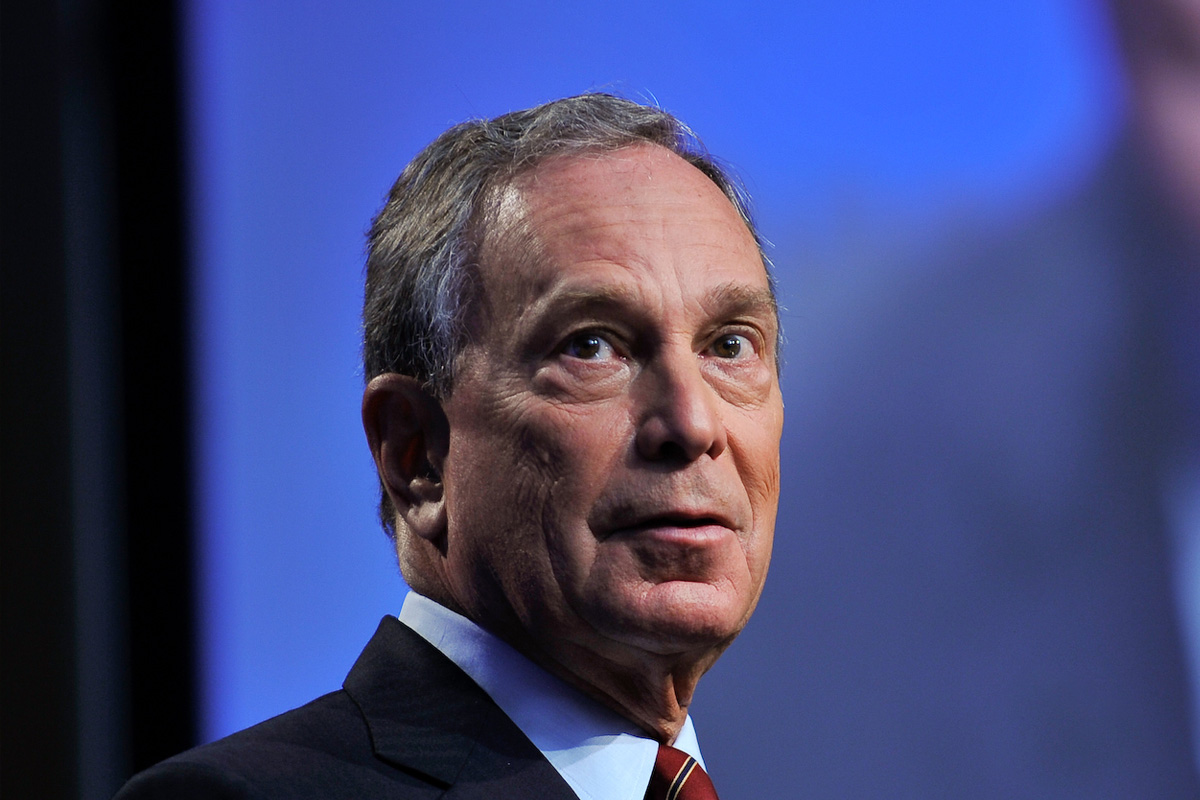

Former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg is going to spend over $10 million on TV commercials targeting swing state attorneys general who are suing to overturn the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan. The ads will run in Missouri, Florida, Michigan, and Wisconsin, targeting three Republicans and one Democrat (Missouri’s Chris Koster).

Bloomberg, a multibillionaire who dramatically outspent his opponents with record-breaking sums on his way to New York’s City Hall, has demonstrated a willingness to spend heavily, but wisely, to advance his political agenda. The sample ad posted by The New York Times, criticizing Koster, is cleverly framed to transform climate change — an abstract, low-priority issue for most swing voters — into both an everyday problem and a synecdoche for broader concern about corporate capture of politicians. It notes Koster’s “hundreds of thousands of dollars” in campaign donations from “polluters.” “He wants polluters to be free to pump billions of tons of carbon into the air, contributing to asthma and heart disease,” the narrator concludes. “Chris Koster puts polluters ahead of Missouri families.”

This is smart politics for climate hawks. Clear majorities of the public, nationally and in swing states, support climate action in general and EPA regulation of carbon emissions in particular. Attorneys general are relatively obscure figures to their state’s voters, and their actions are often little-noticed. But by signing on to sue the EPA to block its biggest effort to combat climate change, they are going against public sentiment and risking re-election — if, that is, anyone pays attention. Bloomberg is trying to make sure they do.

Missouri may not be his best test case. It’s a more Republican-leaning state than the others, with a foot in the South. Its energy portfolio is heavily dependent on coal. But Koster is a Democrat, running for governor, and while the suit may not hurt him in the general election, it probably will in the primaries.

While Missouri may not prove to be fertile ground for pro-environment attack ads, Florida very well might. Two Florida Republicans who oppose the Clean Power Plan, former Gov. Jeb Bush and Sen. Marco Rubio, are running for president. But Florida is a state with a generally pro-environment electorate. It’s not a big fossil fuel producer, and it is heavily dependent on attract tourists, retirees, and second-home owners. They’re not moving there for, say, the great avant-garde theater or Asian cuisine; they’re coming for the weather, beaches, and outdoor recreation.

So climate change and air pollution pose extremely stark threats to Florida’s population and economy. South Florida is almost entirely at or near sea level, on top of porous limestone. It is frequently battered by hurricanes and the rising Atlantic Ocean is already beginning to engulf it.

Historically, Florida Republicans have been more moderate on the environment than on other issues. Bush broke with his brother’s administration to oppose offshore drilling. Former Republican Gov. Charlie Crist stopped new coal plants from being built, set new energy efficiency standards for state buildings, and made a deal with U.S. Sugar to protect a giant swath of the Everglades wetlands. His successor, Gov. Rick Scott (R), has been much worse on environmental issues, especially climate change. He banned state agencies from discussing climate change, cut funding for water protection and land conservation, and stopped enforcing state environmental regulations. That came to be a political liability for him, as his pathetic “I’m not a scientist” line on climate science was met with derision and an offer from climate scientists in Florida to meet with him and educate him. Scott took the meeting, but didn’t change his position.

To soften those criticisms, Scott has tried greenwashing. In June, he falsely claimed that his administration has devoted “record funding” to the environment. “What the Republicans have learned over the past generation in Florida is that there’s nothing to be gained from being anti-environment,” says Rep. Alan Grayson, a Florida Democrat who is running for Senate. “The Republican agenda in Florida is the Chamber of Commerce agenda. With minor exceptions there’s no overlap between what the Chamber wants and what the environmentalists don’t want. So Jeb pretended to be an environmentalist.”

But now that their right-wing base is empowered, and more conservative, ideological Republicans like Rubio, Scott, and Attorney General Pam Bondi are winning their party’s nomination for statewide office, Florida Republicans are showing their true colors — and they aren’t green. Bush and Rubio do not fully accept the science of climate change and both of them oppose climate action. Bondi dismissed a question last month on whether climate change is human-made with the nonsense response, “I’m not going to get into a philosophical discussion with you about climate change.” Perhaps that’s the new iteration of “I’m not a scientist,” though it’s even stupider: Climate change is a scientific, not philosophical, phenomenon. As the state GOP has moved rightward, moderate, pro-environment Republicans have been pushed out. Crist was defeated in the 2010 Senate primary by Rubio and ran unsuccessfully in 2014 for governor as a Democrat.

Reactionary stances on climate change are a political liability for Republicans — especially in a hot, muggy, coastal states such as Florida — that climate hawks should exploit. And why limit it to attorneys general? Senators such as Rubio should also be targeted. Republican members of Congress from these states who want to appear moderate on climate change, like Florida’s Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, should also be publicly pressured to state that they won’t vote for GOP bills to repeal or defund the Clean Power Plan. So should Democrats who have voted against the plan.

Climate regulations face a torrent of outside spending from fossil fuels, energy utilities, and other business interests. Deep-pocketed climate hawks like Bloomberg and Tom Steyer can help level that playing field.