The vision

“We know that there are actual real-life impacts between communities that don’t have access to the health benefits of trees and those that do.”

Benita Hussain, tree equity lead at American Forests

The spotlight

This summer, when the mercury surged in Seattle, I found myself constantly crossing over to the shadier side of the street on walks with my dog. The difference was noticeable, even on the same block.

Trees, which cool their surroundings by providing shade and by pulling heat from the air as they absorb and release water, can lower temperatures by around 10 degrees Fahrenheit in city neighborhoods. Research also suggests that being around trees reduces stress and can improve other health outcomes — plus, they store carbon, reduce runoff, act as wind and noise breaks, and increase property values. But the benefits of trees are not felt equally.

“We have the data and research showing that there are parts of cities — and 80 percent of America lives in cities — huge swaths of them don’t have trees. And that is generally correlated with areas that have underserved and disadvantaged communities,” says Benita Hussain, tree equity lead at American Forests, the oldest conservation organization in the U.S. “If we don’t actually tackle the equity issue that we are facing right now, we’re going to be dealing with far more death and disease related to climate.”

Tree equity, a term coined by American Forests, is the idea that all residents deserve the same access to tree cover and the health and infrastructure benefits it confers. That requires focusing on the areas that currently lack foliage, due to historic disinvestment and racist practices like redlining. “I have the data saying [there is] 38 percent less tree canopy in communities of color, leading those communities to have 13-degree-Fahrenheit hotter temperatures,” Hussain says. “These are real life-and-death issues, and the new data sets are allowing us to build that case for communities.”

American Forests recently launched a new version of the Tree Equity Score, its publicly available mapping tool that measures tree canopy along with other factors, like health, income, and surface temperatures, to determine the need for investment in trees in a given area. The scores range from 0 to 100, with lower numbers representing greater need. With the newest update, the tool now covers all urban areas in the country, going from 500 metro areas to 2,500, along with updated census data and improved heat mapping.

“The whole premise behind it is: Let’s provide you with the best and most exact data for cities to know where to invest in trees and how their investments will actually benefit people, down to the parcel level,” Hussain says. Originally launched in 2021, the Tree Equity Score has already been used to inform tree canopy goals in a number of cities, including those in the state of Washington, which we’ve covered in the past.

The city of Detroit has used the data as an advocacy tool, says Jenni Shockling, a senior manager of urban forestry for American Forests in Detroit. “We generally knew, or at least we felt that we were seeing disparities between the tree canopy coverage, and that it tended to be by race and income level,” she says. “And now we can actually show that.”

Last fall, Detroit launched a tree equity partnership along with American Forests, DTE Energy, and a local nonprofit called The Greening of Detroit, aimed at planting more than 75,000 trees in disadvantaged neighborhoods over a five-year pilot. Detroit is also currently working on building out a Tree Equity Score Analyzer, an additional layer to the tool that will enable the city to add local landmarks and model different scenarios for tree planting on a block-to-block level.

Prior to launching the tree equity partnership, the city and local organizations were planting largely to keep up with the removal of dead trees. “Historically, combined, that was about 2,000 trees a year, and we were losing about 4 to 5,000 trees a year,” says Shockling, who previously worked on The Greening of Detroit’s field crew. “We were never going to get ahead of that curve.” But since the tree equity partnership launched, Shockling says, their team, largely composed of individuals returning from incarceration, has increased tree planting in Detroit by nearly 500 percent.

The program also includes a maintenance plan for at least the first three growing seasons, something that helps to assuage some residents’ concerns about who is responsible for tending to newly planted trees, Shockling says. Though, in some cases, community members are excited about taking that work on themselves. In one of the program’s pilot areas, a resident volunteered to water newly planted trees near their home, and received a stipend for hoses and water to support their efforts.

So far, Shockling says, most Detroiters have welcomed the tree planting. “Our crew has had people pull up and clap for them,” she says. “Every time I’m out on-site, somebody comes by and wants to talk. They usually say, immediately, ‘I love this.’ And then they tell me who in their family has asthma.”

The air-cleaning benefits of trees are what originally got Shockling interested in this work. One of her children was born with special medical needs, which meant that Shockling spent a great amount of time in children’s hospitals, where she was struck by the prevalence of childhood asthma. “It just breaks my heart to see the asthma rate, and the fact that it’s by zip code and where you’re born in the city kind of indicates what your quality of health and life will be,” she says. With her son’s medical condition, there wasn’t an obvious prevention measure. But “I saw that there was something that could be done about asthma.”

Of course, planting new trees does take time, Hussain says. And in some neighborhoods, the level of canopy cover that can be achieved is limited by things like the density of housing and other buildings, as well as climatic conditions like rainfall. The Tree Equity Score map includes different canopy goals for different areas based on these kinds of factors.

And while trees alone won’t solve the increasing problem of heat, or a city’s air quality, Shockling, Hussain, and other advocates view trees as crucial infrastructure for healthy cities. “The tree is the thing that you see, but the impact is so much greater,” Shockling says. “In addition to what they do for the air, they benefit the soil and the water and in my opinion, every living thing in between. So it’s almost like an obvious solution to me — why wouldn’t you plant a tree?”

— Claire Elise Thompson

More exposure

- Read: more about the Detroit Tree Equity Partnership (Planet Detroit)

- Read: about incoming IRA funding for urban forestry (Frontier Group)

- Read (or listen t0): a recent story about tree equity efforts in Boston (WGBH)

- Explore: an analysis of tree equity maps (NYT)

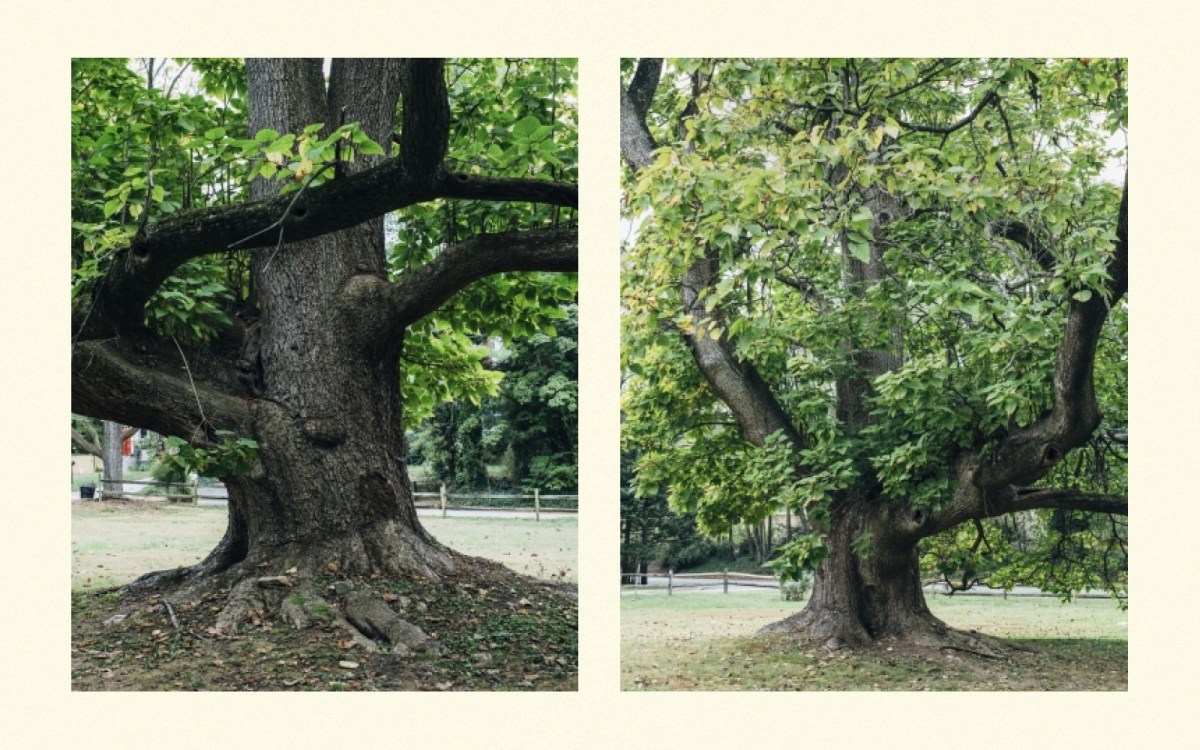

A parting shot

Another part of American Forests’ work is maintaining a national registry of “champion trees” — the largest known trees of a native or naturalized species in the U.S. — like this Southern catalpa tree in Baltimore County.