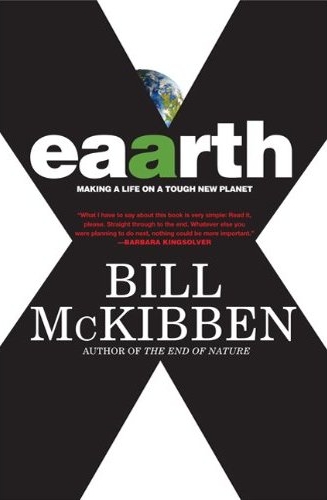

Bill McKibben’s new book Eaarth argues that our carbon pollution has already reshaped the planet enough that it deserves a new name. McKibben has been thinking hard about climate change for longer than almost anybody else, both as a writer and as an activist, and he doesn’t sugarcoat the situation. He stopped by Grist’s office in Seattle recently (he’s a board member) for a frank conversation about where the world stands and what we can do about it.

Bill McKibben’s new book Eaarth argues that our carbon pollution has already reshaped the planet enough that it deserves a new name. McKibben has been thinking hard about climate change for longer than almost anybody else, both as a writer and as an activist, and he doesn’t sugarcoat the situation. He stopped by Grist’s office in Seattle recently (he’s a board member) for a frank conversation about where the world stands and what we can do about it.

Q. You’ve been really busy over the last year organizing with 350.org. What led you to write a book during all that?

A. Well, theoretically I’m a writer. I wrote The End of Nature 21 years ago, and it was an early warning. There were a lot of warnings and nobody paid any attention. Now people need to understand that the “warning time” has passed. One of my reasons for writing was the sense I got beginning in the summer of 2007 with the rapid melt of the Arctic: All these scientists who had been worried and sober for a long time were basically panicked now. I wanted to try to get that across. So the first chapter of the book, about the most recent science, is a bit of a two-by-four upside the head. Even many of the scientists working on this stuff don’t know it all because they come from such different disciplines: The ocean guys don’t know just how tough it is in the glaciers. The glaciologists aren’t quite up to date with what’s going on with storms.

The last two-thirds of the book are much more speculative. If we have a new planet, how do we live on it successfully? Instead of the list of the six things you should do to improve your greenness, it’s an attempt to intellectually grapple with that. The key environmental question we face seems to be: How do we make extremely large transitions? What does that look like?

Q. I wish we could find an example where we made such a dramatic transformation. This winter I was reading about the Civil War and the type of dramatic change that happened over 15 years. But the challenge is we don’t really have those 15 or 20 years.

A. I think this is a considerably bigger event than that, because the thing we’re transitioning from is the thing that underwrote modernity—fossil fuel. That’s why the world looks the way it does in almost every aspect of the Western world. So, transitioning from that to what comes next is, at some level, an impersonal task. Certain things have to happen for us to get started, and the one that everyone can name and understand is getting the [carbon] price right. That’s one of the few levers large enough to begin exerting influence.

Q. It makes intellectual sense but, viscerally, it’s just a hard thing for people to relate to.

A. Prices are hard to relate to? All you have to do is remind people of the summer of 2008. What happened when the price of gas went to $4 a gallon in your town? Everybody quickly figured out they didn’t need a military vehicle to go to the grocery store.

Q. You’re pretty critical about economic growth in the book and I thought that was pretty radical. How has that been received?

A. The fact that it seems so radical is testament to how deeply ingrained this idea that growth solves every problem is in our thinking and our political structure. But it’s not something that people have believed forever. Economic growth, as an idea, is essentially a mid-20th century invention in the wake of the Depression.

The radical breach with human history has been the last 70 years. When the Arctic melts, that’s a pretty good sign that you’re running into fundamental limits. And the measure of the depth of our obsession with the economy and growth is that the melting Arctic seems less catastrophic to us than this temporary recession we’ve stumbled into.

Think of the language our politicians use: “The economy is ailing.” “It’s hit a rough patch.” Or “it’s healing.” Or “showing signs of healing.” I mean, we talk about it like you would your great aunt. But with the planet, it’s “natural cycles” and “pay no attention.” “The Arctic melted: must be a natural cycle someplace.” Too many people now live believing that the economy is something real, as opposed to an abstraction that exists within the natural world, and not the other way around.

Q. So what will the future look like? Do the communities we need to build look like Vermont and the local agrarianism you write about, or like Portland and sustainable urbanism?

Q. So what will the future look like? Do the communities we need to build look like Vermont and the local agrarianism you write about, or like Portland and sustainable urbanism?

A. Anybody who has some absolute master plan of what the world is supposed to look like at the other end is an idiot. All we can do is affect trajectories: try to bend the way we’re going in one way or another and then see what happens.

My guess is that the availability of cheap fossil fuel everywhere has a homogenizing effect. Logic has led us to adopt the same few patterns over and over and over again in all kinds of places. If we move beyond that and begin dealing with much more indigenous energy resources in places all over the planet, my guess is the effect will be much less homogenous. People in a million different places will figure out a million different ways to deal with the world around them, because they’ll be dealing with the sun that falls on their place and the wind that blows by it or how much rain they get, what the cultural norms are and how dense their population is, and a thousand other variables that lead you in a lot of different directions. So neither Vermont nor Portland, except in Vermont and Portland.

Q. You write quite a bit about food systems in the book.

A. The food stuff is very interesting, and energy follows the same pattern: The farmers market became our metaphor for how to think creatively about food in this country, so, in essence, we need a farmers market in energy. I’ve got solar panels on my roof. I’m a utility. I’m firing it down the grid. It’s not going to completely replace large-scale energy. We’re still going to need some big windmills out in the Dakotas and concentrated solar power plants in the desert. But we can produce an awful lot of what we need close to home with good results. The metaphor for all of this, the thing that allows us to think more productively about it, is the internet. Its sudden appearance in our lives 15 years ago has been interesting for many reasons, including the provision of a new metaphor, almost, for thinking about the world. It’s the opposite of what used to be. Instead of a few centralized information sources broadcasting things out to us, now we have this insanely multi-modal farmers market of information. Everybody brings some in and everybody takes some out. Hence, it has great resilience. It’s not brittle in the way that any centralized operation is. To me it’s the great wild card we’ve got.

Q. It sounds like that shaped the way you structured 350.

A. It’s precisely the reason we organized Step it Up and 350 the way we did. When we started doing Step it Up, people said we should have a march on Washington. No. Think about it for a minute: It’s dumb to have people drive across America to protest climate change. And in the world where we now live, we can hold events in every congressional district in the country and knit them together and have it make noise. We had very little in the way of resources and organization, but we had way more people than you can fit on the National Mall. [On Oct. 24, the International Day of Climate Action,] we managed to pull off 5,200 simultaneous demonstrations in 181 countries. We owned Google News for about 36 hours. It was far and away the biggest story in the world. It was that way precisely because it was going on everywhere all at once. Every newspaper was running a big picture of what went on in their town and linking to the AP story. Every TV station had the feed from Reuters or whatever and their local story.

Q. You’ve touched a little bit on your own thinking about being realistic, even despairing, versus finding hope. When you work with young people, where do find they are on that continuum?

A. I find the people who get all upset and creeped out and can’t deal with stuff tend not to be young people. At least at the moment, college-age kids strike me as highly realistic. I think they have a pretty good sense that choices are increasingly constrained. They’re grateful for people saying that straightforwardly.

The big problem is that we’ve never had a movement about climate change. We’ve had a zillion different projects, but they’ve never coalesced into a movement. I think we badly need that. One of the effects of building it is it bucks people up. There are good things about being part of a movement, including that you feel the strength of the people around you.

Last October, we took over Times Square and showed thousands of pictures that people around the world sent. We were uploading them directly as they came in under those jumbo advertising signs, partly because we wanted to show New York what was going on, and it was good for media. But we were also taking pictures as we did that, of each one of them as they went up, and emailing those back out to a bunch of kids in the Congo: Here’s what you look like 50 feet tall in Times Square. They need to feel powerful, and they should feel powerful, because as part of a big international movement they are powerful.