Where the deals are.First came the news that anti-reformer Sen. Blanche Lincoln has taken over the Senate Agriculture Committee. Now, from the US Census Bureau we get even more bad news for those hoping for serious reform of our food system: the Census Bureau announced to day that middle class income is diving. Real median household income fell 3.6 percent between 2007 and 2008, from $52,163 to $50,303. As Felix Salmon of Reuters points out, that $1,800 drop is real money. Oh and I did I mention that the poverty rate is up, too?

Where the deals are.First came the news that anti-reformer Sen. Blanche Lincoln has taken over the Senate Agriculture Committee. Now, from the US Census Bureau we get even more bad news for those hoping for serious reform of our food system: the Census Bureau announced to day that middle class income is diving. Real median household income fell 3.6 percent between 2007 and 2008, from $52,163 to $50,303. As Felix Salmon of Reuters points out, that $1,800 drop is real money. Oh and I did I mention that the poverty rate is up, too?

Salmon also directed attention to David Leonhardt at the NYT who observed that “the typical American household made less money last year than the typical household made a full decade ago.” [Emphasis mine] And if you look more closely at the data, it now appears that most middle- and working-class Americans saw their inflation-adjusted incomes drop over the last ten years. American dream, indeed.

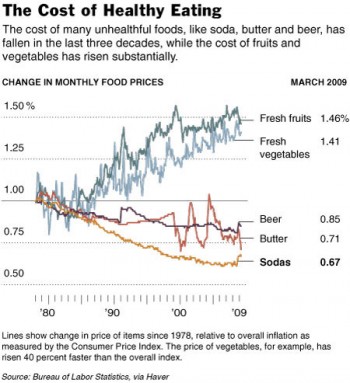

What does this have to do with food system reform? As both Tom Philpott and I have argued repeatedly: everything. With incomes and purchasing power dropping, families are drawn to the best deal on calories for the dollar, full stop. Sadly, as this NYT chart from a few months back indicates, this has meant highly processed foods and sweetened beverages at the expense of fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

Graph: New York TimesAt the same time and more perniciously, Big Food will invariably answer any calls to change its centralized, chemically-intensive, fossil-fueled and heavily processed system with threats of higher prices and unaffordable products. That was certainly its reaction to TIME Magazine’s recent article on the “The High Cost of Cheap Food” when, for example, Pork Magazine claimed that most Americans would be “priced out of Time’s idyllic food production scenario.”

Graph: New York TimesAt the same time and more perniciously, Big Food will invariably answer any calls to change its centralized, chemically-intensive, fossil-fueled and heavily processed system with threats of higher prices and unaffordable products. That was certainly its reaction to TIME Magazine’s recent article on the “The High Cost of Cheap Food” when, for example, Pork Magazine claimed that most Americans would be “priced out of Time’s idyllic food production scenario.”

It’s one thing to have to reorient food systems in the best of times. But when American’s see prices for the healthy food they’re supposed to be buying go up and up while their wages stay the same (or even drop), who can be surprised when the food movement’s priorities are rejected as elitist and optional.

But perhaps all is not lost. Michael Pollan in a NYT op-ed this week suggested that perhaps, with health care reform imminent, reformers may find themselves with a new ally — the health insurance industry. As Pollan says of the likely outcome of a reform bill:

Terms like “pre-existing conditions” and “underwriting” would vanish from the health insurance rulebook — and, when they do, the relationship between the health insurance industry and the food industry will undergo a sea change.

The moment these new rules take effect, health insurance companies will promptly discover they have a powerful interest in reducing rates of obesity and chronic diseases linked to diet. A patient with Type 2 diabetes incurs additional health care costs of more than $6,600 a year; over a lifetime, that can come to more than $400,000. Insurers will quickly figure out that every case of Type 2 diabetes they can prevent adds $400,000 to their bottom line. Suddenly, every can of soda or Happy Meal or chicken nugget on a school lunch menu will look like a threat to future profits.

When health insurers can no longer evade much of the cost of treating the collateral damage of the American diet, the movement to reform the food system — everything from farm policy to food marketing and school lunches — will acquire a powerful and wealthy ally, something it hasn’t really ever had before.

This sounds great. There’s only one problem. It’s probably not true. First, according to the Census Bureau’s recent announcement, almost 30% of Americans are already on government sponsored health care, i.e. Medicare, Medicaid and the VA. And second, the facts are that 1) much of the cost of diet-related diseases are already borne by the government since diet-related diseases tend to only get really expensive as you get older and go on Medicare and 2) Medicaid recipients, i.e. the poor, are likely to have the least healthy diets and suffer disproportionately from diet-related diseases. Plus, as it is, almost 60% of Americans get their coverage through their employer, which is to say it’s group coverage and thus pre-existing condition restrictions are more limited and, by definition, not underwritten.

It’s true that health care reform will give insurance companies more customers if Americans are required to buy coverage. But many of those will be healthy, former “free-riders.” The poor meanwhile will likely be covered under a Medicaid expansion, i.e. government insurance, not through private insurance — and they are the least healthy group that comes into the system. The health insurance companies have done an amazing job over the years insulating themselves from the cost of diet-related diseases — this round of health care reform likely won’t reverse that trend.

On top of that — the President’s comments notwithstanding — the government will revisit health care reform again and again. The insurance industry will have plenty on its lobbying plate as it fights for its life over the next few decades. Expecting them, as Pollan does, to “promptly get involved in the fight over the farm bill — which is to say, the industry will begin buying seats on those agriculture committees and demanding that the next bill be written with the interests of the public health more firmly in mind” is, I think, not realistic.

That said, Pollan is right that the industry has a role to play, though I suspect they already play it. He observed that health insurance companies are currently supporting NYC’s new anti-soda ad campaign. And this isn’t something to shrug at. Research has shown that, at least in the case of tobacco, anti-smoking media campaigns were effective. So it’s not unreasonable to expect that anti-junk food campaigns will work. But asking for Big Insurance to fight and win a legislative battle with agribusiness on industrial farmers’ home turf? Maybe not.

We undoubtedly need all of the food system reforms Pollan advocates in his op-ed. I just wouldn’t hold my breath waiting for the insurance industry to help enact them. The heavy lifting, I’m afraid, is all ours.