction of the Universal Hip Hop museum, set to open in New York’s massive Bronx Point development next year. (The museum is designed by architect Michael Ford, who was featured on our 2019 Grist 50 list.)

“The Universal Hip Hop Museum felt like the perfect lens [through which to examine the genre’s activism], as it unites old school and new school, and happens to be in a flood zone,” Greenburg said, noting how hip hop’s birthplace remains vulnerable to climate impacts. As those effects intensify, and climate awareness grows, Greenburg predicts that the hip hop community’s response will as well. “Maybe we’ll see more acts greening their tours or lowering the carbon footprint of products they endorse,” he says, “or investing in climate-tech startups and elevating them with the same marketing prowess they’ve used to boost everything from apps to alcohol.”

In the excerpt below, Greenburg examines the longstanding connections between hip hop and environmental justice.

![]()

Hip hop has been a climate voice for 50 years. Why haven’t more people noticed? (Excerpt)

Hip hop dates back to August 11, 1973, when Clive “DJ Kool Herc” Campbell hosted a back-to-school party in a rec room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx. His revolutionary innovation: physically manipulating two copies of the same record in real time to extend the “breaks,” or the danceable interludes, of popular songs.

Back then, the genre’s activism centered around the built environment, calling attention to egregious living conditions in places like the South Bronx. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s 1982 classic “The Message” served as perhaps the most potent example: “I can’t take the smell, can’t take the noise / Got no money to move out, guess I got no choice.”

“What is today called the climate crisis was in full effect in the underserved communities when this song was released,” said the Universal Hip Hop Museum’s Kate Harvie. “Whatever has been happening to the climate was first to affect unprotected and unrepresented lands.”

But as hip hop heated up through the 1990s, environmental advocacy took a back seat, at least until Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. The storm uprooted scores of New Orleans residents, including the founders of Cash Money Records — whose roster, at the time, included Lil Wayne, Nicki Minaj, and Drake. (The company has since decamped to Miami.) Chief executive Bryan “Birdman” Williams told me he lost “20 houses, 50 cars, and memories” in the disastrous flood surge.

Artists like Jay-Z and Diddy donated seven-figure sums to Katrina relief efforts. Others, including Lil Jon and Ludacris, performed on charity telethons to aid disaster recovery. During one, Kanye West, incensed over the federal government’s feeble response in communities of color in New Orleans, famously declared “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people.”

It wasn’t just musicians who were incensed. Reverend Lennox Yearwood Jr., a Louisiana native and president and CEO of the nonprofit group Hip Hop Caucus, also noted the disproportionate damage to New Orleans’ poorest neighborhoods. “Climate justice is racial justice, and racial justice is climate justice,” said Yearwood. “It was the Ninth Ward that was devastated and not the French Quarter.”

Yearwood got his start as a minister in 1994 and served as director of student activities at the University of the District of Columbia before signing on to run Diddy’s Vote or Die! initiative ahead of the 2004 presidential election. He saw unique potential in the hip hop community to mobilize for political, social, and environmental causes — including climate change.

Black neighborhoods often sit in flood-prone areas, a consequence of historic segregation. Environmental racism — which also includes dumping of toxic materials and building highways that cut through communities of color — has led to higher rates of diseases from asthma to cancer. And climate change will continue to have a disproportionate impact, even beyond flooding: If the planet warms by just 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees F), Black people are 40 percent more likely to live in areas with deadly heat waves.

Through the Hip Hop Caucus, Yearwood and others have raised awareness of these realities while also advocating for solutions. Early initiatives included the Green the Block campaign in the mid-aughts, when the Caucus worked with Drake during his tour to “educate his fans about the benefits of going green.” Post-Katrina, Yearwood established the Gulf Coast Renewal Campaign to support survivors. In 2013, the Caucus teamed up with the Sierra Club to protest the Keystone XL pipeline, bringing some 35,000 people to the National Mall in Washington — then the largest documented climate protest.

The Hip Hop Caucus’s push for climate justice circled back to the music. In 2014, the group helped organize HOME (Heal Our Mother Earth), an album dedicated to saving the planet. On the track “Trouble in the Water,” the rapper Common delivered the line: “We think our opponent is overseas / But we messin’ with Mother Nature’s ovaries.”

— Zack O’Malley Greenburg

Check out the full story on our site to read about more ways the global hip hop community has led on environmental activism, and how climate change has influenced the organizers of the Universal Hip Hop Museum.

More exposure

- Read: highlights from hip hop’s 50th anniversary celebrations (NPR)

- Read: about the Universal Hip Hop Museum’s president, Rocky Bucano (NYT)

- Read: more about the longstanding environmental advocacy of Black musicians (Atmos)

- Listen: to HOME, the 2014 climate album spearheaded by the Hip Hop Caucus

A parting shot

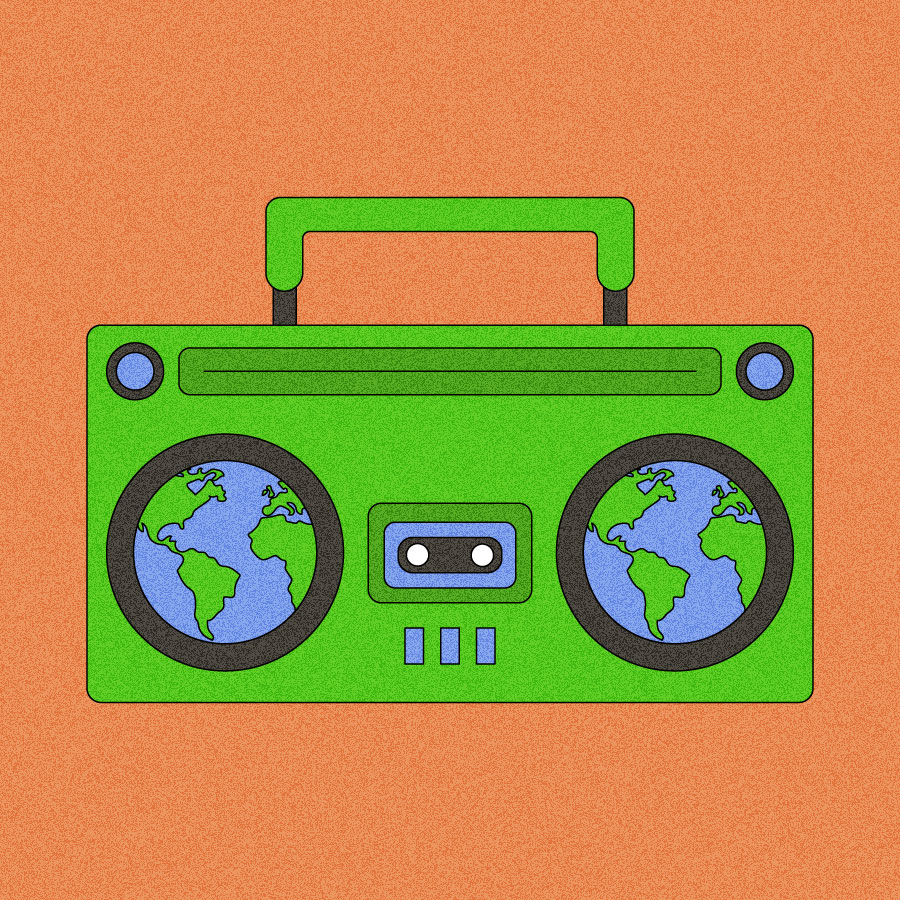

Rihanna performs during the 2007 Live Earth concert, a 24-hour multicity event to raise awareness and funds for the climate crisis. Other acts included Snoop Dogg, Pharrell, Madonna, and Metallica. As Greenburg notes in his piece, Rihanna also donated $15 million to environmental justice groups last year through her Clara Lionel Foundation, which focuses on climate resilience and emergency preparedness in the Caribbean.