This piece was co-written with Erica Goad, an intern with the Energy team at the Center for American Progress, which originally published this post.

Wildfires blaze near San Diego.Photo: slworking2Hurricane Claudette hit the Florida panhandle Sunday, lashing it with heavy rains. Hurricane Bill is gathering strength in the Atlantic, and is “poised to grow into a major storm” later this week. It could hit the East Coast as a Category 3 storm with 121-mile-per-hour winds. Meanwhile, “hot, dry winds and high temperatures continue to fan wildfires across California.” Recent wildfires in the state have burned over 100,000 acres.

Wildfires blaze near San Diego.Photo: slworking2Hurricane Claudette hit the Florida panhandle Sunday, lashing it with heavy rains. Hurricane Bill is gathering strength in the Atlantic, and is “poised to grow into a major storm” later this week. It could hit the East Coast as a Category 3 storm with 121-mile-per-hour winds. Meanwhile, “hot, dry winds and high temperatures continue to fan wildfires across California.” Recent wildfires in the state have burned over 100,000 acres.

These events have a common thread. The ferocity of tropical storms and spread of wildfires will increase as the planet warms. Nonetheless, House opponents of the American Clean Energy and Security Act, H.R. 2454, spoke during the bill’s June debate as if there were little urgency for action or costs to delay reductions in global warming pollution. Rep. Joe Barton (R-TX) raised serious doubts about the “effectiveness of any carbon emissions reduction scheme.”

Recently Senator John Barrasso (R-WY) cited a debunked, unscientific report from an EPA economist to claim that the science on climate change was “inconclusive at best.” But there’s a growing body of scientific evidence that global warming has already harmed the United States. And the soaring number of presidential disaster declarations reflects the growing economic, social, and environmental harms from global warming. These trends should serve as another catalyst for action by the Senate this fall as it debates the American Clean Energy and Security Act.

The Bush administration’s U.S. Climate Change Science Program, or CCSP, working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, gathered the latest scientific research in its June 2008 report, “Weather and Climate Extremes in a Changing Climate.” The report’s conclusion:

In the future, with continued global warming, heat waves and heavy downpours are very likely to further increase in frequency and intensity. Substantial areas of North America are likely to have more frequent droughts of greater severity. Hurricane wind speeds, rainfall intensity, and storm surge levels are likely to increase. The strongest cold season storms are likely to become more frequent, with stronger winds and more extreme wave heights.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s “Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States” report, released on June 16, 2009, provides reams of scientific data about warmer temperatures, more frequent floods and droughts, more damaging wild fires, and other serious impacts. For example, some of the clearest results from the research show that rainfall patterns will significantly change. These events would only add to the growing number of disaster declarations, which have dramatically risen in the last three decades.

Presidential disaster declarations on the rise

Since 1969, presidential disaster declarations for floods, storms, and wildfires rose by 43 percent. An increase in human fatalities, property damage, and disrupted business has accompanied these disasters, as reflected in the spiking cost of insured losses from catastrophes, which totaled around $3 billion in 1980 and has since risen to more than $70 billion (in 2005 dollars) in 2005. The most recent report by scientists with the International Panel on Climate Change shows that the predicted increase in natural disasters is indeed already unfolding.

The average number of presidential disaster declarations per month in office steadily rose, beginning with President Ronald Reagan (see below). Reagan’s relatively low rate of declarations may have reflected his antigovernment philosophy—he may have been more hesitant to use this authority since he generally opposed government involvement for many purposes. After Reagan, the rate of declarations increased steadily from President George H.W. Bush through President George W. Bush. And President Barack Obama has a higher rate still, even though this data is from his first five months in office in 2009, including eight declared disasters in June alone. Examining the data by year reveals the upward trend in declarations beginning in 1989.

The amount of money appropriated to federal disaster relief programs has also increased, according to the Federation of American Scientists. The Stafford Act, passed in 1988, required the setup and compliance of cost-sharing among states, the federal government, and disaster relief agencies, and set a cap at $5 million per disaster of federal money (although the president can and frequently does request more money from Congress if necessary). According to the Public Entity Risk Institute at the University of Delaware, total federal disaster spending from 2000 to 2007 cost over $81 billion, or $736 per American household. This is a conservative estimate because FEMA spending for some disasters less than five years old (including Hurricane Katrina) is ongoing.

NOAA maintains a comprehensive record of weather and climate, and published a graph on federal disasters that cost over $1 billion in the last 28 years. The graph shows a consistent rise in the number of events over $1 billion since 1980.

Declarations for more destructive and costly hurricanes

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was one of the most destructive and expensive natural disasters in U.S. history, claiming more than 1,800 lives and causing an estimated $134 billion in damage. Even without 2005—which also included a number of other severe storms—spending on federal hurricane disaster relief is rising. This trend will continue if global warming pollution continues to heat the atmosphere, leading to more severe storms.

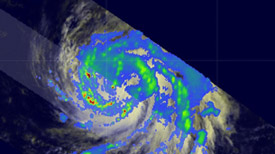

A radar image of Hurricane Bill. Over the weekend Bill grew into the first hurricane in the Atlantic this season.Source: NASANOAA’s recent report outlines how “hurricane rainfall and wind speeds are likely to increase in response to human-caused warming” (see page 35 of the report for graph “Observed Relationship between Sea Surface Temperatures and Hurricane Power in the North Atlantic Ocean”). CCSP also warned of higher-intensity storms in the future, noting that analyses of model simulations suggest that for each 1ºC (1.8ºF) increase in tropical sea surface temperatures, core rainfall rates will increase by 6 percent to 18 percent, and the surface wind speeds of the strongest hurricanes will increase by about 1 percent to 8 percent.

A radar image of Hurricane Bill. Over the weekend Bill grew into the first hurricane in the Atlantic this season.Source: NASANOAA’s recent report outlines how “hurricane rainfall and wind speeds are likely to increase in response to human-caused warming” (see page 35 of the report for graph “Observed Relationship between Sea Surface Temperatures and Hurricane Power in the North Atlantic Ocean”). CCSP also warned of higher-intensity storms in the future, noting that analyses of model simulations suggest that for each 1ºC (1.8ºF) increase in tropical sea surface temperatures, core rainfall rates will increase by 6 percent to 18 percent, and the surface wind speeds of the strongest hurricanes will increase by about 1 percent to 8 percent.

There have been more hurricane disaster declarations in recent years. From 1954-1997, there was only one year—1985—with more than 10 hurricane disaster declarations. There are five such years from 1998-2008.

Declarations for more frequent and intense wildfires

The recent California wildfires destroyed over 100,000 acres and forced several thousand people to flee their homes. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger declared a disaster in Santa Cruz County. These fires are a harbinger of a global warming future.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, has reported “with very high confidence” that “disturbances such as wildfire and insect outbreaks are increasing and are likely to intensify in a warmer future with drier soils and longer growing seasons.” Wildfire frequency and intensity are also related to the compounding effects of drought. For example, the devastating southern California wildfires have been linked to severe drought conditions.

The IPCC found that compared to the earlier 17-year period, the warmer temperatures of the most recent 17 years were linked to a 78-day increase in the length of the fire season, a fourfold increase in the number of fires, a fivefold increase in the time needed to put out the average wildfire, and that 6.7 times as much area is burned. The frequency of wildfire disaster declarations has also increased dramatically over the past several decades. To some extent this reflects an improvement in reporting structure and an expansion of development into the Wildland-Urban Interface, or WUI, which increases wildfire damages to homes and property.

The U.S. National Forest Service allocated nearly 45 percent of its budget to fire mitigation in fiscal year 2009, and has requested more in FY2010 in light of increased fire danger from conditions such as massive tree die-off due to unprecedented climate change-linked insect outbreaks like the mountain pine beetle.

Declarations for more floods

An increase in global temperatures will also lead to an intensification of the hydrologic cycle. This is because an increase in surface air temperature causes an increase in evaporation and generally higher levels of water vapor in the atmosphere. In addition, a warmer atmosphere is capable of holding more water vapor. The excess water vapor will in turn lead to more frequent heavy rainfalls when atmospheric instability is sufficient to trigger precipitation events. “Global warming is partly to blame for these heavy rainfall events,” said Dr. Amanda Staudt, climate scientist, National Wildlife Federation. “Warmer air simply can hold more moisture, so heavier precipitation is expected in the years to come.”

Intense precipitation can cause flooding, soil erosion, landslides, and damage to structures and crops. According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program, heavy downpours that are now one-in-20 year events are projected to occur as frequently as one every four years by the end of this century, depending on location, and the intensity of heavy downpours is also expected to increase. Global warming can bring heavier rainfall because warmer air can hold more water, causing events that are projected to continue increasing under a variety of climate scenarios. For every 1 degree of Fahrenheit warming, atmospheric water vapor increases by three to four percent. The one-in-20-year heavy downpour is expected to be between 10 and 25 percent heavier by the end of the century than it is now, especially in the eastern United States. (See page 44 in the NOAA report to see the increases in very heavy precipitation rates from 1958 to 2007 by region.)

Heavier precipitation will be problematic for both drought and flood management, especially in the American West, according to a 2008 report by the Natural Resources Defense Council. Already, decreases in snowpack, less snowfall, earlier snow melt, more winter rain events, increased peak winter flows, and reduced summer flows have been documented throughout the region. It will become increasingly difficult to store water during high-flow or flood periods, and droughts are likely to become more severe. Accounting for this amplified strain on resources in a region already grappling with a burgeoning population and increased urbanization will be challenging. Climate models project continued increases in the heaviest downpours during this century, whereas the lightest precipitation will decrease.

Such difficulties will inevitably lead to more flooding nationwide, a pattern already apparent in the annual flood disaster declaration data. Floods incur high costs, such as the May-June 2008 Midwest floods that caused over $15 billion in damage, and the January 2009 floods in the Pacific Northwest that required evacuating 30,000 people, caused $125 million in damage and the shutdown of major roads and rail services. Flood-related damages have jumped from about $3 billion a year in the first half of the 20th century to an average over the last 2 decades of $6 to $8 billion a year (depending on whether Hurricane Katrina is included).

Other extreme weather events

Many types of extreme weather events, such as heat waves and regional droughts, have become more numerous and intense during the past 40 to 50 years. NOAA’s study outlines regional effects of climate change, including the fact that severe droughts are currently afflicting the southwestern United States and are projected to grow worse. The IPCC has also concluded that more intense and longer droughts have been observed over wider areas of the world since the 1970s.

There is no single comprehensive federal drought relief program. Funds can come from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Reclamation, US Army Corps of Engineers, and FEMA. Yet disaster relief from USDA alone has increased significantly over the past two decades. From 1985 to 2005, USDA paid over $26 billion in disaster damage payouts to farmers, with that number increasing over time by an average of $65 million per year. According to the Congressional Research Service, the federal subsidy to the crop insurance program for disaster relief has averaged about $3.3 billion per year since 2000, reflecting a large increase from an annual average of $1.1 billion in the 1990s and about $500 million in the 1980s. The 2008 Farm Bill authorized a $3.8 billion trust fund to cover the costs of agriculture disaster assistance over the next four years.

On top of legislated funding, Congress has provided ad hoc disaster assistance to farmers and ranchers with significant weather-related production losses in every crop year between 1988 and 2007. Such funding was utilized in the 2007 drought in the southeastern U.S., which caused $1.5 billion in damages. The 2006 drought in Texas cost over $4 billion, and the current “once-in-a-century” drought in Texas is “zeroing out” crops, forcing ranchers to liquidate their herds, and also eliminating summer recreation opportunities. Although total drought spending across agencies is not reported, scientists from NOAA and the IPCC are in agreement that droughts will become more intense and longer-lasting due to climate change, which means taxpayers will have to spend more money to help those affected by them.

Fortunately, Hurricane Claudette and the California wildfires have not caused enough damage compared to other recent storms or fires to warrant a presidential disaster declaration. But the growing number of presidential disaster declarations is another warning sign that global warming is already harming our people and economy. The Senate must promptly follow the House’s leadership by passing a clean-energy and global warming pollution reduction bill. Inaction or inadequate pollution reductions by the government would allow natural disasters in the United States to amplify in scale and frequency. This effect would present a clear and present danger to Americans. The Senate must act promptly and comprehensively to stem the greenhouse gas pollution that exacerbates global warming and its associated climate chaos.

Read about how the presidential disaster declarations process works.