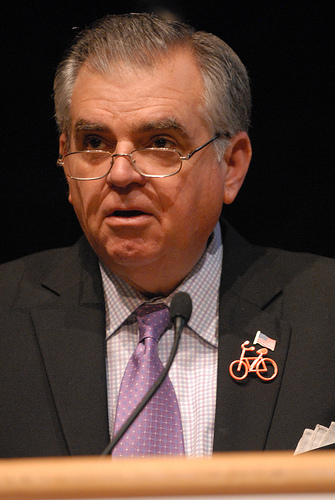

Bike PortlandU.S. DOT Secretary Ray LaHood isn’t afraid to show some bike love

When Ray LaHood was nominated by President Obama to be the Secretary of the Department of Transportation (DOT), it seemed like an afterthought. The selection of LaHood, a Republican Congressman from Illinois with a reputation for political pragmatism, was seen by many as a gesture at bipartisanship that indicated just how little the administration cared about possible innovations at the DOT.

Over at Worldchanging, Alex Steffen called the appointment “a profoundly uninspiring vote for business as usual,” and at Streetsblog, where I worked at the time, Aaron Naparstek wrote this:

The selection of a downstate Illinois Republican with close ties to highway lobby stalwart Caterpillar Inc. is being taken by many as a clear sign that progressive transportation policy is, for now, nowhere near the top of the Obama’s agenda.

What a difference 20 months makes.

LaHood has proven to be much more than a roads-and-bridges secretary. He’s been an outspoken and articulate proponent of high-speed rail. He’s mounted an aggressive campaign against distracted driving. He’s jumped up on a table to address the National Bike Summit, saying that, “I really came here just to say thank you to all of you for hanging in there with us. You all have made a big difference.”

And perhaps most significantly, he has emerged as a defender of the “livable communities” concept, advocating for the construction of a transportation infrastructure that would make walking, biking, and modern public transit available — and attractive — options for every American.

Reform of the nation’s transportation system is still stalled out at the congressional level, with the reauthorization of transportation funding legislation now running more than a year behind schedule. There’s widespread Republican opposition to Obama’s $50 billion infrastructure spending proposal.

But LaHood, who has a jovial, guy-next-door demeanor, is still upbeat. We had a chance to talk with him by phone the other day about what exactly “livable communities” are — and if Republican legislators will ever vote to fund them.

Q. So tell me, what does this concept of “livability” really mean?

A. This is something I’ve never really talked about, but growing up, I lived on the east side of Peoria. When I was growing up, I could walk to my grade school. We had one car, but we would bike everywhere we went. We could walk to the grocery store. In those days, we had streetcars and buses, which people used to get to downtown Peoria, which was probably five miles from my house. I used to take a bus to my dad’s business. I grew up in an era [of] livable neighborhoods and livable communities — what we’re really trying to offer to people around America. When there was no urban sprawl, when you didn’t have to have three cars, when there weren’t houses with three-car garages, everybody had one car.

That era was lost on a generation that decided they wanted to build big malls and have cities expand in a way that didn’t really reflect the ideas of livability.

When I came to this job, I thought about it in that context, but also in the context of a city like Washington, D.C., or Chicago, where you can live without a car. Where, on the weekends, my wife and I can take our bikes, and if we want to go all the way to West Virginia on our bikes from Georgetown, we can do that. If we just want to go to Bethesda, we can. If we want to go for a walk, we can. This is a city where you can live without a car and get to airports, get to your job, get to the grocery store, and it’s the kind of community that offers people many different transportation options and amenities that I think have been lost in other cities.

So, as we travelled the country the last 20 months, visiting more than 90 cities in 40 states, what we found was that there’s a pent-up demand in America for more walking paths, biking paths, more transit, more buses. I just helped inaugurate a streetcar program in Atlanta. I’ve been to New Orleans, where they want to expand their streetcar system. I’ve been to Portland. On the day that I was going to the streetcar inauguration in Portland, I saw over 200 people at 7:30 in the morning riding their bikes to work. I’ve seen what’s happened here in Washington with walking and biking paths, the biking avenues or lanes that have been created along Pennsylvania Avenue, along 14th street and 16th street.

It’s what Americans want.

Q. But politically, it’s been a little bit of a tough sell. There are a lot of people, especially on the Republican side of the aisle, who seem to think that encouraging density and more walkable communities is, in effect, forcing people to live in the kinds of places that they don’t want to live in.

A. I think when politicians begin to listen to their constituents, what they find is that their constituents are way ahead of them on livability and sustainability, on having cleaner, greener communities, on having walking and biking paths, on having streetcar systems. I think when politicians who are elected by the people begin to listen to their constituents, they begin to get with this kind of livable, sustainable community program.

Q. Do you think in the current political climate, there are a certain number of people in Congress who are just invested in opposing whatever the president comes up with?

A. I think there are some traditional people in Congress who like the idea that we continue to build roads and bridges and things like that. I think we’ve sent a pretty loud message that one of our signature transportation programs will be livable and sustainable communities. One of our signature transportation programs will be connecting America with high-speed intercity rail, so people can get out of their cars. They can take a train ride to see Grandma rather than doing it in a car.

I just think these are signature programs now. They’re not going to go away, not because of Ray LaHood or because of Barack Obama, but because this is what people want. Once politicians begin to learn that, they begin to adopt the idea that these are good opportunities for their constituents and for Americans.

Q. When we do get to the reauthorization of transportation funding, what do you think that’s going to result in? Do you think that there is going to be a change in the funding formulas?

A. I think you will see a sizable chunk of money for livable, sustainable communit

ies. I think you will see reform of MPOs, the metropolitan planning organizations, so they incorporate more of communities and more stakeholders. I think you’re going to see one of the signature programs will be high-speed intercity rail that ultimately will connect America in the next 25 years, or at least 80 percent of America. More emphasis on streetcars and other transit options for people, because this is what Americans want. This is the direction we’re going.

We had over a two-hour meeting with [Transportation and Infrastructure Committee] Chairman [Jim] Oberstar [D-Minn.] on all of our signature programs, and there’s not a nickel’s worth of difference from what we want and what he wants. We’re always going to build road and bridges, and we have a state-of-the-art interstate system. But people want more than that now.

Q. Do you think that suburbs and cities have competing interests, or do you think that their interests are complementary? How can you talk to people about how those interests are complementary, and not just have it be this thing where suburbs are pitted against cities?

A. I think walking and biking paths provide the connectivity for cities and suburbs. In my hometown, Peoria, I told you what it was like back in the ’50s and ’60s when I was growing up, as a boy. They just have gotten the rights to a rail line called the Rock Island Line. Right now it’s a 26-mile walking and biking path. They’ve just now purchased the rights to the rest of the rail. They’ve just torn up all of the rail, and they will connect several communities, both suburban and rural. I think these walking and biking paths, are the pathways, if you’ll pardon the pun, to connect urban and rural and suburbia.

I think another way to do it is through good transit programs, where you have transit programs in cities that also provide service to the rural and suburban area. Again, in my hometown, they’re building a huge VA clinic in suburbia, which was once in the downtown area. The only way they got away with doing that is that the transit system said, we will have regular service in order to deliver veterans who need transportation services. That’s the kind of connectivity — so you can get to a VA clinic if you don’t have a car or access to a car, that you can ride your bike from a downtown area all the way out to suburbia or to a rural area. That if you live in a rural area, you can get to a grocery store or your doctor’s appointment or hospital, because the transit system will provide those services. That’s the kind of connectivity that I think people want, and that we’re really thinking about.

Q. What have you learned in this process about what Americans want? Have there been any surprises?

A. I’ve been in public service for 30 years, as a staffer for 17, then as a member of the House for 14, and now I’ve been in this job 20 months. In a job like this, you can make a difference. The one thing that I have going for me is that President Obama supports all of these activities. He really has given us the opportunity to develop some significant, signature programs that have never been considered or highlighted by DOT.

I think people have always thought of the Department of Transportation as the department that builds roads and bridges. But you can do big things, and dream big dreams, and the president has really given us the opportunity to do that. You can think outside of the box. We’ve been thinking outside of the box. I didn’t realize that we’d really be able to do that.