In the final year of his remarkable life, Robert C. Byrd, the longest serving senator in U.S. history, did one more remarkable thing. He called for serious dialogue on coal, climate change, and the effects of mountaintop removal mining.

“To deny the mounting science of climate change is to stick our heads in the sand and say ‘deal me out,'” Byrd told his fellow West Virginians late in 2009. And on the EPA’s efforts to rein in the most egregious damage from mountaintop removal, he said, “West Virginians may demonstrate anger towards the EPA … but we risk the very probable consequence of shouting ourselves out of any productive dialogue.”

Briefly, there was hope that the mountain state’s elder statesman might pull local politics away from a dead-end logic. Very briefly.

“I’ll shoot it if I have to!”Sen. Byrd died in June. By October, the man who would replace him in the Senate thumbed his nose at Byrd’s desire for reasoned discourse and picked up a gun.

“I’ll shoot it if I have to!”Sen. Byrd died in June. By October, the man who would replace him in the Senate thumbed his nose at Byrd’s desire for reasoned discourse and picked up a gun.

Joe Manchin, West Virginia’s two-term governor and now senator-elect, loads the chamber of a hunting rifle in his now famous campaign ad. He pledges to get the EPA bureaucrats “off our backs” and then shoots a hole through a mock copy of a “cap-and–trade” bill. To those of us who have anxiously watched tensions increase in the state’s southern coal counties, this seemed a risky escalation of violent rhetoric. But it helped Manchin win the endorsement of the state’s coal association. He ran hard to the pro-coal right to fend off a surprisingly strong challenge from Republican millionaire John Raese. Raese’s campaign sounded like a wistful yearning for the yesteryear of laissez faire capitalism and zero industry regulation. You know, the good old days of Farmington and Monongah and Buffalo Creek, when mining disasters claimed lives by the scores.

This April we saw the tragic return of events of that scale. The explosion at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch Mine killed 29, the worst mining disaster in 40 years. It was a sobering reminder of the role of safety regulation and just how weak the main regulator, the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration, has become.

After seeing Upper Big Branch, after seeing Sago, after seeing huge chunks of landscape reduced to rubble, you might think West Virginia political leaders would respond with some serious consideration of the role of regulation in safety and environmental protection. You might think the politicians who eulogized Byrd in the summer might actually have listened to the man’s last message.

Alas, Charleston Gazette reporter Ken Ward Jr., the best on the coal beat, told me ,“In West Virginia I think you no longer have anybody who is a major elected official or major political figure who is really interested in confronting these issues in a meaningful way.”

Witness the contest for West Virginia’s third congressional district, home to most of the state’s mountaintop removal mining, the Upper Big Branch disaster and some of the most disheartening socioeconomic indicators in the nation.

There, state Supreme Court Justice Elliott “Spike” Maynard was the Republican challenger to West Virginia’s long-serving Rep. Nick Rahall, who chairs the House Natural Resources committee. Maynard tried to paint Rahall as part of “Obama’s war on coal” because, well, he had a “D” by his name. Rahall responded by bragging that he was the one blocking even committee level consideration of a bill that would limit mountaintop removal.

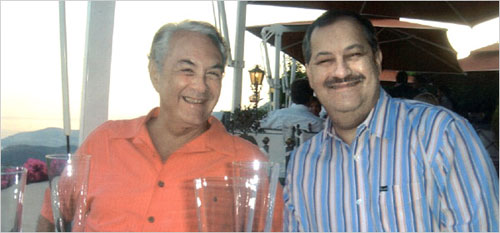

The Charleston Gazette (Ken Ward Jr.’s Coal Tattoo blog)Maynard’s attacks might have worked in this political climate if not for a few of his vacation pictures. There was Spike in the French Riviera, grinning alongside Don Blankenship. Blankenship is CEO of Massey Energy, whose safety practices are under investigation for the Upper Big Branch disaster. At the time of Don and Spike’s Riviera getaway, Massey had a high profile case pending before the state supreme court.

The Charleston Gazette (Ken Ward Jr.’s Coal Tattoo blog)Maynard’s attacks might have worked in this political climate if not for a few of his vacation pictures. There was Spike in the French Riviera, grinning alongside Don Blankenship. Blankenship is CEO of Massey Energy, whose safety practices are under investigation for the Upper Big Branch disaster. At the time of Don and Spike’s Riviera getaway, Massey had a high profile case pending before the state supreme court.

Rahall won, but will lose his committee leadership as the House switches to Republican control.

Campaign finance records show the coal industry was on track to pump more than $3 million into the campaigns of federal candidates this election cycle, on top of the $24 million it spent lobbying the last Congress.

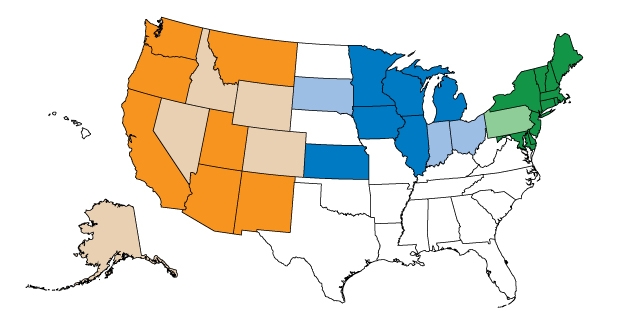

The industry wants to blunt likely efforts to regulate coal ash disposal, mercury emissions and tighter controls on traditional air pollutants from power plants. But the biggest battle will be the one over EPA’s authority to regulate CO2. Now that climate legislation is dead, EPA’s ability to use the Clean Air Act is one of the few tools left to rein in greenhouse gases. Expect Democrats from West Virginia and the rest of coal country, the oil patch and industrial Midwest to join Republicans in the effort to block any such action from EPA.

Once again, it is instructive to look at the late Byrd. One of his last votes was on this very question. Alaska Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski’s resolution challenged EPA’s finding that greenhouse gas emissions endanger the public.

“This,“ the senator said, “is like voting to assert that there is no climate change or global warming going on, and to dismiss scientific facts.” He voted “No.”

Joe Manchin will soon take Byrd’s seat. Nick Rahall will return for an 18th term in Congress. West Virginia will still be a bit of blue on electoral maps. But party matters little when it comes to the region’s most important questions. I recall standing on a ridge targeted by mountaintop removal this fall, talking to an activist who said, “We’re in a coal-acracy, ruled by a bunch of coal-a-crats.”

Joe Manchin will soon take Byrd’s seat. Nick Rahall will return for an 18th term in Congress. West Virginia will still be a bit of blue on electoral maps. But party matters little when it comes to the region’s most important questions. I recall standing on a ridge targeted by mountaintop removal this fall, talking to an activist who said, “We’re in a coal-acracy, ruled by a bunch of coal-a-crats.”

Regardless of the election, there’s no question who’s king.