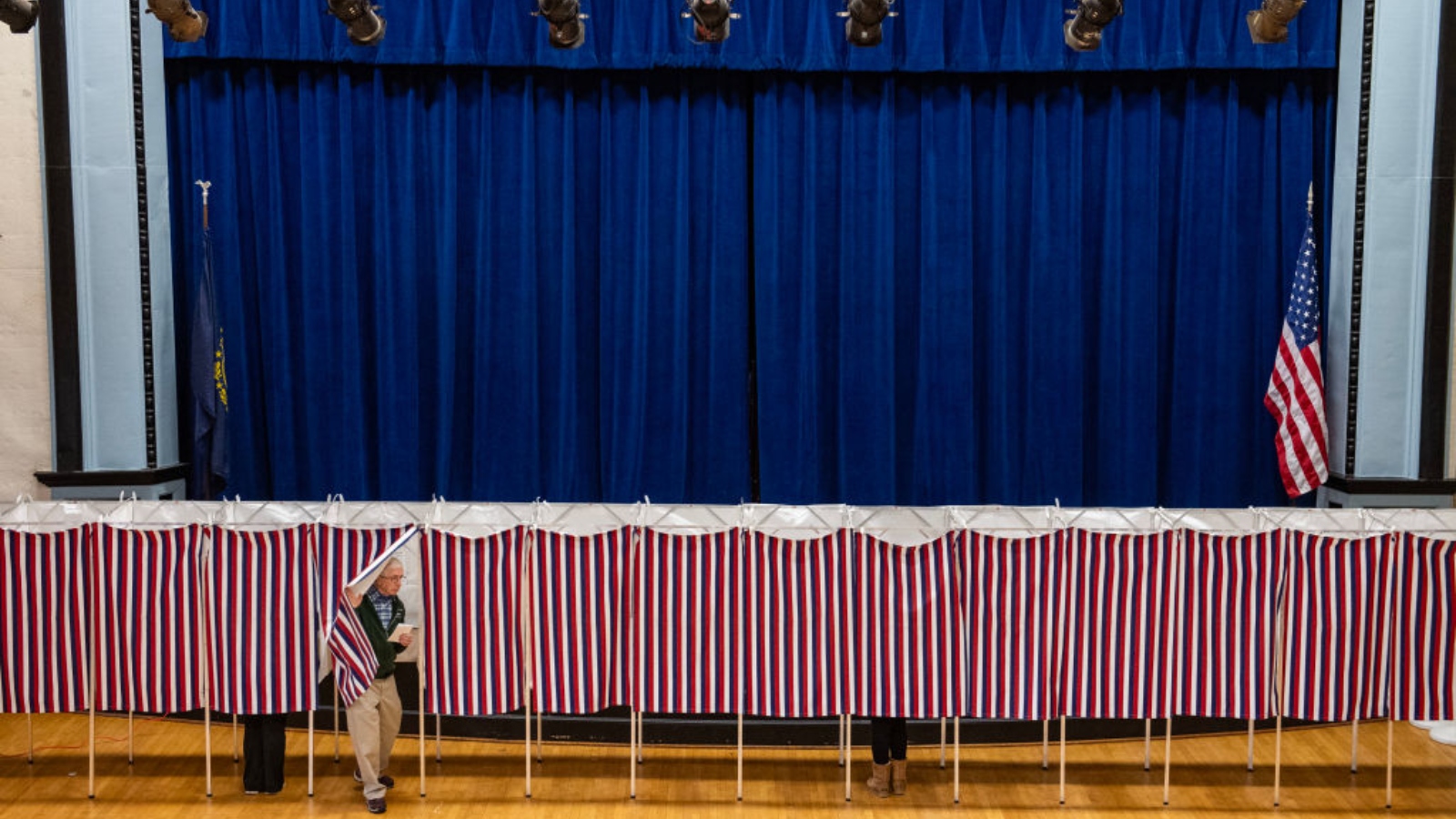

Election Day in Lake Charles, Louisiana began with heavy rain and tornado warnings. Belts of precipitation traveling up from the Gulf of Mexico hammered the city in the early morning hours, and let up by the early afternoon. At polling locations across the city, voters stepped over deep puddles and soggy soil to cast their ballots. The storm was nothing new in this corner of southwest Louisiana, a mostly conservative region in a Republican-controlled state, where residents have borne the brunt of the hurricanes that have passed through over the past four years. Polls in the state will close at 8 p.m. local time, and voters should know the unofficial results by 11 a.m. tomorrow morning — whether the state’s eight electoral college votes will go to Kamala Harris or Donald Trump.

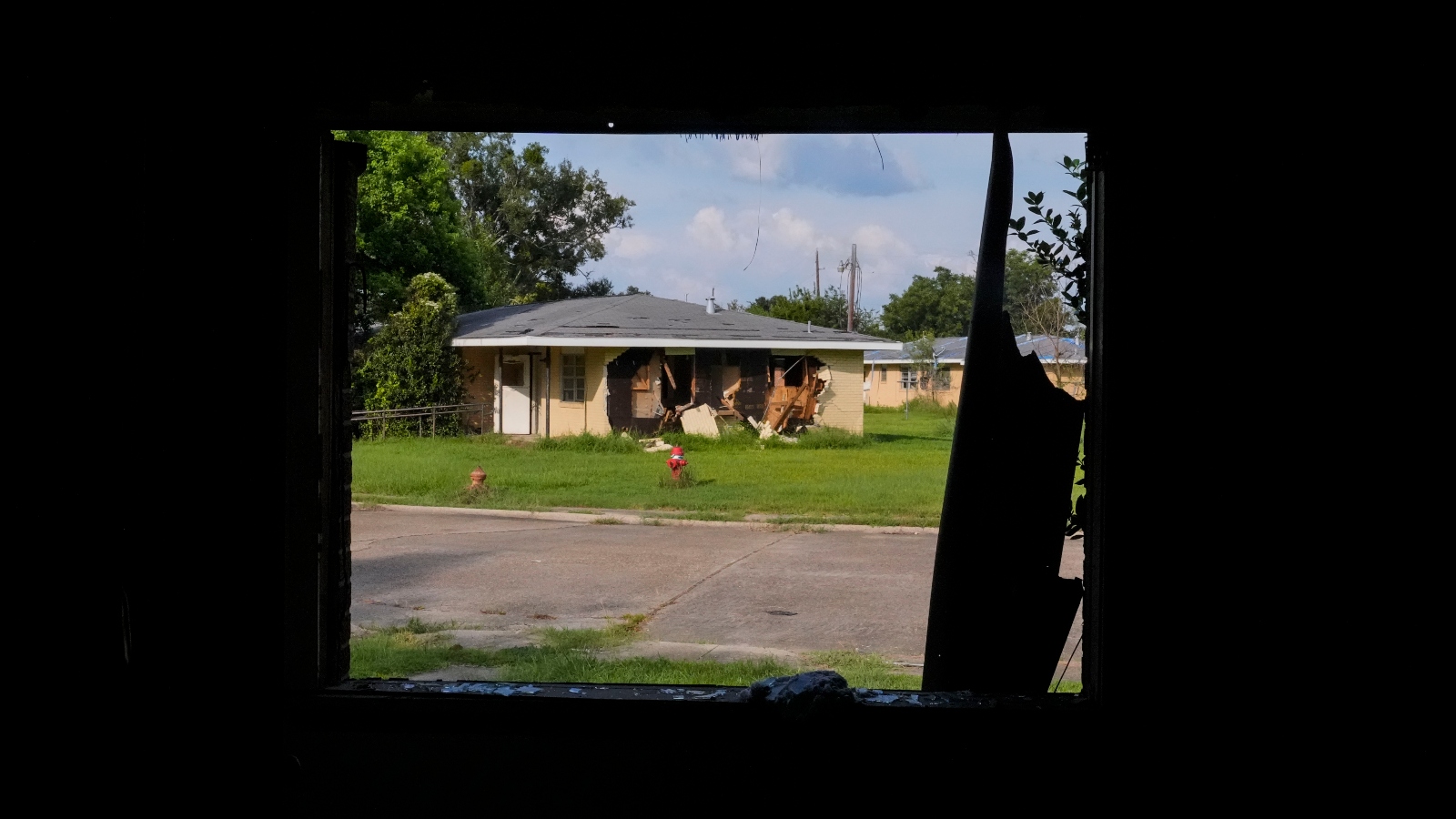

“I’m still displaced,” said Stephanie Edwards, a mother of two whose home was destroyed during Hurricane Laura, which barreled through the state in late August of 2020, causing $17.5 billion in damage. In the aftermath, “I didn’t see anybody but regular people come down to help.” Speaking from behind the counter of the Exxon Mobil gas station where she works as a cashier, Edwards told Grist that the Biden Administration had done little to improve the lives of people like her, who lost everything in recent hurricanes. The Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, she said, offered her just $2,400 in disaster relief funds — hardly enough for two months’ rent. (President Biden was sworn into office about five months after Laura.) Edwards ended up moving back in with her mother. Her disappointment with the government’s response was one of the reasons she decided that Donald Trump earned her vote.

“I just feel that Trump is a better option for us for the simple fact that he cares about the American people,” she said to the nods of her coworker, Sherri. “He cares about our environment. He cares about what’s going on in the United States.”

Edwards said that she disagreed with Biden’s decision to “shut down the oil fields,” but that she was not opposed to his incentives for more green energy production. (Despite promises to limit oil and gas drilling on public lands, Biden has overseen a record boom in fossil fuel production).

The oil and gas industry is central to the economy of southwest Louisiana. Over the past decade, new pipelines have been built to carry natural gas from Texas through Lake Charles and down into Cameron Parish, where fossil fuel companies are scrambling, after a Louisiana judge blocked Biden’s pause on new permits for exporting natural gas, to erect liquified gas terminals to export American fuel abroad. Petrochemical companies like Sasol and Westlake Chemical are expanding their industrial operations across the Calcasieu River in the town of Westlake, already a maze of flare stacks and chemical storage tanks pressed up against the majority-Black community of Mossville.

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

Speaking from the parking lot of Ray D. Molo Middle School after casting her vote, Erica Dantley told Grist that she was concerned about the possibility of future chemical plant explosions in the area. The rubber manufacturing facility near her house caused unpleasant odors sometimes, but it’s the new gas pipelines and the large petrochemical plants across the water in Westlake that she’s really worried about. “If they explode or leak, or whatever, that pollution will come this way,” she said, referring to the explosion at Biolab’s facility in 2020 and another at Westlake Chemical’s south plant in 2022. Both Dantley and her daughter, Kailynn, 18 and excited to be voting for the first time, told Grist that they believed a Harris administration would take more seriously the pollution risks borne by communities like theirs, and work to enforce the environmental regulations established over the past four years.

“We need to keep the progress going,” Dantley said.

Like everyone else Grist interviewed, Carol Taylor’s life has been shaped by successive hurricane seasons. She recalled putting as much as she could fit in her Ford Ranger as Hurricane Rita closed in during the fall of 2005. Her house in Cameron Parish was badly damaged in the storm, and then bulldozed by the Army Corps of Engineers without her permission. Fifteen years later, after she’d moved to Lake Charles, she fared better through Hurricanes Laura and Delta, only needing a new roof for her house. Despite the outsized impact that natural disasters have had on her life, Taylor said that climate policy didn’t factor heavily in her voting decision, though “it probably should.” She was more concerned about women’s access to abortion, an issue that she and her adult children diverged on.

Asked whether she supported a transition to renewable energy, which would wean the economy off of the stuff feeding the growth of Lake Charles’ economy, Taylor replied, “I just know that something has to change.”

She continued saying, “Even if everything goes green, it’s gonna take years for everything to finally get switched over, right? There has to be a happy medium in there somewhere.” Then she shrugged.