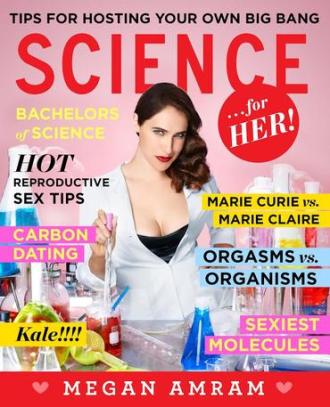

Describing the premise of Science … For Her! is an exercise in combining words that don’t readily make a lot of sense together. “It’s like a textbook, that’s written in the voice of a Cosmopolitan editor — if Cosmopolitan editors were certifiably insane,” I said to a friend, who just kind of stared at me. I was trying to explain my enthusiasm about interviewing the author, 27-year-old comedian Megan Amram.

Amram, like all great things, got her start on Twitter, and then began writing for the undeniably hilarious series Parks and Recreation. Science … For Her!, which came out earlier this month, is her first book. The splashy quasi-textbook is a satirical take on the very, very tired trope of women being unable to understand science — or math, or economics, or anything remotely empirical. Amram breaks down a number of rudimentary scientific concepts, all through the bizarre lens of a women’s magazine.

Some examples: Outfit suggestions for global warming! (“+ 20° FAHRENHEIT: Most of Africa and Australia is now unlivable for humans. Half of the human population has been wiped out due to lethal heat-stress levels. Try a super-light linen sundress in white or light yellow for a summery splash of color.”) A lesson in basic chemistry — tailored to the female reproductive system! (“THE PERIOD! ICK! TABLE What would a women’s science book be without a spotlight on periods? In this segment, I show a periodic table where every element represents a different aspect of menstruation!”) Winter’s sexiest molecules! (Self-explanatory.)

Some examples: Outfit suggestions for global warming! (“+ 20° FAHRENHEIT: Most of Africa and Australia is now unlivable for humans. Half of the human population has been wiped out due to lethal heat-stress levels. Try a super-light linen sundress in white or light yellow for a summery splash of color.”) A lesson in basic chemistry — tailored to the female reproductive system! (“THE PERIOD! ICK! TABLE What would a women’s science book be without a spotlight on periods? In this segment, I show a periodic table where every element represents a different aspect of menstruation!”) Winter’s sexiest molecules! (Self-explanatory.)

I got to chat with Amram about how, exactly, she came up with the premise for this book, why science is funny, and what pisses her off more than anything. Here’s a lightly edited and condensed version of our conversation:

Q. So why did you want to write Science … For Her!?

A. First of all, I wanted to write a comedy book, and I wanted to make people laugh — that was my first and foremost goal. But I thought that the aesthetic of a woman’s magazine would look really funny and be fun to work on. There’s a funny convergence there, of textbooks and magazines organized in very similar ways with diagrams and sidebars.

And the satire of making a woman’s textbook was very clear to me. If you follow the line of people in the media saying that women don’t understand math or science or how to drive — or any number of things — out to its furthest point of logic, then women don’t understand anything about the world. And I’ve sort of wanted to play devil’s advocate there.

Q. How have you experienced that firsthand — the public questioning of women’s ability to understand empirical things?

A. I went to Harvard, and right before I started there Larry Summers, then the head of the school, had said that women might have less aptitude in the whole career of math and science. That’s just not taking so many things into account — like women aren’t told when they’re little girls that they should go into [STEM fields], and a whole slew of other things. But I think that’s what frustrates me — [public figures saying] these things that are so uninformed. I want to know what goes through their heads — like, what made you think you could say this without looking anything up?

Q. Alright — so how would you change that? How would you get girls into science?

A. I think just such an [important] thing is to hear is that it’s something you should do as a very young girl. This book is very dirty and violent, so it’s not really appropriate for middle schoolers, but I do kind of hope that girls who are too young get their hands on it. Hopefully when they read it, it will occur to them that you shouldn’t just take things for granted — like, that women do certain sorts of jobs, for example, or that magazines are never sexist. I think that as a young person, you’re rarely questioning the things around you — but girls need to question the idea of what they should and shouldn’t do.

Q. Do you think that humor and science should intersect more?

A. I’ve always been very interested in science, but some people see it as a humorless thing, I imagine. Which is not true — so many scientists have great senses of humor. Albert Einstein had a great sense of humor. [Scientists don’t fit] the stereotype of a person in a dark room who doesn’t talk to anyone, doing calculations.

Q. I mean, there’s a lot that’s funny about science right now — mainly the fact that it’s being ignored by the people governing our country. That’s kind of funny, in an awful, absurdist way.

A. Yes — it feels like a Beckett play or something. It’s like, “Oh, so I guess I need to not get angry and I need to give in to the fact that the rules of logic don’t apply to the world we live in!” But then you have to think, “No, we have to keep fighting these people, because if you don’t, then they just win.”

Q. Like climate change deniers taking over the Senate Environment Committee?

A. It’s my least favorite thing — I can’t even describe to you how angry I am just thinking about it. Climate change and the anti-vaccine movement are the two things that probably get me the angriest, including people who have slighted me. I have nothing new to say, except for: 1. Look around the world. Just literally look outside your window and tell me that things have not changed in your lifetime, in terms of climate. And 2. Why not prepare for the worst?

It appears that some politicians believe that scientists are trying to trick them. What — do you think scientists are all these sneaky little rats who are thinking, “Oh, these guys bullied me growing up, and now I’m gonna trick ’em — take their money away!” It’s so insane to me.

Q. So I’m sure you’re familiar with this refrain of conservative politicians saying, “I’m not a scientist, so I can’t comment on climate change.” How would you respond to their making that claim over and over again?

A. I would say, “Oh, don’t sell yourself short! Of course you are! Don’t say that about yourself! Anyone’s a scientist if they believe!”